ALMA's sharpest photo suggests Fomalhaut star's warped ring was sculpted by 'yet-to-be-seen' ancient planets

A recent study of the Fomalhaut star system has revealed a new clue in the long-standing mystery of its highly unusual debris disk. Using new, high-resolution images from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have discovered that the star's immense ring of dust and debris is not only misshapen, but its eccentricity, or degree of lopsidedness, changes with distance from the star. This discovery suggests the presence of unseen planets that are gravitationally sculpting the disk, as per NRAO.

The research, detailed in two papers published in The Astrophysical Journal and The Astrophysical Journal Letters, was led by a team from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and Johns Hopkins University. For nearly two decades, astronomers have been puzzled by the eccentric shape of Fomalhaut's debris disk, a vast ring of rocky material similar to our own solar system’s asteroid belt. Previous models assumed the disk had a uniform shape, but the new data show this is not the case. The ring’s shape becomes steadily less stretched the farther a segment is from the star, a unique feature known as a negative eccentricity gradient.

📡💍"Fomalhaut star's warped ring shows evidence of sculpting by ancient planets" by @physorg_com https://t.co/OM4n6bQDJJ pic.twitter.com/4bFNFjREms

— ALMA Observatory📡 (@almaobs) September 6, 2025

According to lead author Joshua Bennett Lovell, a Submillimeter Array Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, this is the first time such a phenomenon has been conclusively shown in any debris disk. The team’s new model, which accounts for the disk's complex structure and asymmetries, points to a steep decline in eccentricity, a finding predicted by theories of how planets influence debris disks.

This new evidence suggests that a massive, yet-to-be-seen planet orbiting Fomalhaut may be responsible for the disk's peculiar structure. The researchers believe the planet could have shaped the disk early in the system's history, and its gravitational pull has maintained the ring’s warped form for more than 400 million years. Jay Chittidi, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, explained that older models with a fixed eccentricity could not fully explain the features seen in both ALMA and previous James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) data. "We are now able to better interpret this disk and reconstruct the history and present state of this dynamic system," he stated.

The research team hopes that further observations, which have already been approved, will help pinpoint the location of the hidden planet. In the meantime, they have made their eccentricity model code public so other astronomers can apply it to similar star systems.

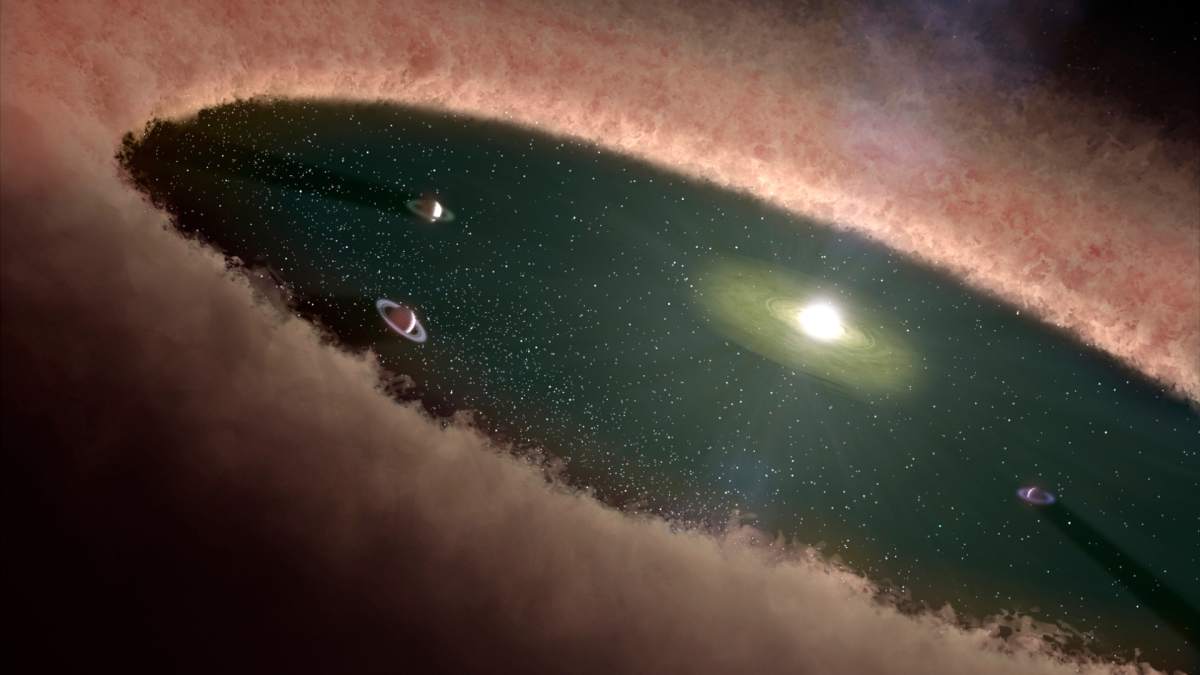

This isn't the first time ALMA has provided a new perspective on planetary systems. Another international team of scientists recently published research in the Astrophysical Journal Letters that challenges long-held ideas about how planets form. Using ALMA, they found compelling evidence that protoplanetary disks, the dusty, gaseous birthplaces of planets, are often subtly warped.

These disks, once thought to be perfectly flat, show slight bends and twists that are only a few degrees in their inclination. This subtle warping, which resembles the slight tilts of planets in our solar system, suggests that the initial conditions of planet formation are far less orderly than previously assumed. Confirming this finding could significantly alter our understanding of how planets grow and settle into their final orbits.

More on Starlust

Protoplanetary disks are not so flat after all, suggests compelling evidence from ALMA

Webb Telescope discovers mysterious CO₂-rich disk with no water around a young star