Scientists surveyed over 8,000 galaxies—the increasing number of active black holes baffled them

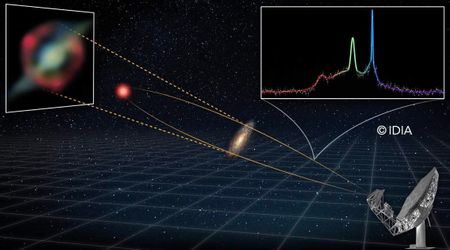

Astronomers have found a remarkably large number of active black holes in small and medium-sized galaxies, which implies that such cosmic engines are actually much more common than previously assumed. The study, presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting, provides the most detailed "population count" to date of Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN), the bright centers of galaxies powered by hungry black holes.

Researchers from Harvard & Smithsonian and the University of North Carolina analyzed more than 8,000 nearby galaxies and shifted known statistics significantly. While previous assessments had found only about 10 active black holes for every 1,000 dwarf galaxies, the new census reveals the actual number lies between 20 and 50. Of course, the numbers are bigger for medium- and large-sized galaxies, with 16 to 27% of the former and 20 to 48% of the latter having shown signs of active black holes.

"The intense jump in AGN activity between dwarf galaxies and mid-sized, or transitional galaxies tells us something important is changing between the two," said Mugdha Polimera, an astronomer at the CfA and the lead author of the new census, per the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics news release. "It could be a shift in the galaxies themselves, or a sign that we’re still not catching everything in the smaller ones and need better detection methods. Either way, it’s a new clue we can’t ignore."

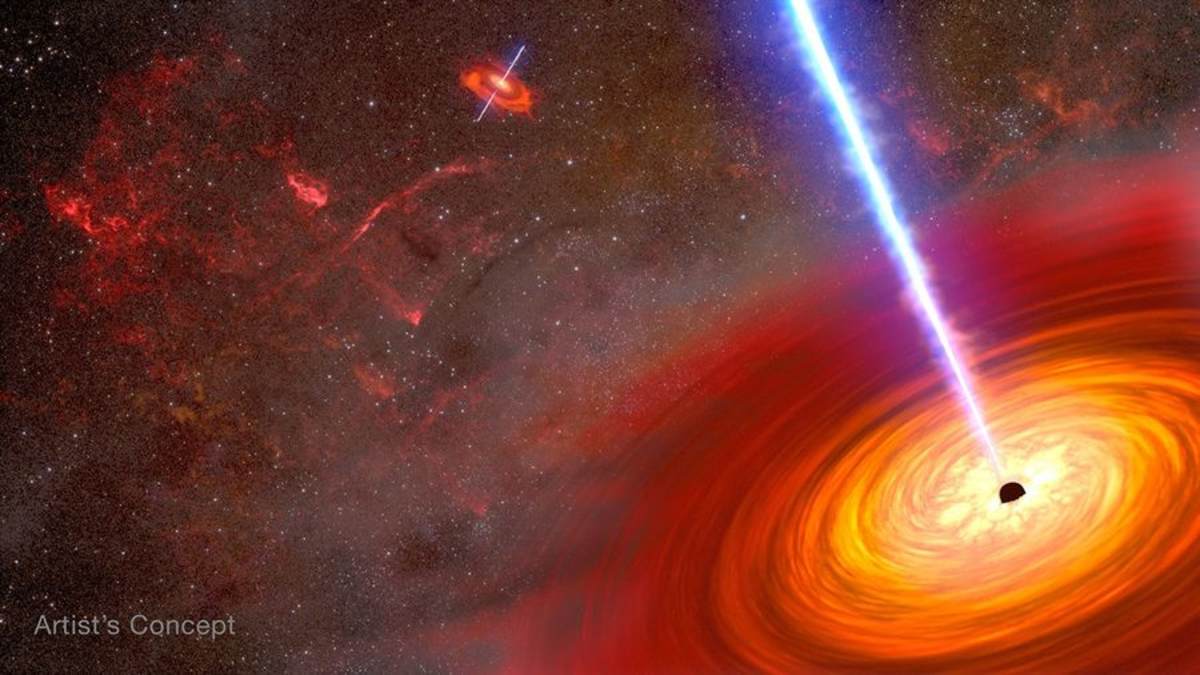

For decades, the glare of intense star formation has masked the faint signals of smaller black holes. The apparent solution lay in combining optical, infrared, and X-ray data to see through the dust and starlight. "Cutting through the glare of star formation reveals massive black holes that have slipped under the radar in dwarfs, but we're still trying to figure out why black holes are suddenly more common in galaxies like our own," said Sheila J. Kannappan, a professor at UNC and co-author of the study. She went on to say that since the Milky Way probably formed from the merger of several smaller galaxies, understanding these "dwarf" black holes is crucial to tracing our own galaxy's history.

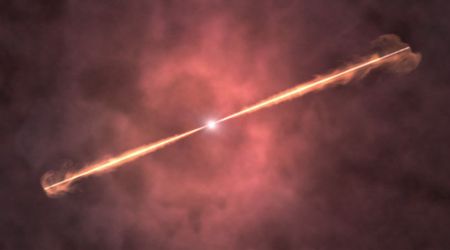

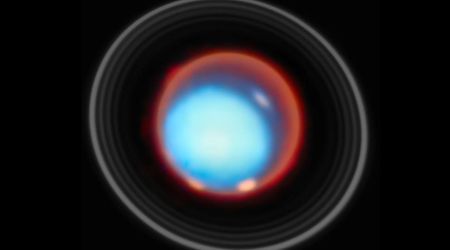

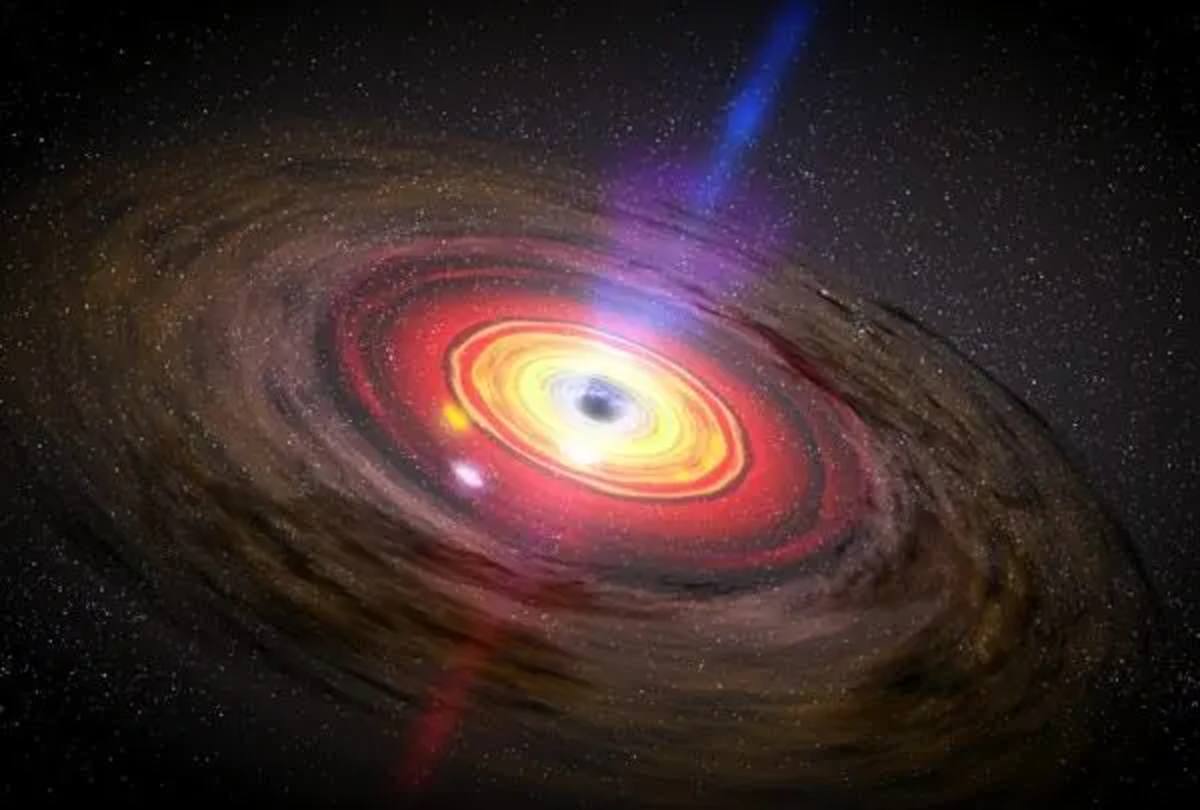

At the center of galaxies, these AGN act as enormous gravity wells that emit strong winds and energy jets, per NASA. Scientists are able to follow them by observing accretion disks, enormous rings of gas and dust revolving around black holes. These particles rub against one another as they orbit just outside the black hole's edge, producing a great deal of heat and light. The incredibly intense jets and winds released by black holes along strong magnetic fields are, in fact, some of this material.

Despite the breakthrough, Polimera and the team warn that the new percentages are estimates and may change as observations become more complete. The team is working to release the measurements that the study employed to allow other researchers to build on the findings.

More on Starlust

Hubble Space Telescope unveils striking portrait of a spiral galaxy harboring an active nucleus

Hubble captures active black hole devouring spiral galaxy 250 million light-years away