Radio observatories detect hidden gas shielding record-breaking space blast

With a network of high-powered radio telescopes, scientists have discovered a giant "cocoon" of gas surrounding one of the most explosive events ever recorded in space. This cocoon was making one of the brightest events in the universe appear to be missing key chemical signatures, according to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

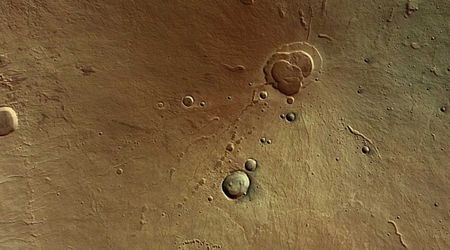

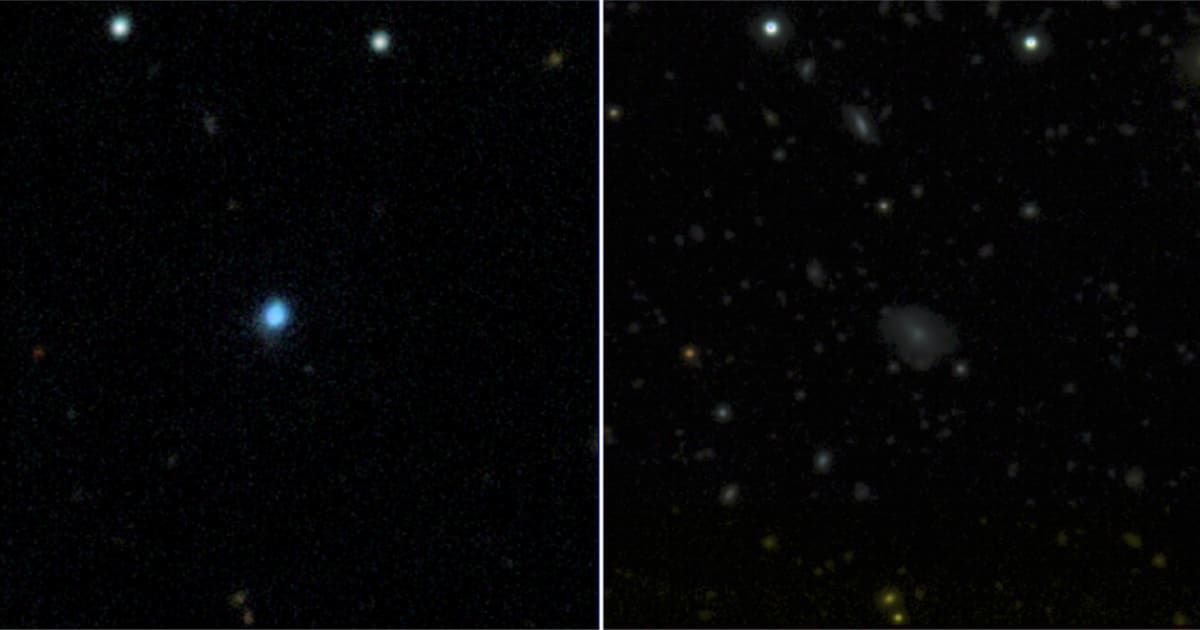

See the little dot? New studies of that blue flash from the distant universe (a "Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient") indicate it was caused by a black hole swallowing an entire star.

— Corey S. Powell (@coreyspowell) January 11, 2026

For a moment, it blazed as bright as 100 billion Suns. https://t.co/DDubsyjfOr pic.twitter.com/Sy2sLWjcYu

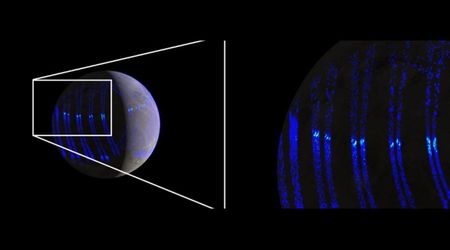

The object, now officially known as AT2024wpp and unofficially dubbed "the Whippet," is a member of the rare and not-so-well-understood class of space explosions termed Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients, or LFBOTs. They are bright enough to outshine about 100 billion Suns but vanish in a matter of days before most telescopes can react. The Whippet is especially significant among these since it is the brightest known LFBOT discovered yet.

The Whippet was first spotted in September 2024 by the Zwicky Transient Facility. Initial follow-up data from NASA’s Swift satellite and the Liverpool Telescope revealed that the blast was scorching hot and churning out intense X-rays, but scientists were scratching their heads about what they weren’t seeing. During an LFBOT explosion, the debris should slam into surrounding gas, creating distinctive chemical "fingerprints" in ultraviolet and optical light.

In the Whippet's case, those signatures could not be detected even with the Hubble Space Telescope. The space around the explosion looked empty, even though theory said that it should be crowded with stellar debris. Ultimately, the mystery was solved by the National Science Foundation's Very Large Array (VLA) and Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). These radio telescopes do not depend on light signatures; instead, they can follow shock waves.

The radio data revealed a shock wave that charged outward at 20% of the speed of light, which had then struck a dense pocket of gas located very close to the explosion. Immediately, the scientists realized that the gas had never disappeared—the explosion's own power had simply cloaked it. The X-rays produced by the blast were so intense that they stripped electrons off the nearby gas. This ionization effectively erased the chemical fingerprints that optical and ultraviolet telescopes usually detect.

The researchers recreated the Whippet's last moments by merging data from various light spectrums. They think a nearby star was consumed by a massive black hole, which is what caused the explosion. The star started to lose its outer layers as the black hole spiraled toward its victim, producing a dense gas bubble. After the core was torn apart, its debris arranged itself into a hot disk that acted as the black hole's food. This feeding frenzy produced a strong wind that collided with the gas that had previously been shed, lighting it up from radio to X-rays. Later observations from Keck, Magellan, and even the Very Large Telescope revealed faint traces of hydrogen and helium traveling at 6,000 km/s. This suggests that a dense structure survived the initial blast.

More on Starlust

Record-breaking, wobbling black hole jets are starving a nearby galaxy of stars

Astronomers surprised to witness a young star's jet backfire, triggering dramatic cosmic explosion