Artemis II's free return trajectory: What it is and how it will protect the astronauts

Four astronauts — NASA's Christina Koch, Victor Glover and Reid Wiseman, along with Canadian Space Agency's Jeremy Hansen — will fly aboard the Orion spacecraft on NASA’s 10-day Artemis II mission that is destined to circle around the Moon next month. The take-off is slated to happen no earlier than February 6. However, exploring space beyond Earth is fraught with dangers. An inadvertent human error or a technical glitch can divert a spacecraft from its trajectory or harm its crews. For instance, an oxygen-tank explosion on Apollo 13’s service module forced it to abandon a lunar landing. Space shuttle Columbia broke up during re-entry, killing all 7 crews. Such disasters prompted NASA engineers to think of how Artemis II crews can be safely returned to Earth. They have decided to resort to a gravity-assisted free-return trajectory.

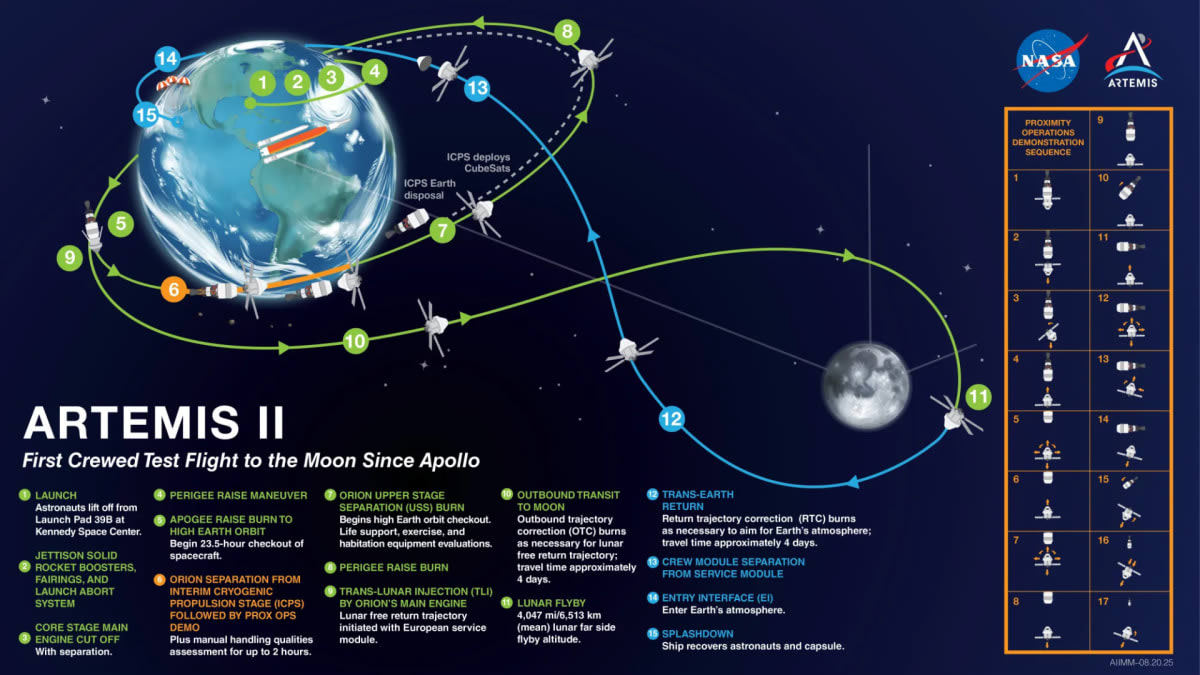

“After launch and initial Earth-orbit operations, Orion will perform a trans-lunar injection burn to send it toward the Moon, then pass behind the Moon, using lunar gravity to bend its path and redirect it back toward Earth without needing large engine burns on the return leg,” said Anand Kumar Sharma, a former distinguished scientist at the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) who was also a part of the Chandrayaan-2 mission team, in an email interview with Starlust. This, he said, will culminate in a high-speed re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere and a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

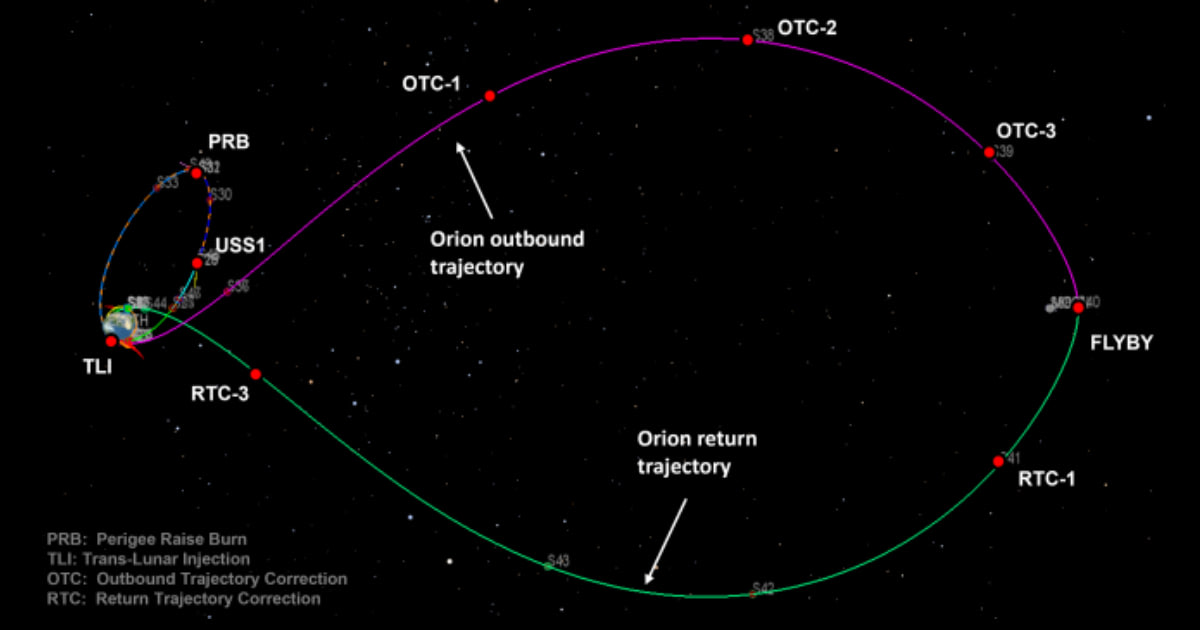

Trans-lunar injection (TLI) is an orbital maneuver performed in low-Earth orbit that makes sure that the Orion spacecraft is put into a free-return trajectory. Three hours after TLI, the first outbound trajectory correction burn (OTC1) is slated to happen. OTC is a precise maneuver executed by a spacecraft (like Orion) during its transit to the Moon, typically after the TLI, to fine-tune its path and correct navigational errors.

The second OTC burn (OTC2), 24 hours after TLI and the third OTC burn (OTC3) have been planned to occur 24 hours prior to the lunar flyby while avoiding the crew's sleep period, according to a study by NASA. As Orion begins its journey home, the first return trajectory correction burn (RTC1) is performed one day after the lunar flyby. The last two return trajectory correction burns, RTC2 and RTC3, are executed both 21 hours and 5 hours prior to entry interface, respectively.

Guided by the NASA’s Deep Space Network, these three small return trajectory correction burns along the way will ensure the crews are ready for a safe return. “This ‘fail-safe’ rationale was key to Apollo 8’s flight in 1968, which used a free-return trajectory to send the first humans to orbit the Moon and back safely, and similar concepts later aided the safe return of Apollo 13,” Sharma pointed out. “India’s Chandrayaan-2 (2019) and Chandrayaan-3 (2023) missions employed a slower, fuel-efficient lunar transfer strategy in which multiple Earth-orbit-raising maneuvers gradually expanded the spacecraft’s orbit before trans-lunar injection, conserving propellant at the cost of longer travel time but reflecting the same underlying philosophy of exploiting orbital mechanics for efficiency and safety.”

However, re-entry will be one of the harshest tests: temperatures near 3,000°F, a plasma blackout, and parachute deployment before a Pacific Ocean splashdown, followed by U.S. Navy recovery. NASA engineers have learned lessons from the unmanned Artemis I test flight. To avert disaster, Orion will use a "skip entry," where the capsule dips into the upper atmosphere to generate lift and "skips" back out before entering again. This technique dissipates energy, reduces g-forces on the crews, manages heat loads, and allows for a more precise, targeted splashdown. The heat shield, made of an ablative, silica-fiber-filled material called AVCOAT, is designed to burn away at temperatures up to 5,000°F.

After slowing to 300 miles per hour, a multi-stage parachute system is deployed. This slows the capsule further to a safe splashdown speed of 20 miles per hour. Following splashdown, the U.S. Navy and specialized recovery teams will immediately secure the capsule and retrieve the crew in California. “Artemis II’s free-return journey offers redundancy in case of propulsion failure, conserves fuel and simplifies mission design, and draws on a proven approach from the Apollo era that helped protect astronauts during the first human voyages to the Moon,” noted Sharma, detailing how the free return trajectory would help with the safe return of the crew.

More on Starlust

NASA's Artemis II mission: Why the four astronauts won't land on the Moon

Artemis II astronauts enter quarantine as launch period inches closer