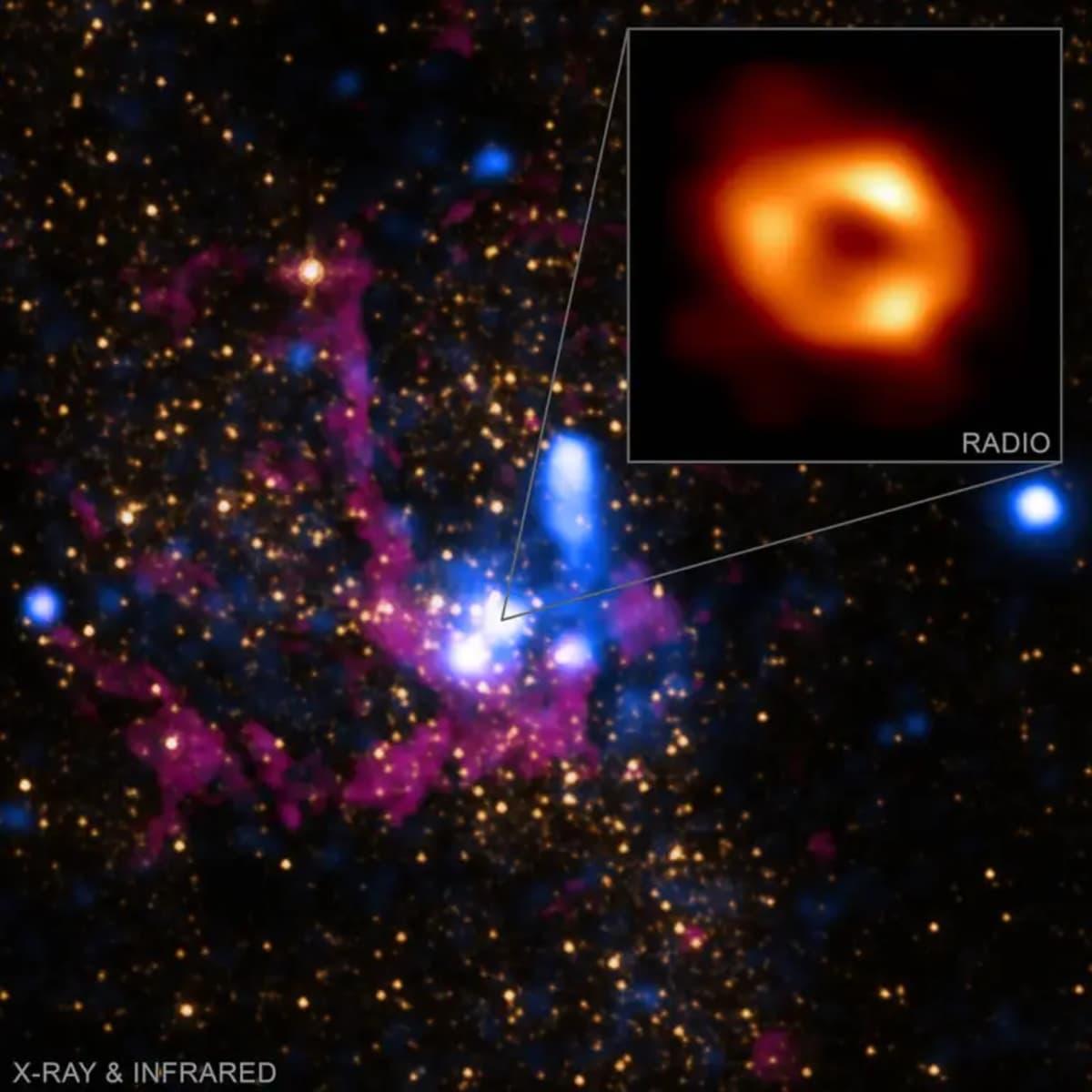

Not every galaxy has a supermassive black hole like the Milky Way's, NASA's Chandra Telescope finds

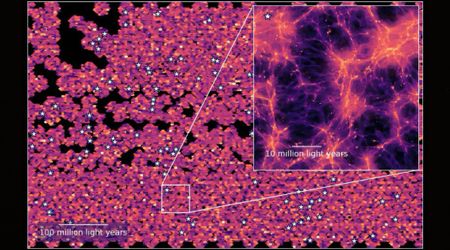

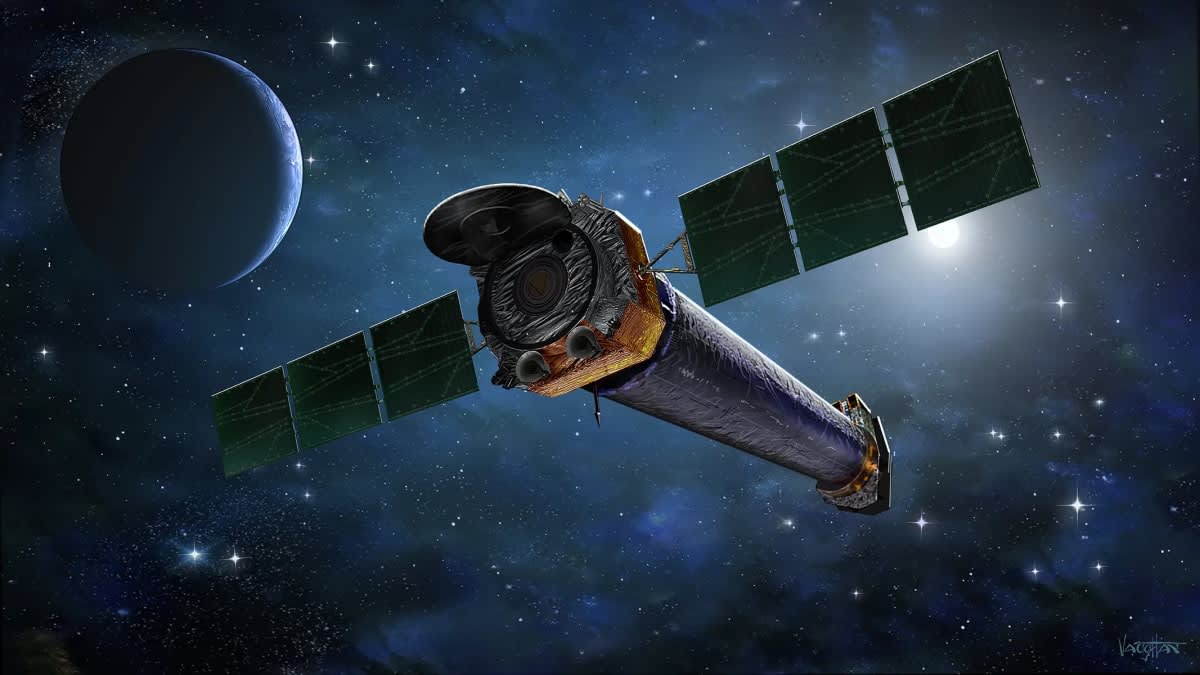

Astronomers have long believed that pretty much every galaxy, no matter how big or small, has a supermassive black hole lurking right at its center. It's been one of those "everyone knows this" ideas in astronomy for years. But new work with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory is making astronomers rethink that. A team of researchers looked at more than 1,600 galaxies that Chandra has watched over the past twenty-plus years. They studied everything from giant galaxies ten times bigger than our Milky Way to tiny dwarf galaxies that have only a fraction of the stars we do.

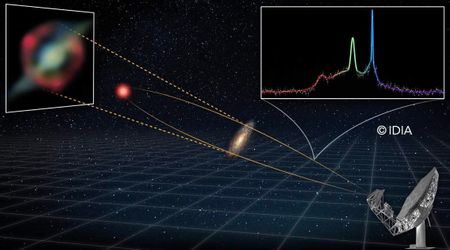

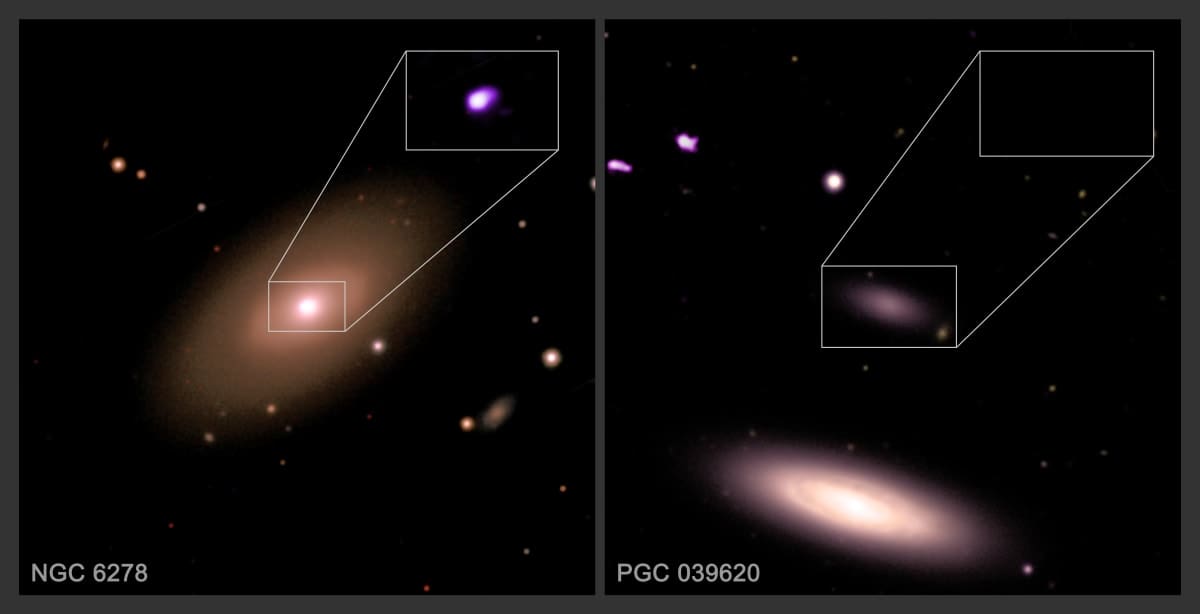

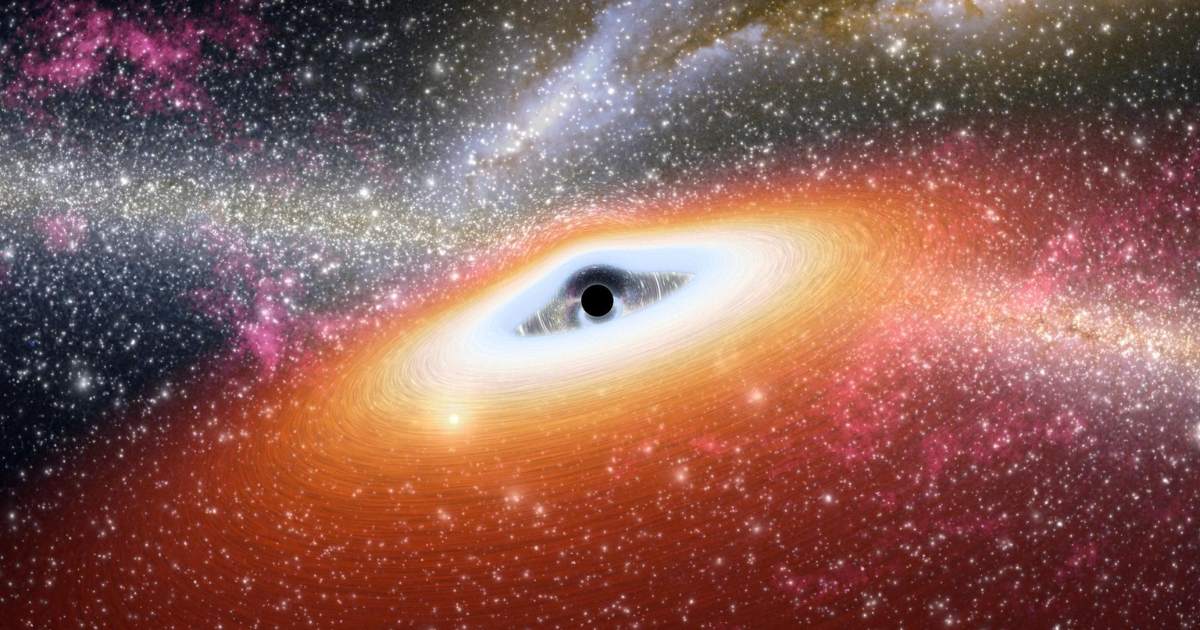

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal, highlight stark differences in how often black hole signatures appear across galaxies of different sizes. One of the most striking results is that only about 30 percent of dwarf galaxies appear to host supermassive black holes. “It’s important to get an accurate black hole head count in these smaller galaxies. It’s more than just bookkeeping," said lead author Fan Zou of the University of Michigan, per NASA. Our study gives clues about how supermassive black holes are born. It also provides crucial hints about how often black hole signatures in dwarf galaxies can be found with new or future telescopes.” The team relied on Chandra’s X-ray capabilities to identify black holes actively pulling in material. When gas spirals into a black hole, friction heats it and produces X-rays, creating a detectable beacon.

In the big galaxies, things looked exactly as expected. Over ninety percent of them had a bright X-ray glow coming from the middle, the classic sign of a supermassive black hole happily munching on gas and dust. Even galaxies around the size of the Milky Way almost always showed that telltale sign. But when the researchers turned to the smaller galaxies, the picture changed completely. In dwarf galaxies with less than about three billion times the Sun's mass (think something like the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of our galactic neighbors), that bright X-ray signal was almost nowhere to be found. Hardly any of them had it. This could mean two things: either the smaller galaxies contain a smaller number of these massive black holes, or the X-rays they generate are not strong enough for Chandra to detect.

Co-author Elena Gallo, also from the University of Michigan, summarizes their findings: “We think, based on our analysis of the Chandra data, that there really are fewer black holes in these smaller galaxies than in their larger counterparts.” To reach this conclusion, the team modeled how much gas should fall onto black holes of different masses. Smaller black holes tend to attract less material, making them naturally dimmer. Chandra would miss many of these faint objects, and the researchers confirmed that this effect accounts for part of the drop in detections among low-mass galaxies. Even after accounting for this, however, there remained a substantial deficit, too large to explain through faintness alone. The simplest explanation is that many dwarf galaxies do not possess a central black hole at all.

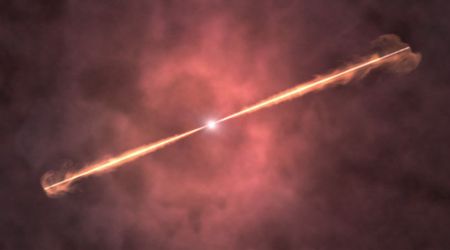

This outcome has direct consequences for theories about how supermassive black holes first form. Two leading ideas have been debated for years. In one scenario, massive clouds of gas collapse directly into black holes thousands of times the Sun’s mass from the very beginning. In the other, supermassive black holes grow out of much smaller black holes left behind by collapsing stars.

Co-author Anil Seth of the University of Utah points out the implication: “The formation of big black holes is expected to be rarer, in the sense that it occurs preferentially in the most massive galaxies being formed, so that would explain why we don’t find black holes in all the smaller galaxies.” The results of the study align with the model where supermassive black holes form through direct collapse, bypassing the smaller “seed” stage. If stellar remnants were the primary seeds, dwarf galaxies would be expected to host black holes at roughly the same rate as large galaxies, which data collected from the Chandra clearly contradicts.

Beyond shaping theories of black hole origins, this discovery also affects expectations for observations in the near future. Fewer black holes in smaller galaxies would mean fewer mergers detected as gravitational waves by missions like the upcoming Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. It also points to a smaller number of black holes tearing apart stars in dwarf galaxies.