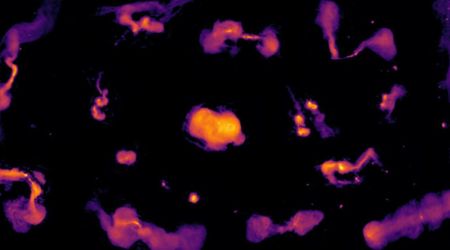

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope observes mysterious ultraviolet radiation in stellar nursery

Astronomers have observed ultraviolet (UV) radiation in a star nursery using the MIRI instrument onboard the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). To say this discovery is significant would be an understatement, as UV radiation around these protostars and their influence on the surrounding material pose a challenge to existing models that describe star formation.

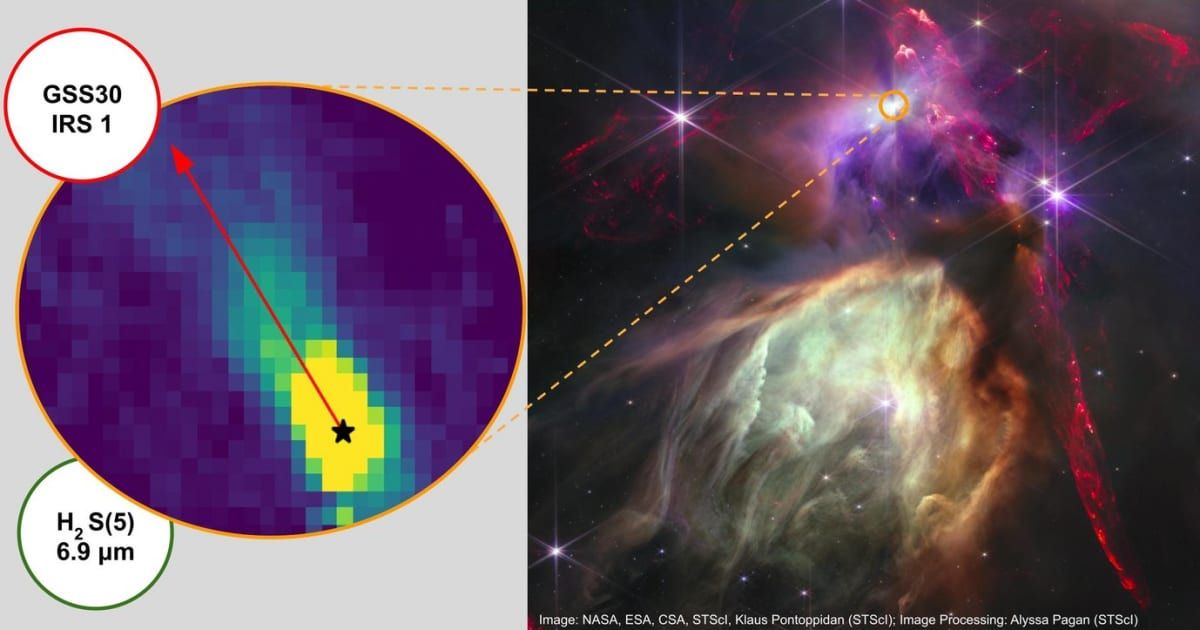

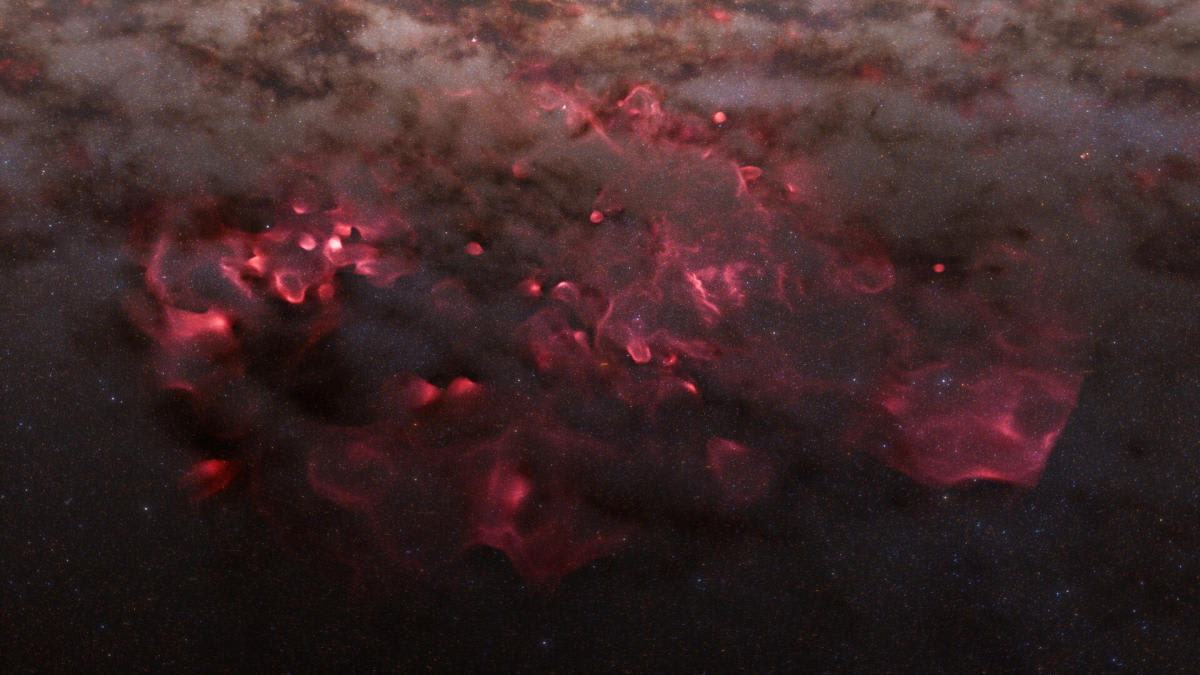

For the study, the scientists targeted the Ophiuchus molecular cloud, 450 light-years away, which has several B-type stars that are young, hot, and emit strong UV radiation. The five objects chosen for the study (published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics) are situated at different distances from these massive stars, according to the Max Planck Institute. “We wanted to take a closer look at protostars, i.e., young stars that are still forming deep inside their parent molecular clouds. As protostars accrete mass, they launch part of it outward in the form of jets,” said Iason Skretas, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute of Radio Astronomy (MPIfR).

These jets are known as outflows and are a visible sign of star formation, the nature of which can be understood by considering the existence of ultraviolet radiation. “This is the first surprise. Young stars are not capable of being a source of radiation; they cannot 'produce' radiation. So we should not expect it. And yet we have shown that UV occurs near protostars. Where did it come from, what is its source: internal or external? We decided to investigate this,” added Dr. Agata Karska of the Center for Modern Inter-disciplinary Technologies at Nicolaus Copernicus University.

The MIRI instrument can observe objects in the wavelength range from 2 to 28 micrometers, covering multiple lines of molecular hydrogen (H2). This cannot be observed from the ground with the Earth’s atmosphere in the way, making the JWST and its ability to spot these lines even from very faint objects with high resolution crucial to a study of this sort. H2 is the most significant molecule in the universe, as it is the most abundant and yet has a structure that is difficult to observe in molecular clouds, given the low temperatures. That being said, young stars produce shockwaves that heat and compress the matter, thereby creating a bright H2 emission.

The analysis revealed the presence of UV radiation around protostars and its impact on the molecular hydrogen. One source of the UV radiation could be the processes taking place around the protostars. This could be shocks from the interactions of the molecular cloud and the protostar or from shocks along the material jet being shot. Another possibility is that the UV radiation is from nearby massive stars, shining their light on protostars. Two methods were used to get an idea of external UV radiation. One relied on the characteristics of the surrounding stars and their distances from the observed sources, while the other depended on the dust that can absorb UV radiation and re-emit at longer wavelenghts.

“Using these two methods, we showed that UV radiation—in terms of external conditions—varies significantly between our protostars, and therefore we should see differences in molecular emission," Skretas said. Since this was not seen, the team was able to reject external elements as the sources of this radiation. "We can say with certainty that UV radiation is present in the vicinity of the protostar, as it undoubtedly affects the observed molecular lines," Karska said. "Therefore, its origin has to be internal," they added. These findings necessitate the inclusion of the production of UV radiation in star-formation models.

More on Starlust

Formation of universe's first stars 13 billion years ago replicated in a groundbreaking simulation