Supermassive black holes may be surprisingly picky eaters, new study finds

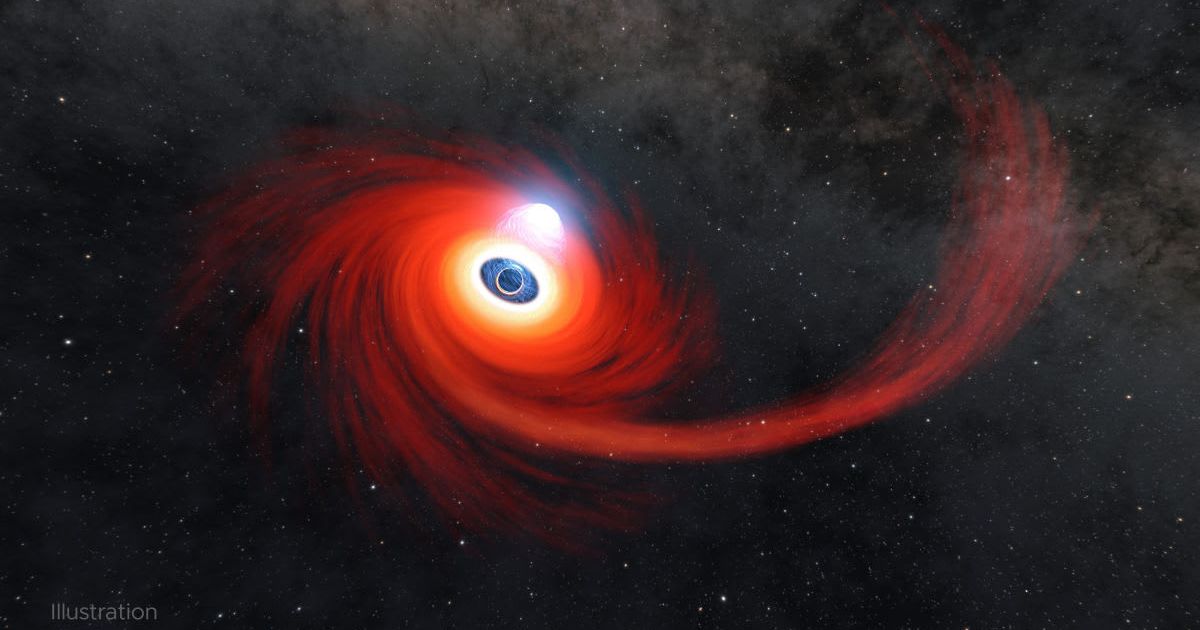

A recent study has discovered that supermassive black holes may not exactly be the greedy monsters who eat everything they can get their metaphorical hands on. Instead, they can be quite picky eaters, and this habit has a significant impact on their growth, per the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

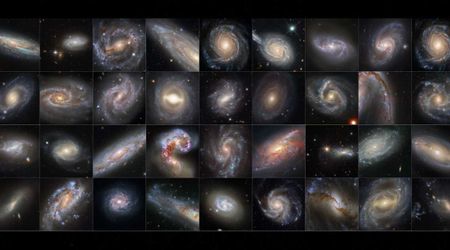

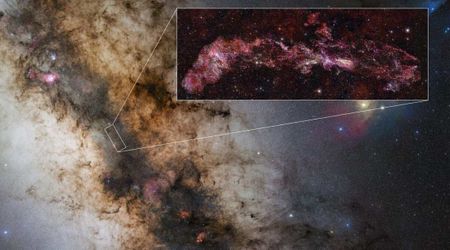

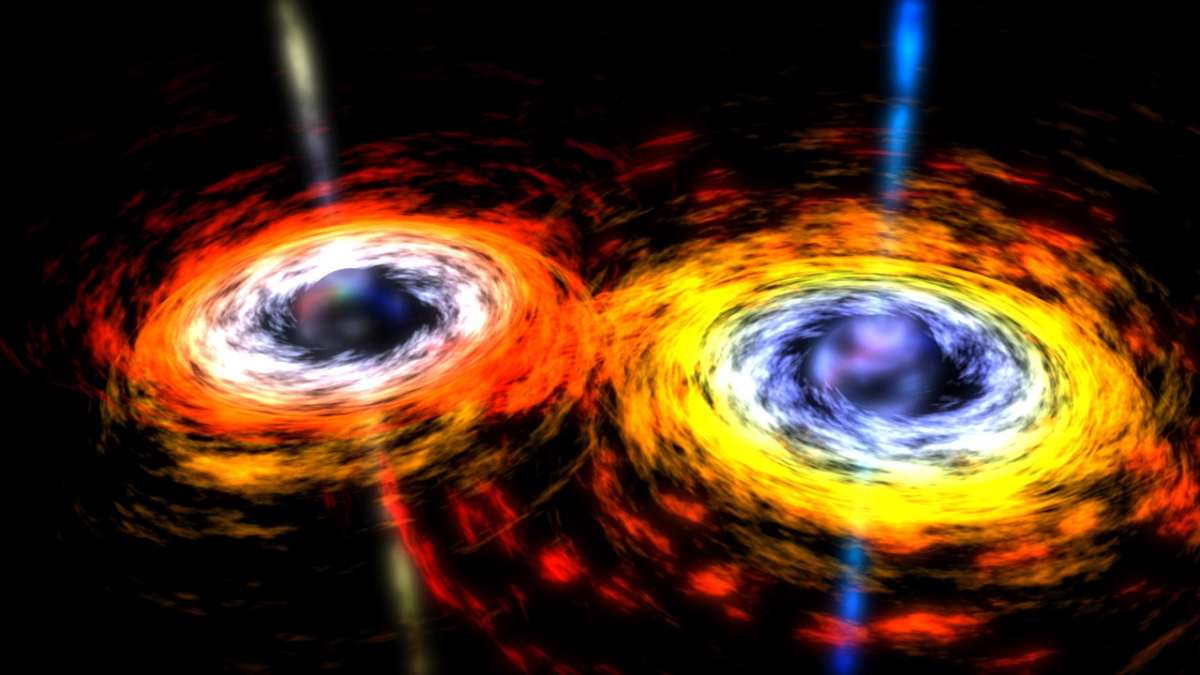

An international research team led by Makoto A. Johnstone of the University of Virginia used the ALMA telescope in Chile to investigate seven nearby merging galaxy pairs hosting supermassive black holes. Such catastrophic events usually direct huge quantities of cold gas to the center of each galaxy, which is also where the supermassive black holes are located. Events like these can excite one or both black holes, turning them into AGNs (Active Galactic Nuclei)—one of the most energetic objects in the universe.

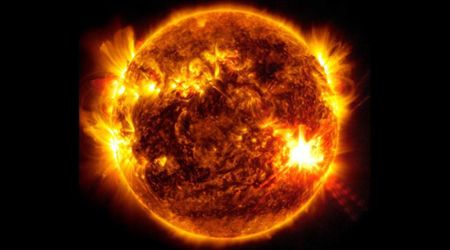

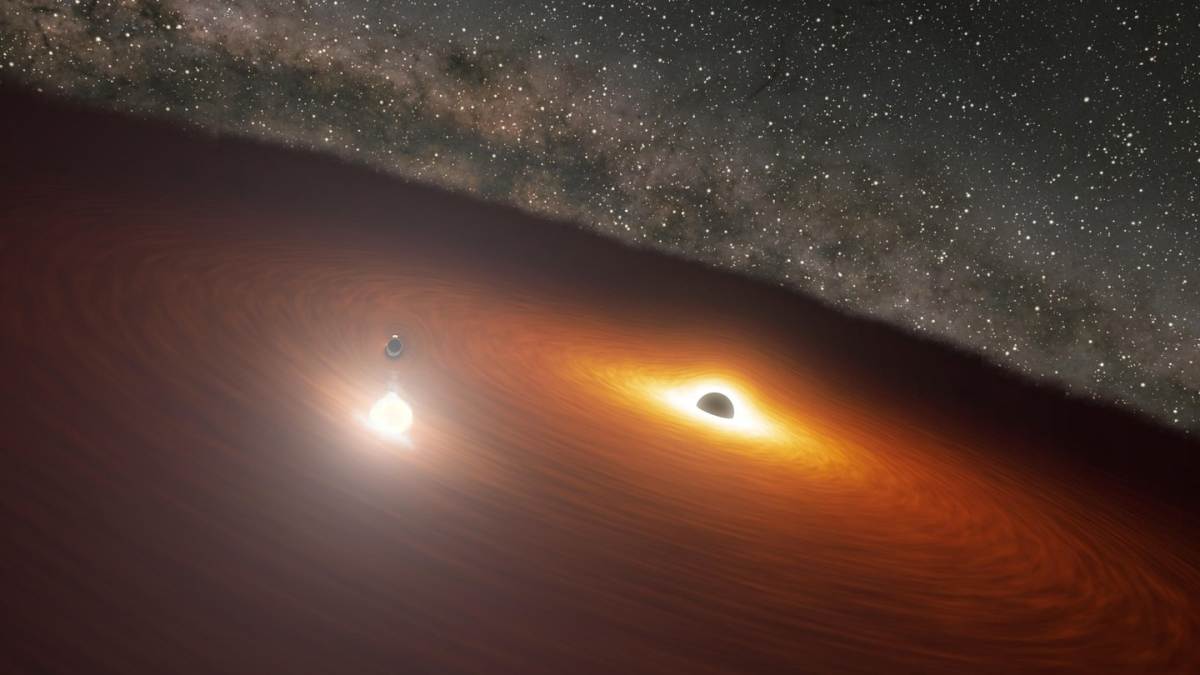

However, the observations revealed that many black holes, even if they are in the middle of a gas cloud, are choosing to "nibble" instead of "gorge," showing an extremely low appetite. This is evident from how their brightness, an indicator of how fast they are eating, is not increasing relative to the amount of "food" they have access to. Moreover, the scientists reported a "lone eater" phenomenon; oftentimes in a pair of merging black holes, one would be active while the other, despite sharing the same rich gas supply, would be quiet.

"The inefficiency of the observed supermassive black hole growth, even when dense reservoirs of molecular gas are present, raises questions about the physical conditions necessary to trigger these growth episodes," Johnstone explained. "In addition to occurring in extreme dusty environments, the AGN activity is likely highly variable and episodic, explaining why it has been so difficult to detect two simultaneously active black holes in mergers."

The team also compared mergers having two actively feeding black holes with mergers where only one black hole showed signs of appetite. While some of the inactive black holes did not have access to cold gas, others simply refused to eat, perhaps because it wasn't their feeding time yet. "These unique ALMA observations show how black holes are actively being fed during a major galaxy merger, an event that we strongly suspect is critical in setting up the observed connection between black hole growth and galaxy evolution. It is only now, thanks to the unique and revolutionary ALMA capabilities, that this study is feasible," said Ezequiel Treister, co-author of the study.

The research has also documented that several active black holes are located slightly off-center in their galaxies. The scientists think that this offset is the result of the mergers' intense gravitational chaos. In short, the study suggests that galactic mergers supplying supermassive black holes with enough energy for them to start feeding is only half the job done. Whether these black holes will actually start eating and hence light up depends on a number of other factors, such as timing, turbulence, and the availability of dust.

More on Starlust

Astronomers confirm first triple system with actively feeding supermassive black holes