Astronomers discover supermassive black holes hiding behind cosmic dust for billions of years—until now

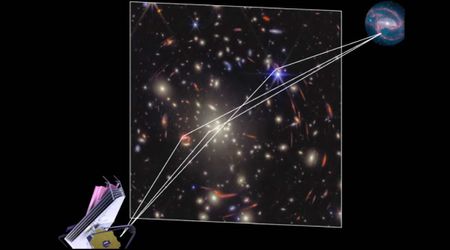

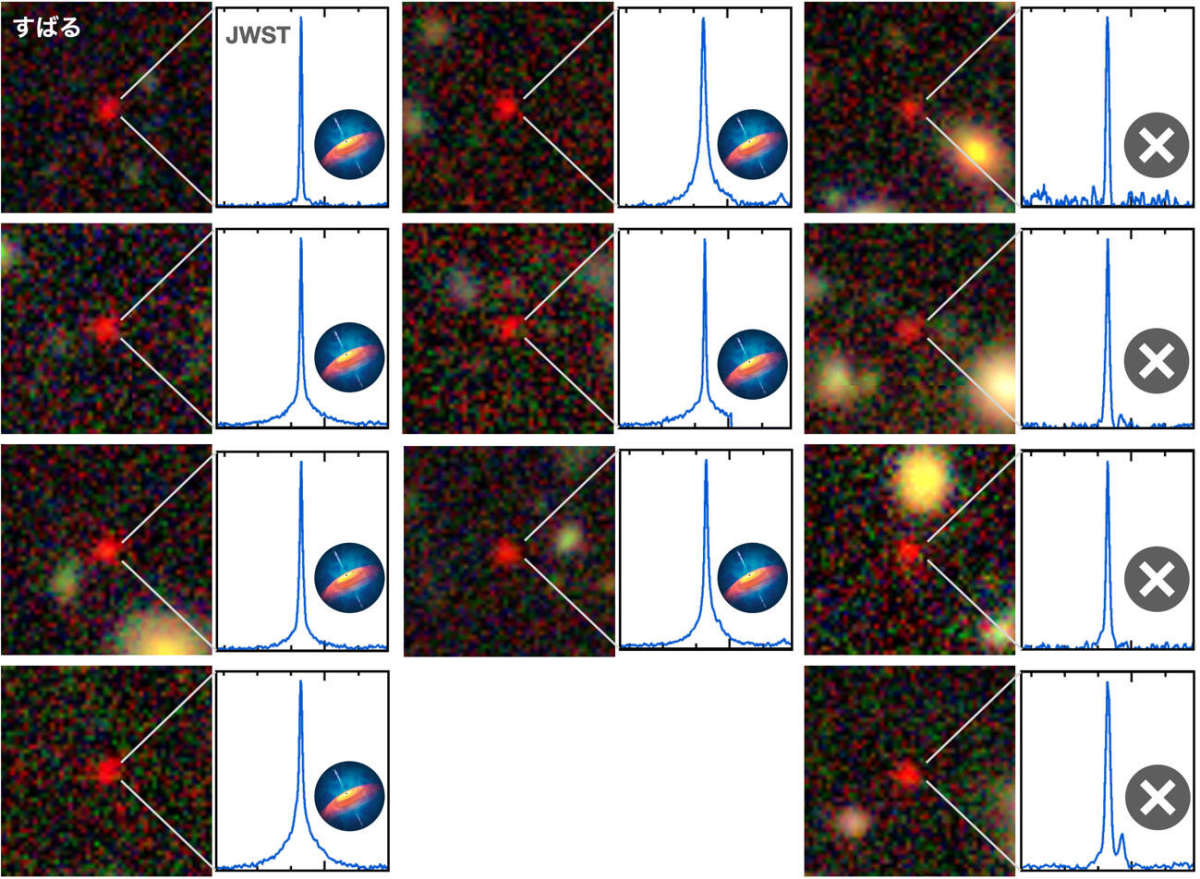

An international research team found supermassive black holes shrouded with dust in the early Universe. The team started by identifying candidate galaxies that could host supermassive black holes using the Subaru Telescope. These black holes shine like quasars as they consume the matter that surrounds them, as published in The Astrophysical Journal. This was confirmed by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and the team of scientists from Ehime University and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) reevaluated the discoveries.

This is the first discovery of such a hidden but bright quasar in the early Universe. This indicates that bright quasars used to be at least twice as common in the early universe, unlike what was thought before. Almost all galaxies in today’s universe, around 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, host supermassive black holes. According to the Subaru Telescope, these black holes are dormant but emit strong radiation when consuming surrounding matter. This intense radiation is believed to affect the growth and evolution of its host galaxy by expelling the gas inside it.

Astronomers using the #SubaruTelescope and #JWST have discovered "dust-shrouded supermassive black holes" less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang — suggesting bright quasars were at least twice as common as previously thought!https://t.co/BlQpRdA8eM pic.twitter.com/2O8bumuyeL

— Subaru Telescope Eng (@SubaruTel_Eng) September 9, 2025

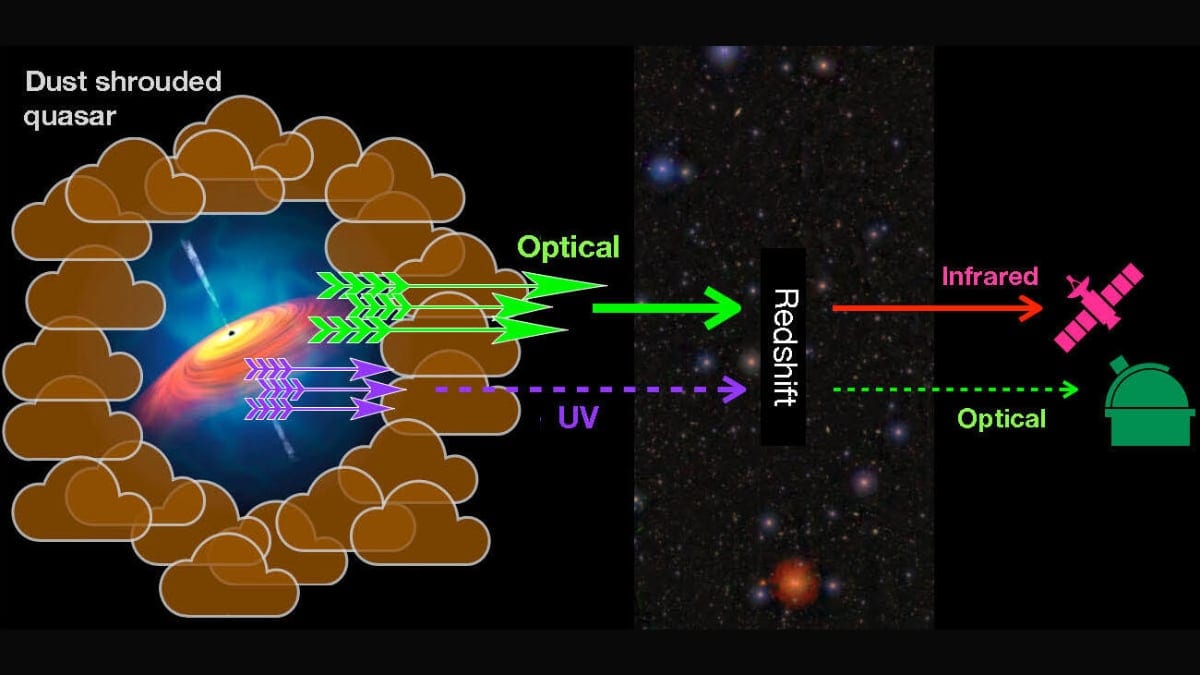

These black holes were present in the universe a billion years after the Big Bang, so they likely formed much earlier. Experts peeked into the Cosmic Dawn to understand how they formed, and there are two criteria based on the number of black holes detected. If they are larger in number, they form frequently as remnants of the first-generation stars. If low, then they formed under special conditions, like the direct collapse of massive objects due to self-gravity. A quasar is identified using ultraviolet light, which disperses when the black hole is within a galaxy.

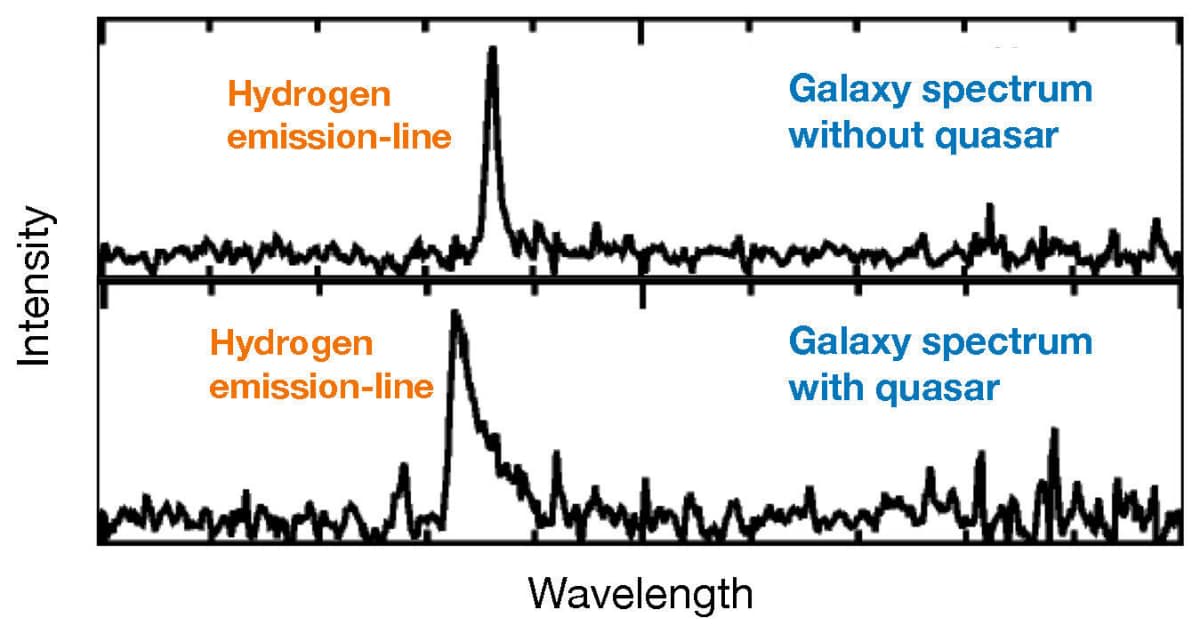

The team focused on the most luminous galaxies in the wide-area survey done using the Hyper Suprime-Cam on the Subaru Telescope (HSC-SSP). Signs of a powerful energy led them to suspect the presence of quasars, but the JWST was the game changer. This allowed us to detect visible light from these galaxies to see through the dust that blocks ultraviolet light. NIRSpec spectrograph of the JWST targeted 11 of the most luminous galaxies, seven of which had clear and broad emission lines, an evident sign of a quasar, confirming the presence of dust-shrouded quasars.

The team concluded that dust-obscured quasars are at least as common as conventional quasars. This meant that the number of bright quasars in the early Universe is at least twice as high as previously thought. They plan on researching quasars further to identify if they fundamentally differ from conventional quasars. They also plan to use the ALMA telescope to study the host galaxies in detail, highlighting the influential components. The conditions in and around the black holes could help understand how they are sustained and maybe provide hints of their origin.

They also hoped to expand the search for such black holes, which could provide a bigger chance of discovering the same again. Understanding such unique components of the universe helped us to gain more knowledge about the early origins of life in the galaxy and its evolution. These events have had major influences on the universe that we see today, and learning about them is like learning about our own past. Astronomers and space scientists hope to gain more knowledge about the vast space beyond us for the very same reasons.

More on Starlust

Webb Telescope illuminates hidden black holes feasting on stars in dusty cosmic corners