ESA's Solar Orbiter captures unprecedented view of magnetic avalanche on Sun

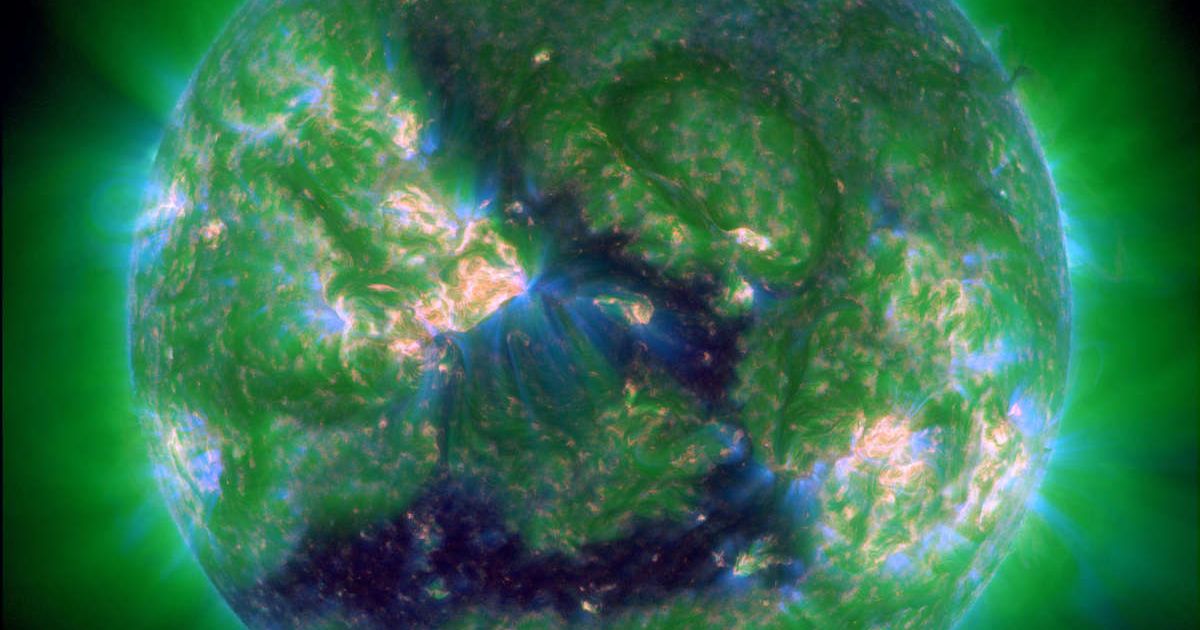

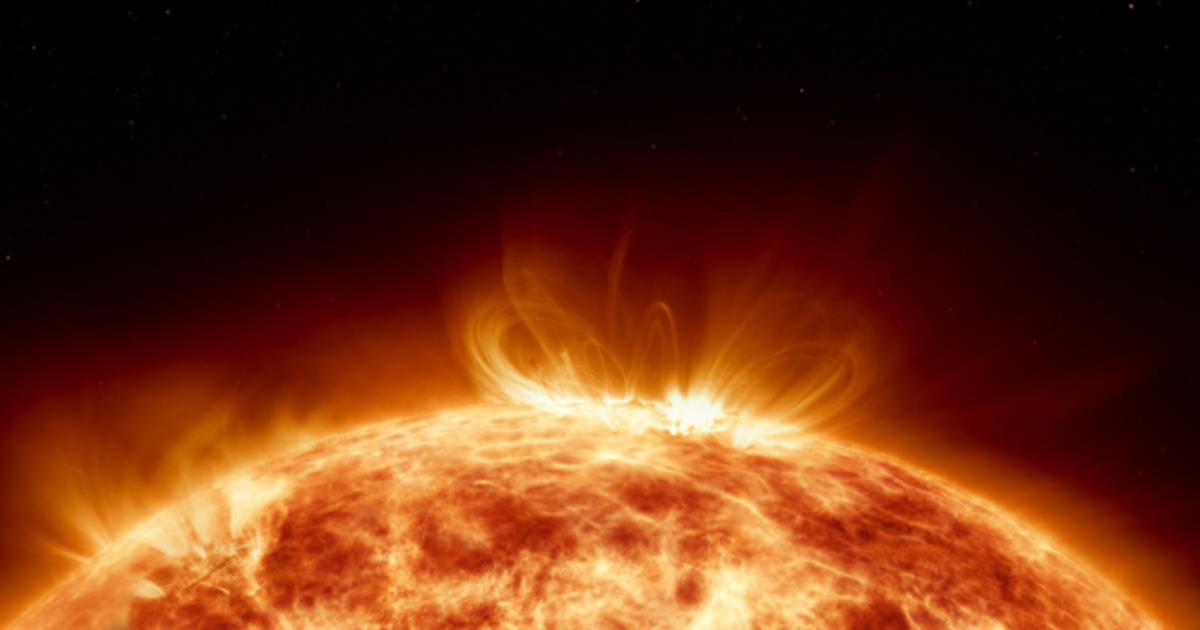

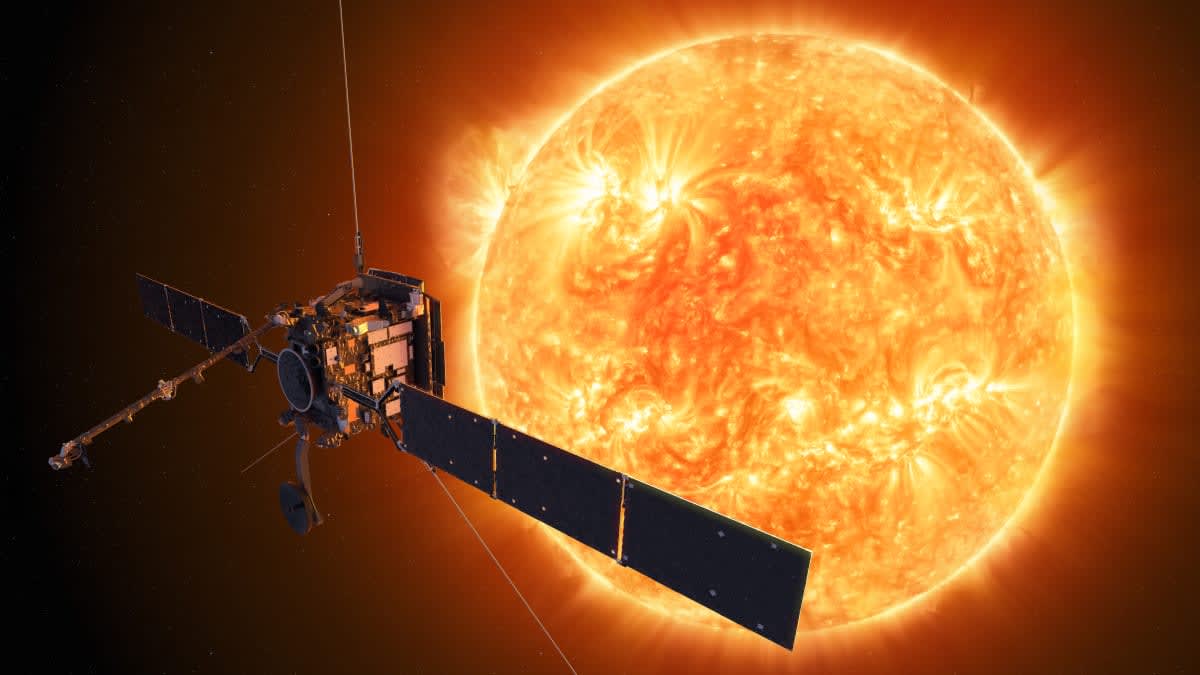

The Sun constantly radiates energy, occasionally going into overdrive, triggering violent eruptions called solar flares. A new study using ultra-sharp observations from the European Space Agency's (ESA) Solar Orbiter spacecraft suggests that these flares may not be triggered by just one disturbance—but several tiny ones, cascading together in what researchers call a magnetic avalanche. One such avalanche took place on September 30, 2024, and the spacecraft’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) photographed it.

The spacecraft parked itself 45 million kilometers away from the star and achieved this astonishing feat, allowing a team of scientists to watch the star’s energetic outburst. They report the observations in a paper published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. At the heart of solar flares lies magnetic reconnection—a process where magnetic field lines snap, reconnect, and release stored energy as heat, plasma, and high-energy particles. While the finer details of this process are not yet fully understood, the Solar Orbiter's observation was a huge step in the right direction.

As the EUI focused on features spanning 210 kilometers across the corona (the outer atmosphere), clicking fluctuations every couple of seconds, the SPICE, STIX, and PHI instruments looked as far down as the photosphere (the Sun's visible surface). About 40 minutes ahead of the flare, the EUI images revealed a loop of dark plasma reaching far into the million-degree outer atmosphere, held by twisted, arc-like lines of magnetic field. Such an arrangement results in the buildup of massive energy.

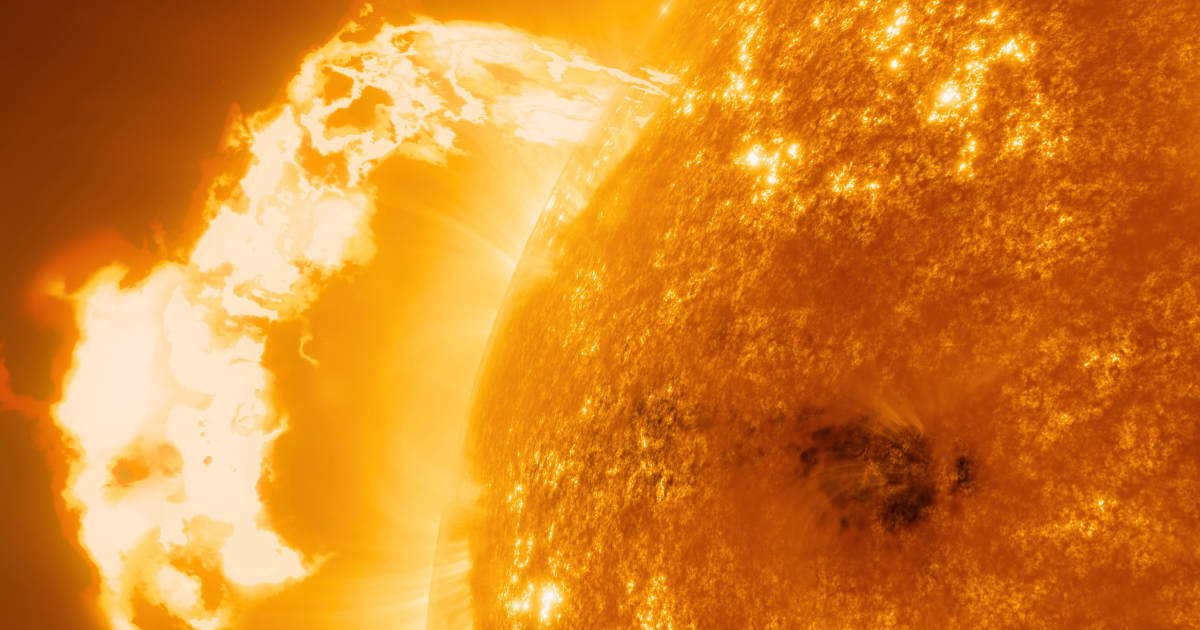

Then, at 11:47 p.m., a discharge occurred, with the plasma structure uncoiling explosively and releasing charged particles at 40 to 50 percent the speed of light. "It was extremely fortunate that Solar Orbiter, the most powerful solar observatory in space, was looking at the flare at exactly the right time and from exactly the right angle. It’s impossible to plan something like this days in advance," said Lakshmi Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and lead author of the study, in a statement. Next to the dark plasma loop were knots of arc-like bright plasma streams bound within the magnetic field. About 30 minutes before the eruption, these knots started to break open and rearrange themselves. More such knots began to form every second, undergoing their own reconnection processes, until the larger plasma loop broke open and the flare peaked.

These minutes before the flare are extremely important, and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began,” Chitta said. “We were surprised by how the large flare is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that spread rapidly in space and time.” This is proof that not all the energy is released into space with the initial flare and that some of it is stored in the surrounding plasma and released as "plasma blobs." "This study is one of the most exciting results from Solar Orbiter so far,” said ESA’s Solar Orbiter co-Project Scientist Miho Janvier. “An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars.”

More on Starlust

Aurora alert: One of the fastest solar storms in decades just hit Earth, triggering severe G4 storm

Earth just faced the strongest solar radiation storm in over 22 years—here's what you need to know