Giant sunspot larger than expected swings to face Earth after unleashing M-class solar flare

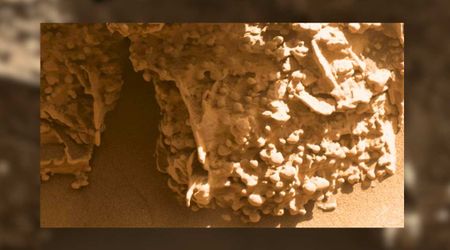

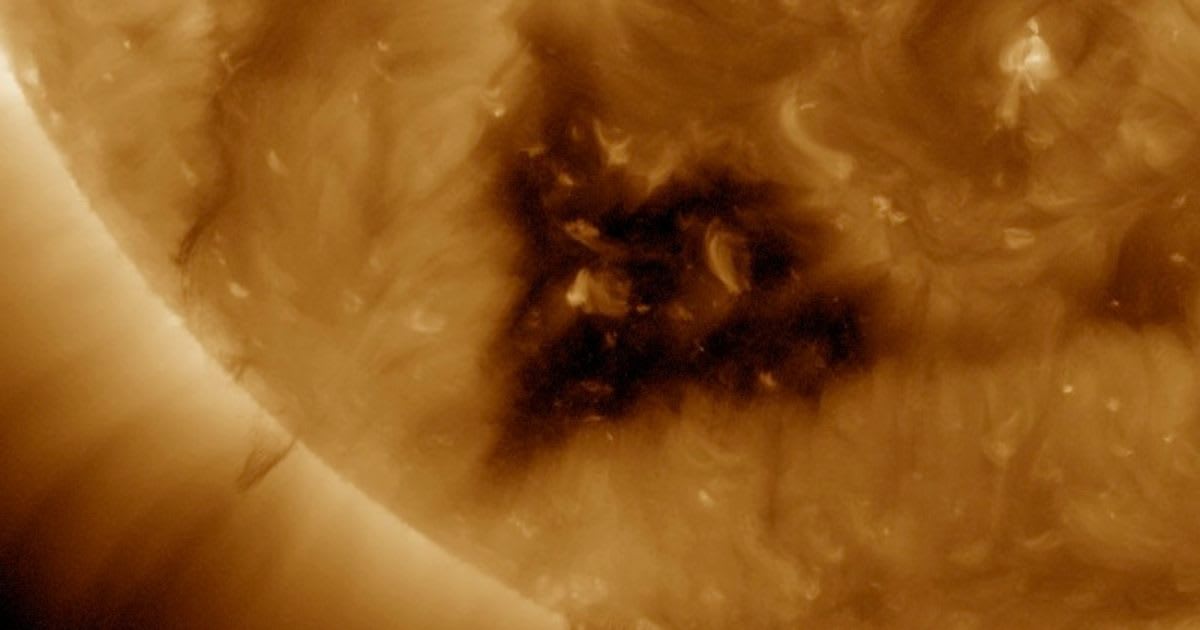

A gigantic sunspot group, larger than forecasters had anticipated, which fired a solar flare as it was turning to face Earth, is now here, according to Space Weather. It came fully into view on November 30, just days after NASA's Perseverance rover spotted it from Mars. Early on, it was labeled as large, but now, the numbers are out. The whole cluster spans about 80,000 miles (130,000 kilometers), with at least four of its dark cores exceeding the Earth's diameter. The scale is such that backyard observers with safe, filtered telescopes can spot the sunspot.

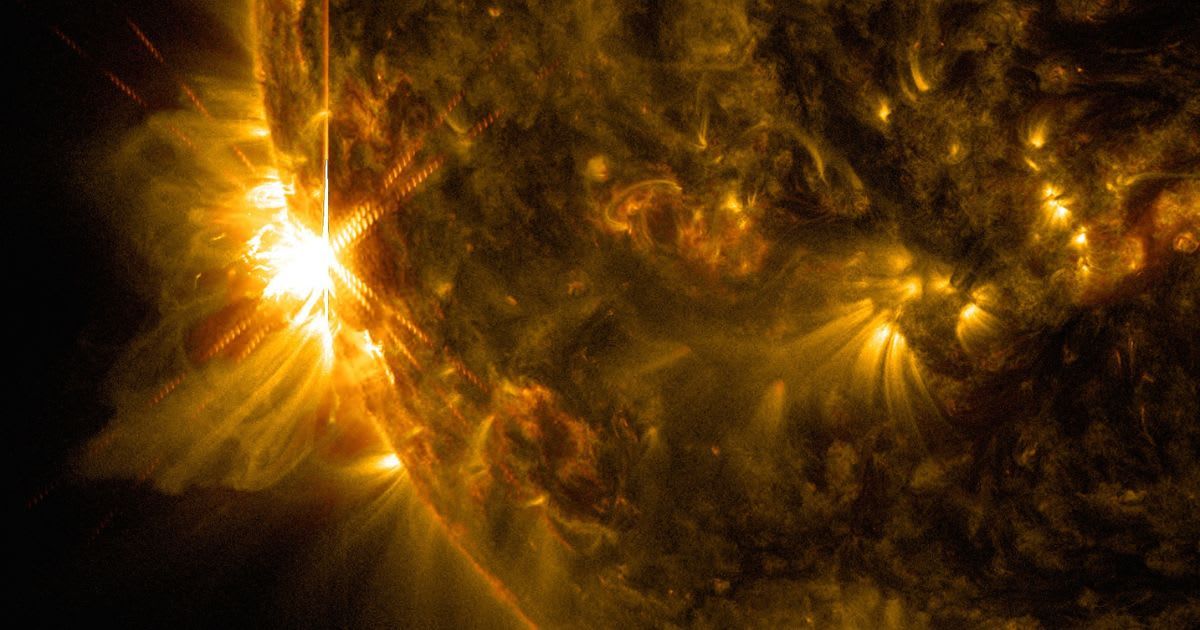

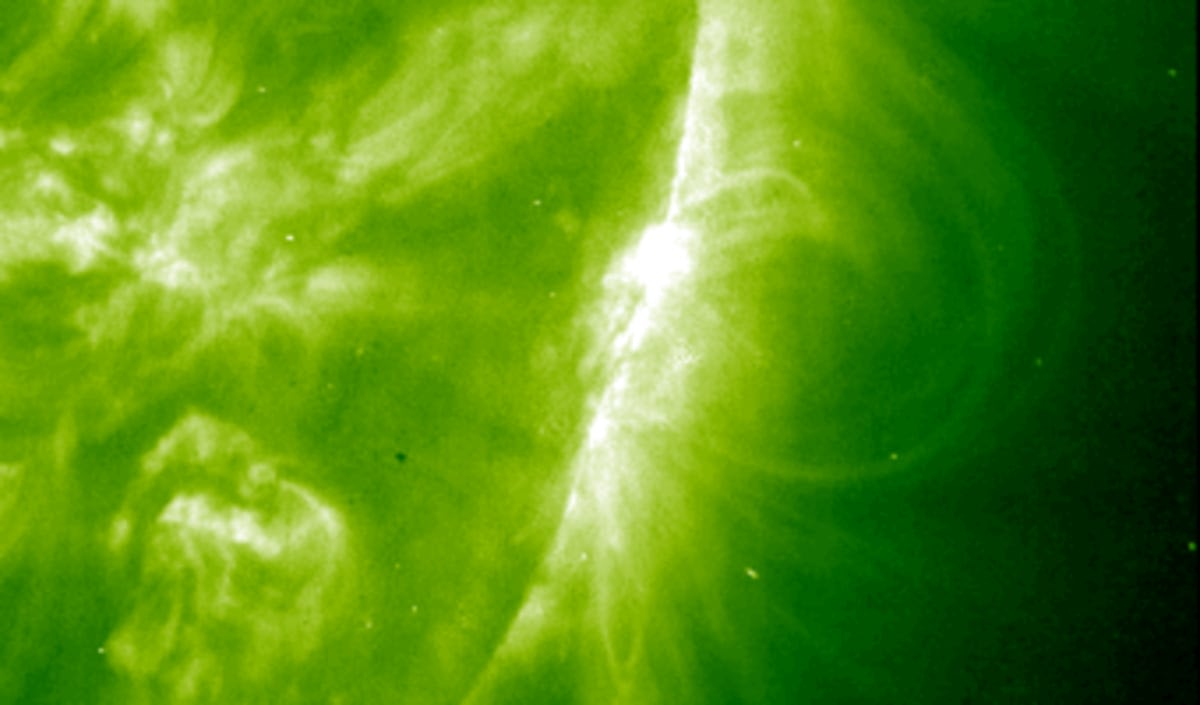

It didn't take long for the sunspot to make its presence known. A moderate M5.9-class solar flare erupted from the sun's newly visible eastern edge late Friday at 22:22 UTC, according to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center. This M-class flare was powerful enough to produce brief, minor radio blackouts on the sunlit side of Earth, classified as an R2-Moderate event. Such disturbances mainly affect HF radio communications used by aviation, maritime, and amateur operators.

Amateur astronomer Andy Devey followed the developing chaos from his observatory near Mojácar, Spain, on November 29, per Space Weather. He captured a nearly three-hour sequence showing the active region as it began to roll around the Sun's eastern edge. "It was sizzling with C-class solar flares," Devey reported, pointing out magnetic turbulence already present around it.

One M6-class flare was detected on November 28, when the sunspot was still partly hidden; this suggests the blast could have been even more powerful, an X-class event. According to Space Weather, now that the enormous, highly active region is Earth-facing, any future, more powerful flares will be considered geoeffective, that is, they have the potential to directly impact our planet's space environment.

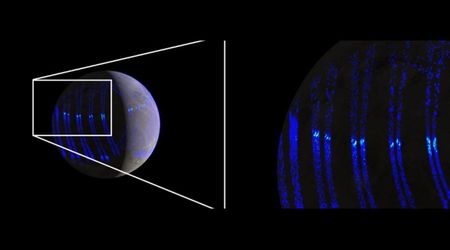

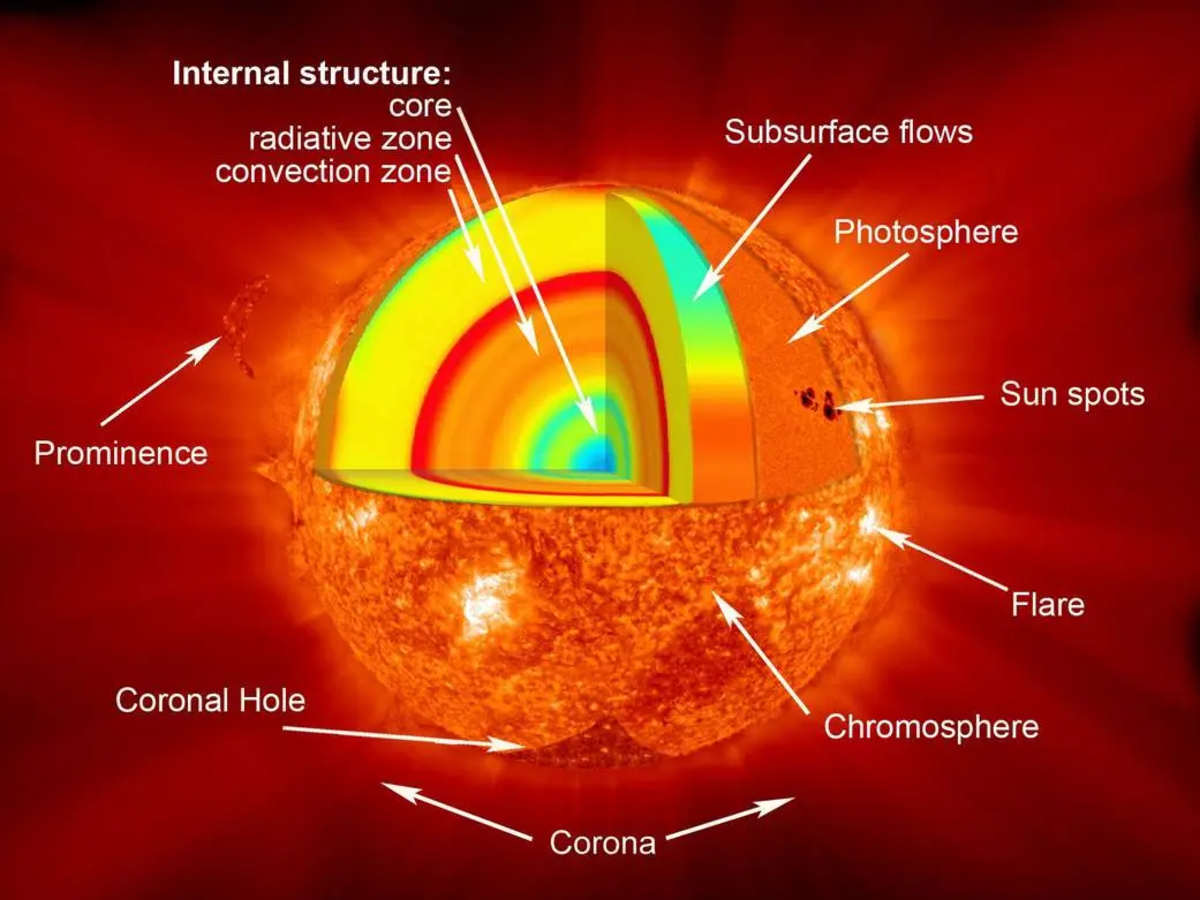

Meanwhile, while this giant sunspot group is pounding Earth from a distance, scientists have also managed to crack part of the mystery concerning the Sun's magnetic engine. A University of California, Santa Cruz, team has produced the first reliable models of the forces at work in the tachocline, that thin, vital layer deep inside the Sun. The work, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, represents a major advancement in understanding how the Sun's magnetic field is produced by its interior.

The tachocline is a narrow transitional zone, first detected by helioseismology decades ago, where the rigidly rotating core meets the more fluid, convective layer. For years, scientists had suspected that this small region drives the solar dynamo responsible for the Sun's enormous magnetic field, but it was extraordinarily difficult to build precise simulations of its complex interactions.

Led by UCSC postdoctoral researcher Loren Matilsky, the team finally overcame that challenge. Running for millions of hours on NASA's most powerful supercomputer, their "hero" calculations accurately prioritized and simulated the crucial physical processes occurring inside the Sun. In what was a first, the simulations resulted in the spontaneous formation of a tachocline, despite not being specifically programmed for the task. The models demonstrated that the magnetic forces that the solar dynamo gives rise to are likely responsible for maintaining the tachocline's narrowness.

More on Starlust

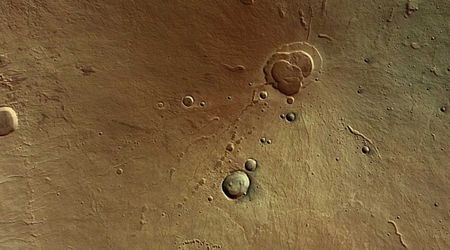

NASA's Perseverance rover detects giant sunspot 15 times wider than Earth rotating toward our planet

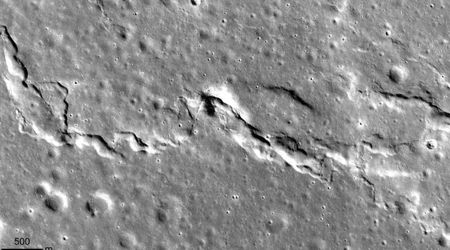

Scientists solve 50-year-old mystery, discover solar flares 6.5 times hotter than expected