The universe may be filled with Earth-like planets, new supernova model suggests

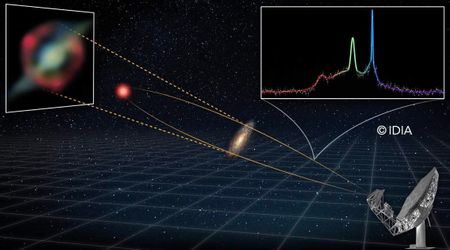

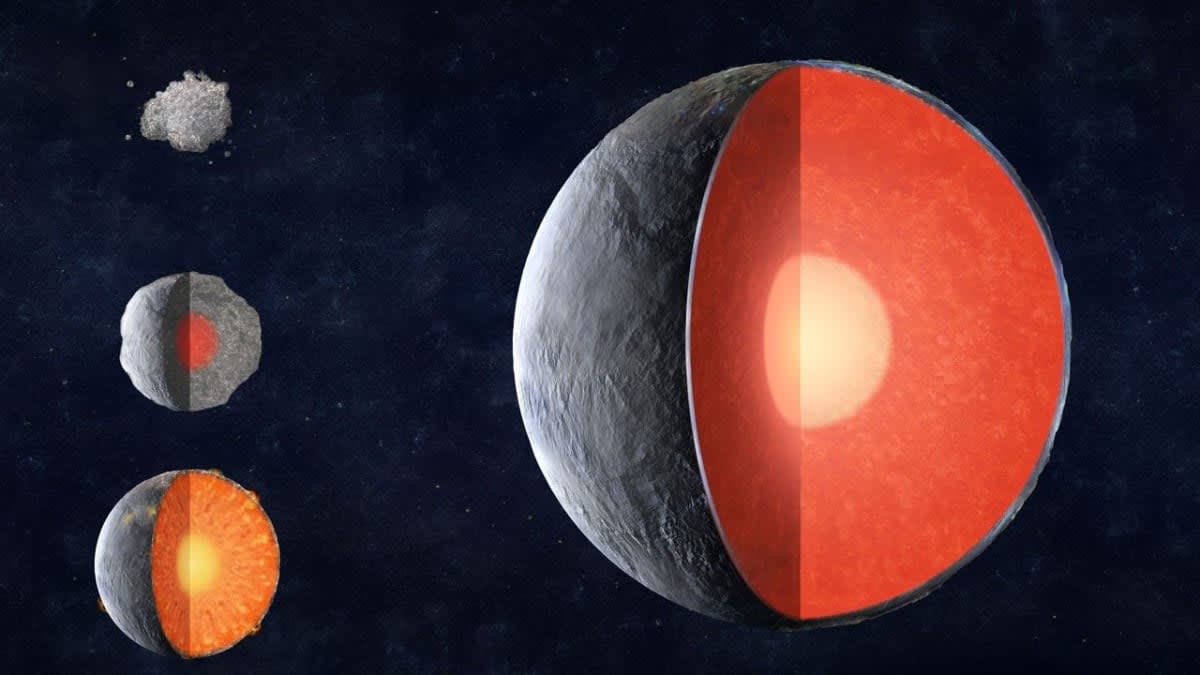

A new research paper, published in the Science Advances journal, has postulated that rocky planets like ours may be far more common than we previously believed. Previously, scientists had concurred that Earth-like planets grew from small rock-and-ice bodies that shed their water early on. This drying process required intense heat, driven mainly by the decay of short-lived radionuclides (SLRs) such as aluminum-26.

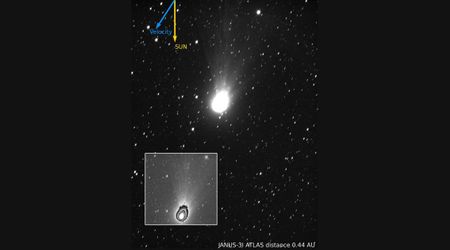

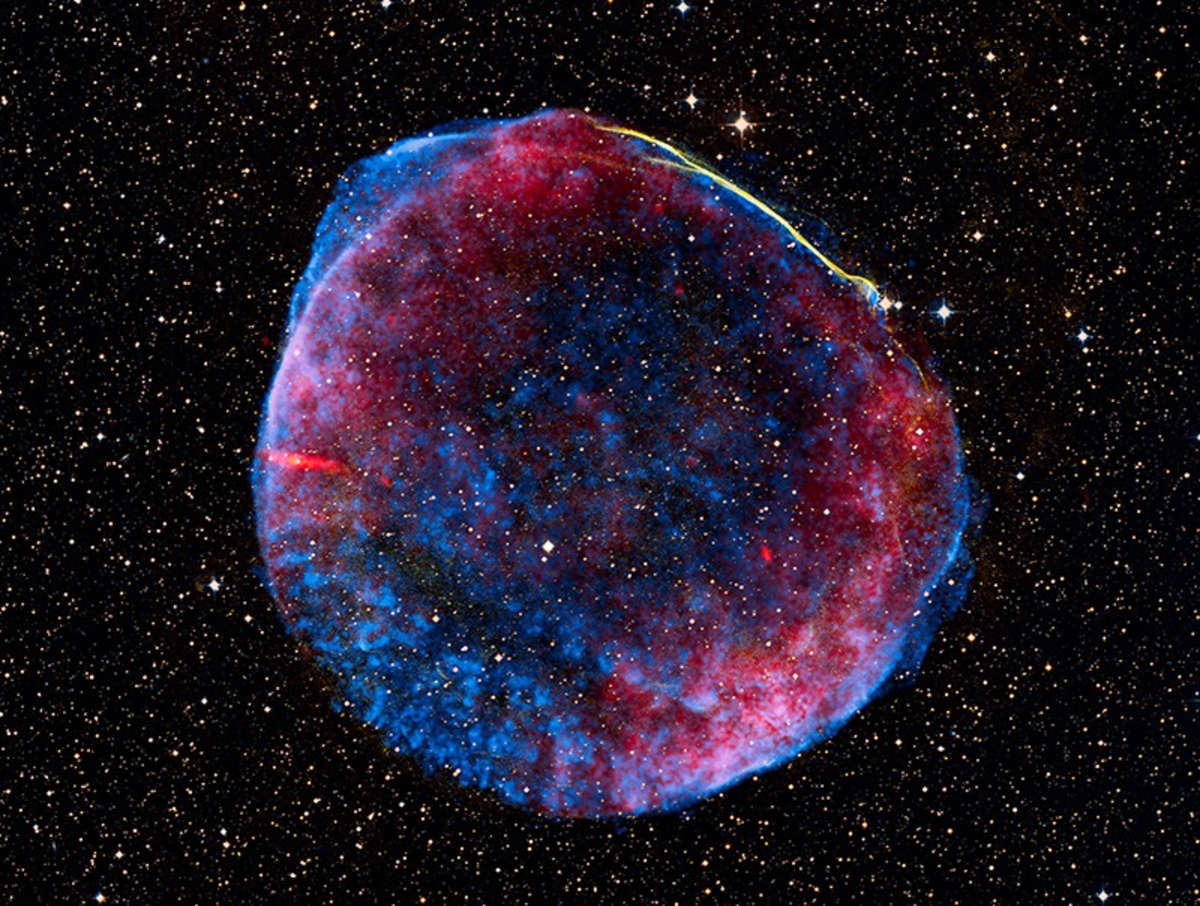

Ancient meteorites, which act as time capsules from that era, show that these radioactive materials were plentiful. What this new research, by Ryo Sawada of the University of Tokyo and his colleagues, postulates is that a nearby supernova (explosion of a star at its death) showered our young solar system with cosmic rays that were packed with radioactive ingredients that, in turn, set the stage for the formation of worlds that were rocky and dry (just like Earth).

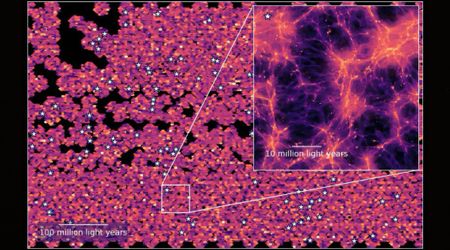

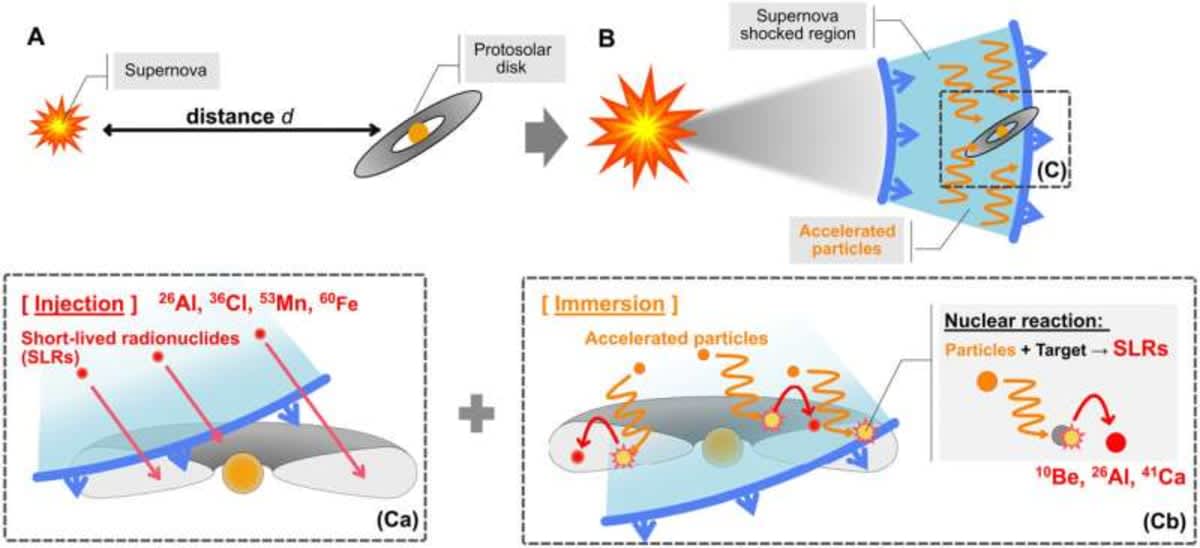

The researchers argue that this process was not only restricted to Earth but was far more widespread, giving rise to the suspicion that there could be many more planets like ours, lurking in the vast expanse of the universe. A big hurdle in this is that models that attribute all short-lived radionuclides to supernovae cannot account for the abundance observed in meteoritic samples. Achieving those levels would require an explosion at a distance close enough to disrupt or destroy the protoplanetary disk of the early solar system.

Now, the team led by Ryo thinks they’ve got a better fix for this model. They did it by creating their own model called the “supernova immersion” model, and it’s pretty smart. In the model that they set up, the supernova doesn’t have to be right next door. It can explode a safe distance away, about 3.2 light-years. From there, it does two things. First, it flings some radioactive dust, like iron-60, straight into the disk. But the real game-changer is the flood of high-energy cosmic rays it sends out. Those cosmic rays crash into normal stuff already in the disk and kick off reactions that make aluminum-26 right there on the spot.

When the researchers ran the numbers, it matched perfectly with what we see in ancient meteorites. That’s exciting because if this is how it happened for us, it probably happened for a lot of other stars, too. "Our results suggest that Earth-like, water-poor rocky planets may be more prevalent in the galaxy than previously thought, given that 26Al abundance plays a key role in regulating planetary water budgets," the researchers wrote. The team estimates 10 to 50 percent of Sun-like stars might have harbored SLR-abundant planet-forming disks akin to those in our solar system.

It doesn’t mean we’re about to find alien neighbors tomorrow. Life still needs a bunch of other things to go right. But it does mean the kind of planet life needs might be way more common than we thought. The universe is full of these massive blasts, sprinkling the ingredients everywhere. Turns out our little blue dot might just be one of many that got the perfect recipe.

More on Starlust

Nearby supernova explosions could be behind two of Earth's mass extinctions, says new study