Astronomers finally spotted what they were searching for decades—1st coronal mass ejection from another star

Astronomers have hit a major milestone, confirming the first clear sighting of a powerful stellar explosion, a coronal mass ejection (CME), on a star that's not our Sun, according to the European Space Agency.

🆕 Astronomers have wanted to spot a 'coronal mass ejection', or CME, on a star other than our own for decades. And now they have! https://t.co/g7zcC8MREz

— European Space Agency (@esa) November 12, 2025

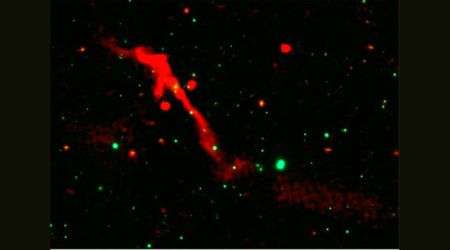

They used data from the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton space observatory and the LOFAR radio telescope to track a massive amount of material being blasted into space by a red dwarf star about 130 light-years away. While we know CMEs, which are huge bursts of stellar material that affect space weather, happen regularly on the Sun, actual proof of them happening on distant stars has been a challenge for astronomers for years. "Previous findings have inferred that they exist, or hinted at their presence, but haven’t actually confirmed that material has definitively escaped out into space," said Joe Callingham, the lead author from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON), whose study was published in Nature. "We’ve now managed to do this for the first time."

The breakthrough came from spotting a quick, intense burst of radio waves. This signal comes from the shock wave generated as the CME moved through the outer layers of the star and into interplanetary space. Importantly, this signal verifies that the material has made it out of the star's strong magnetic grip, which is a telltale sign of a CME event.

The star in question is a highly active red dwarf. It's smaller, cooler, and dimmer than our Sun, but it's rotating 20 times faster and has a magnetic field that's 300 times stronger. This type of star is the most common one hosting planets in the Milky Way. The analysis showed that the CME was zooming along at an incredible speed of 2400 kilometers per second, which is pretty rare for solar CMEs. Such a fast and dense ejection could strip away the atmospheres of any planets that are close by.

This discovery raises some serious concerns for the search for life. A planet might sit in its star's "habitable zone," where liquid water could theoretically exist, but if it gets hit regularly by these intense stellar storms, it could end up as a lifeless rock. "It seems that intense space weather may be even more extreme around smaller stars – the primary hosts of potentially habitable exoplanets," noted Henrik Eklund, an ESA research fellow. "This has important implications for how these planets keep hold of their atmospheres and possibly remain habitable over time."

In another recent study, scientists analyzing data from the European Space Agency's (ESA) Solar Orbiter have published the first clear analysis of magnetic field motion near the Sun's often-obscured south pole, a region absolutely critical to unlocking the mechanics of the Sun's fundamental 11-year activity cycle. The new data is essential not just for improving predictions of our own Sun's space weather.

More on Starlust

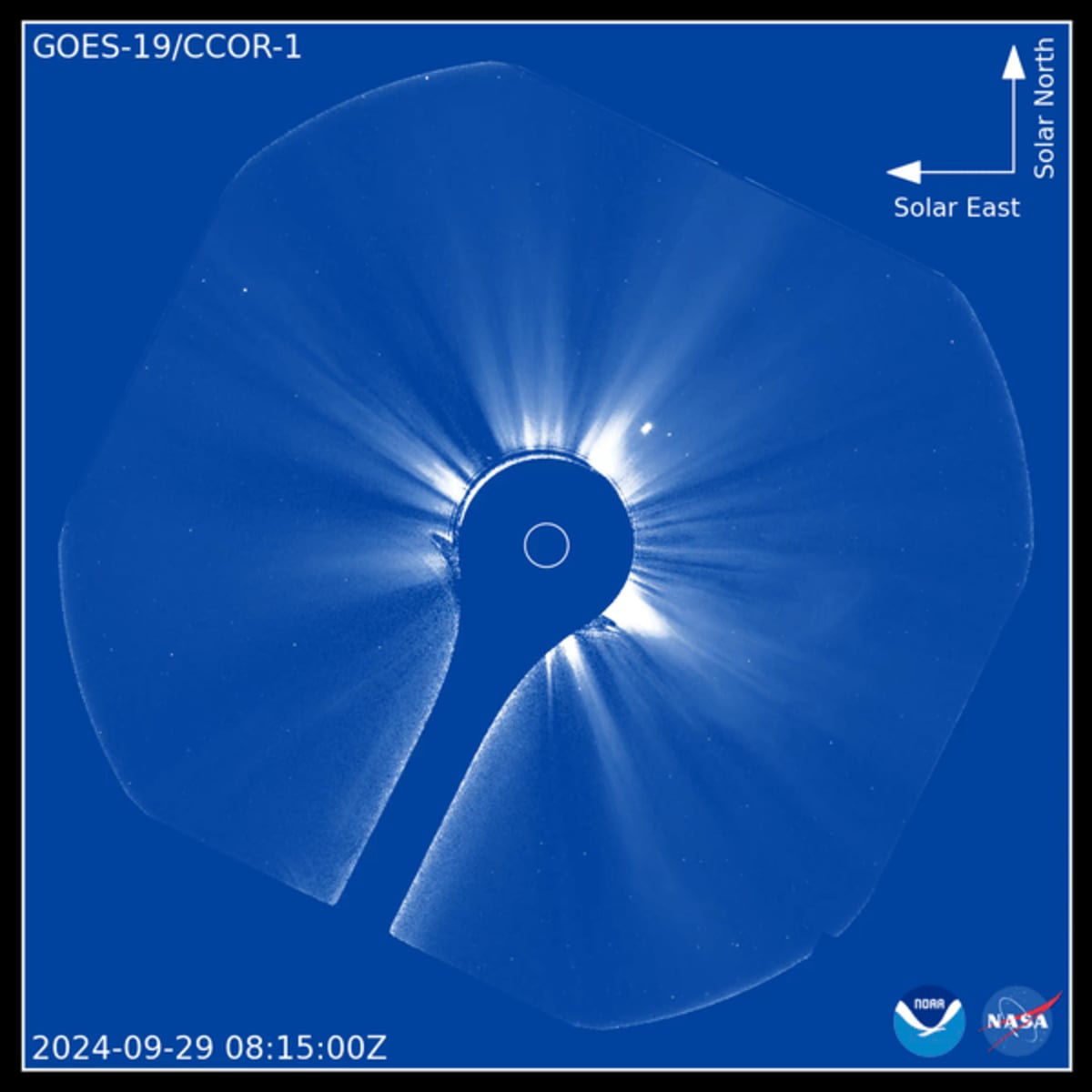

Triple coronal mass ejections are headed to Earth and could trigger auroras in northern skies

Solar Orbiter cracks one of the Sun's secret codes by tracing origins of superspeed electrons