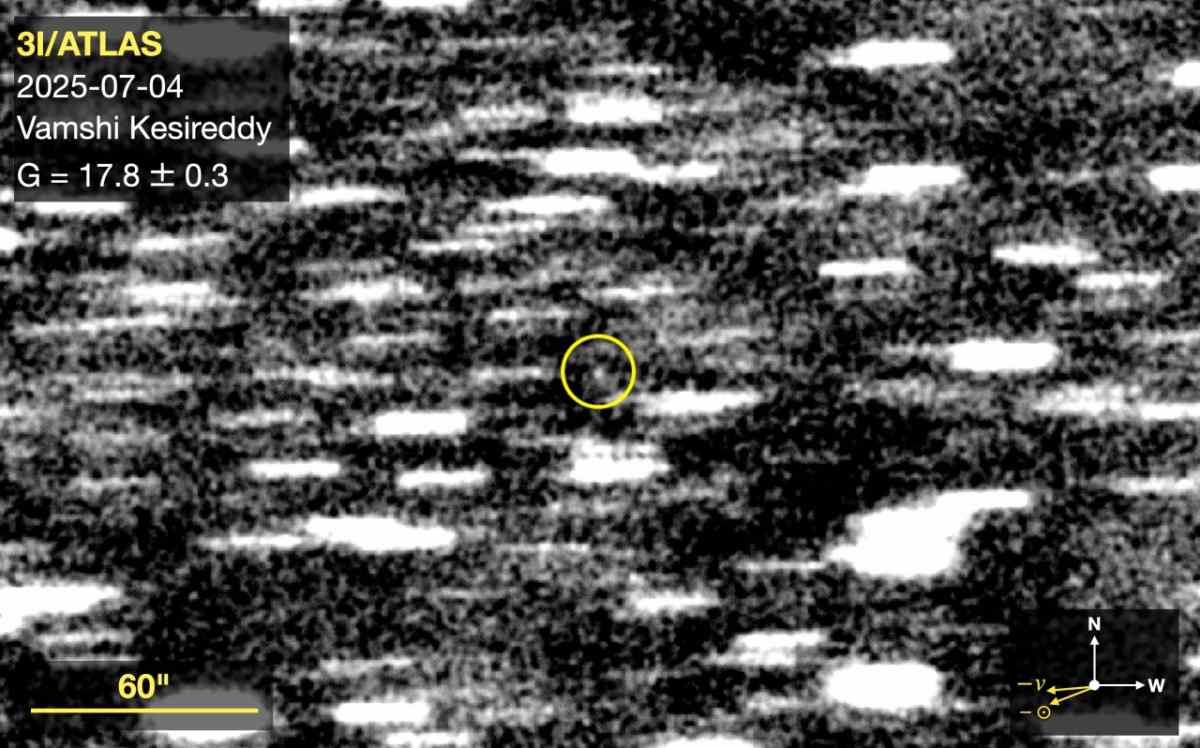

If 3I/ATLAS didn’t break up during perihelion, it may not be a natural comet, says Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb

A recent study by Harvard's Avi Loeb claims that the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS may not be your typical comet. This claim depends on whether future observations of the celestial marvel show that it stayed intact during its closest pass to the Sun, known as perihelion, something Loeb discussed in his blog on Medium.

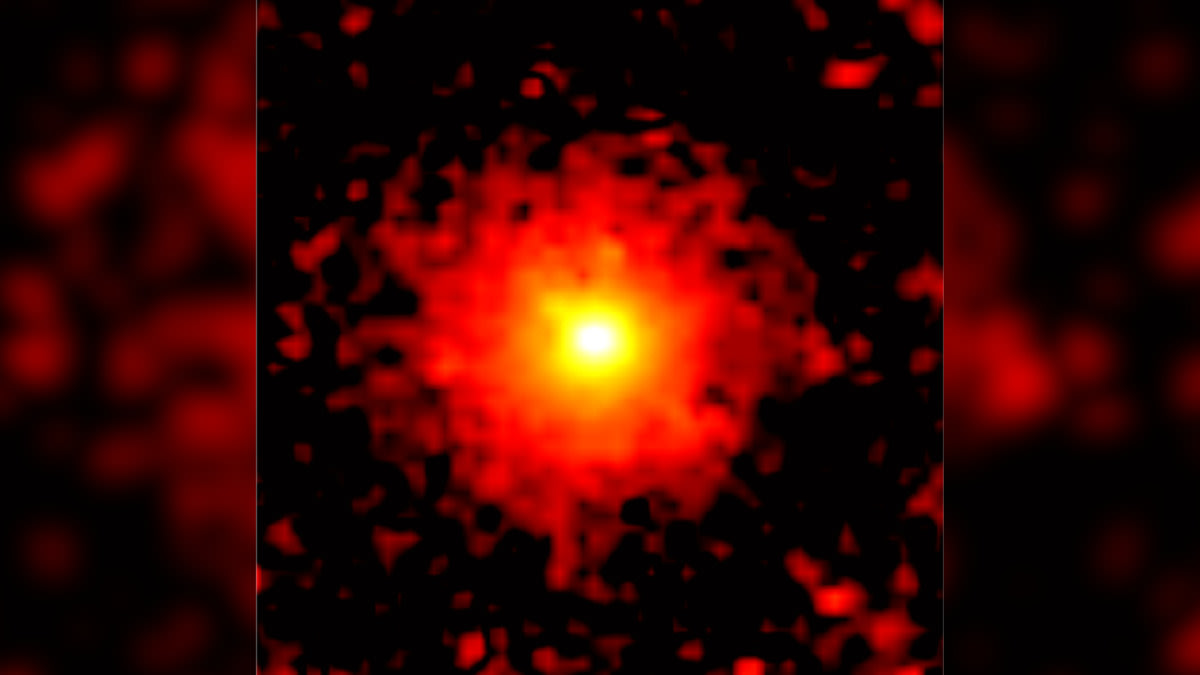

The latest large-scale perihelion image of 3I/ATLAS reported by Michael Buechner and Frank Niebling on November 9 reveals massive jets extending ~1 million km sunward and ~3 million km away from the Sun. Based on Loeb's calculations, the huge outgassing captured in these new images doesn’t quite match what we’d typically expect from a stable, single-body comet. Loeb estimates the total amount of material ejected from 3I/ATLAS during its closest approach to the Sun to be about 16% (around 5 billion tons) of its mass.

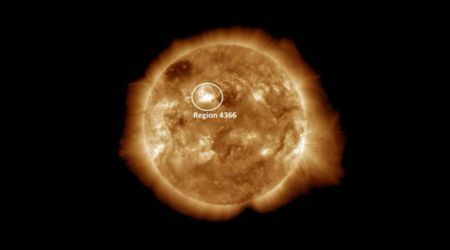

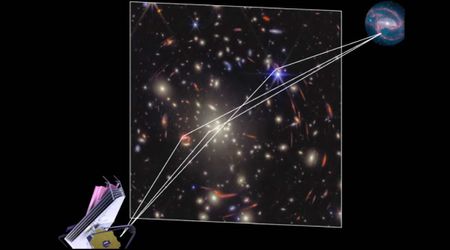

It looks like most of the mass loss is coming from carbon dioxide (CO₂), according to NASA's James Webb Space Telescope data. To make that happen, the Sun would have to heat up a surface area of more than 1,600 square kilometers. That’s roughly the size of a sphere with a diameter of about 23 kilometers, over four times bigger than the maximum of 5.6 kilometers that was estimated based on Hubble Space Telescope images.

![Hubble captured this image of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS on July 21, 2025, when the comet was 277 million miles from Earth. [Image Source: NASA, ESA, David Jewitt (UCLA); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)]](https://de40cj7fpezr7.cloudfront.net/c49eeb4e-e60a-46c0-b39f-68fbb2ee9297.jpeg)

If 3I/ATLAS is just a regular comet, then the huge difference in energy levels must mean it broke apart into several pieces when it got close to the Sun. This kind of dramatic breakup would expose a lot more surface area to solar radiation, at least 16 times more. It makes sense, given how quickly it brightened and lost mass.

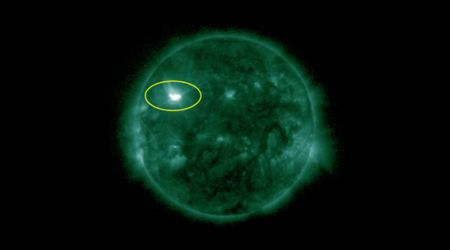

However, Loeb suggests a striking alternative: if future observations show that 3I/ATLAS remains in one piece, then scientists might need to reconsider whether it’s really a natural comet. "If upcoming observations were to reveal that 3I/ATLAS was not decimated by the Sun and maintained its integrity as a single body, then we will have to consider that it is something other than a natural comet," he wrote in his blog. Those jets could actually point to some sort of technological propulsion instead of the usual gradual gas release we see from comets, which typically happens at around 0.4 km/s. If it’s an engineered object, it could be using chemical or ion thrusters to achieve that thrust without needing as much mass, which could help explain this whole mystery around its energy and size. Plus, Loeb highlights some other unusual features of this object, like how its massive size is millions of times greater than the first known interstellar visitor, 'Oumuamua, and the way it’s moving along a path that seems too strange for a random astrophysical object.

3I/ATLAS is really going to be put to the test on December 19, 2025, when it gets closest to Earth. This is a unique opportunity for Hubble, Webb, and ground-based observatories to check if it survives its trip around the Sun. Loeb wrapped up by saying that the upcoming spectroscopic observations will help figure out the speed, mass flow, and makeup of the jets from 3I/ATLAS.

More on Starlust

Massive tail and anti-tail jets reveal unexpected structure of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS