Ancient Pablo's galaxy starved to death as its own black hole cut off supplies

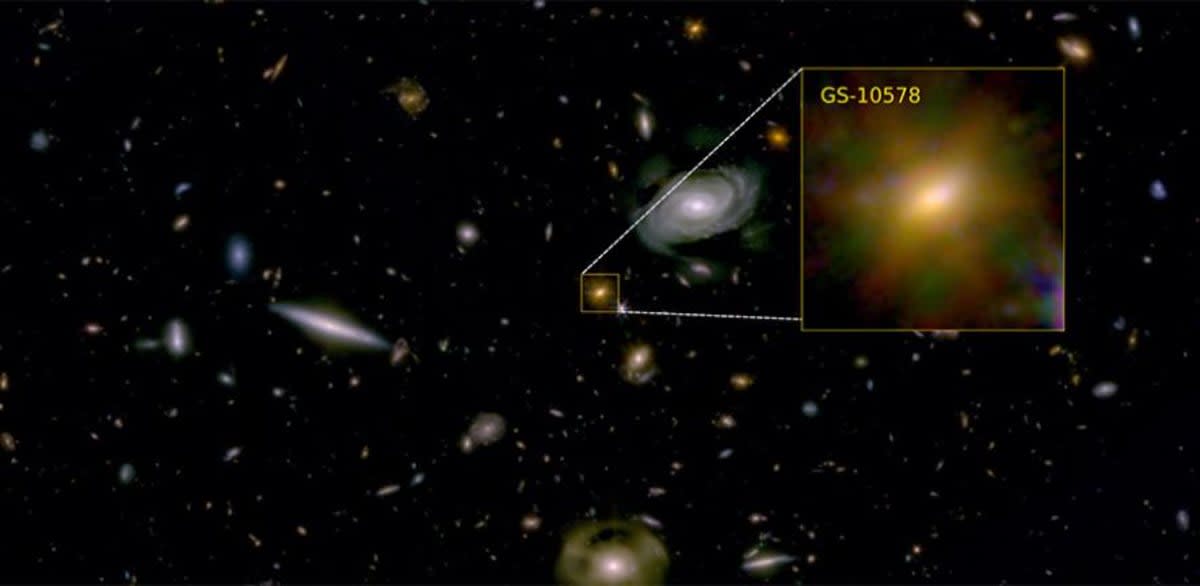

Astronomers have found the biggest "dead" galaxy from the universe's early days that stopped growing not because of a single cataclysmic event, but because its central black hole slowly cut off its life support. Officially called GS-10578, but affectionately nicknamed "Pablo's Galaxy" after the astronomer who first observed it in detail, this galaxy existed just about three billion years after the Big Bang.

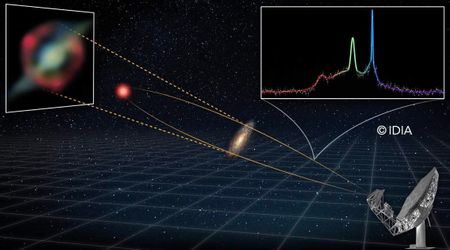

But despite its age, it is incredibly heavy, roughly 200 billion times the mass of our Sun. Yet data from the James Webb Space Telescope and the ALMA radio telescope reveal it has completely stopped producing new stars. The galaxy's central supermassive black hole acted like a cosmic gatekeeper, repeatedly heating up or pushing away the cold gas needed to create stars. "Even with one of ALMA’s deepest observations of this kind of galaxy, there was essentially no cold gas left. It points to a slow starvation rather than a single dramatic death blow," explained Dr. Jan Scholtz of the University of Cambridge and first co-author of the study published in Nature, in a statement.

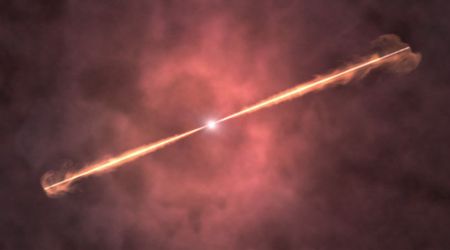

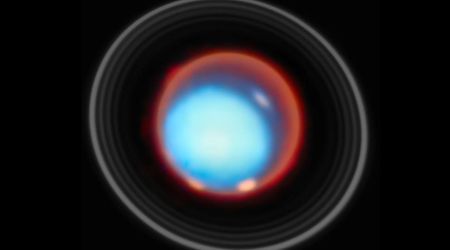

The research team searched for carbon monoxide, a signal for the cold gas that fuels star birth. After almost seven hours of searching with ALMA, they found nothing. This absence proved the galaxy had used up all its fuel. Meanwhile, JWST detected gas winds screaming out from the black hole at 400 kilometers per second. These winds were dumping the equivalent of 60 Suns' worth of gas every year, which emptied the galaxy's reserves far quicker than expected—in as little as 16 to 220 million years.

In fact, by reconstructing the galaxy's history, the researchers found that it had a "net-zero" gas problem, which means it didn't have new gas refill its tank. Despite internal turmoil, the galaxy remained an unexpectedly calm and neat rotating disk, proving it wasn't killed by a messy crash or merger with another galaxy. An efficient means of starvation led to a quick shutdown, with star formation ending roughly 400 million years before these observations.

The study helps explain why the James Webb telescope is finding so many old-looking galaxies in a young universe. "Before Webb, these were unheard of,” Scholtz said. “Now we know they’re more common than we thought – and this starvation effect may be why they live fast and die young." This finding represents a substantial change in our understanding of the life cycles of early galaxies. In order to determine whether this "slow starvation" is the main cause of the early demise of so many of the universe's earliest giants, the team has already secured an additional 6.5 hours of time with the MIRI instrument of the James Webb Space Telescope. The forthcoming observations will target the warmer regions of the galaxy to uncover more about exactly how the supermassive black hole starved it.

More on Starlust

NASA's IXPE spends over 600 hours observing a galaxy cluster, solves a major black hole mystery

Astronomers witnessed black hole shredding a massive star like it was 'preparing a snack for lunch'