A gamma-ray burst raged on for seven hours. A researcher, who was behind its discovery, explains how.

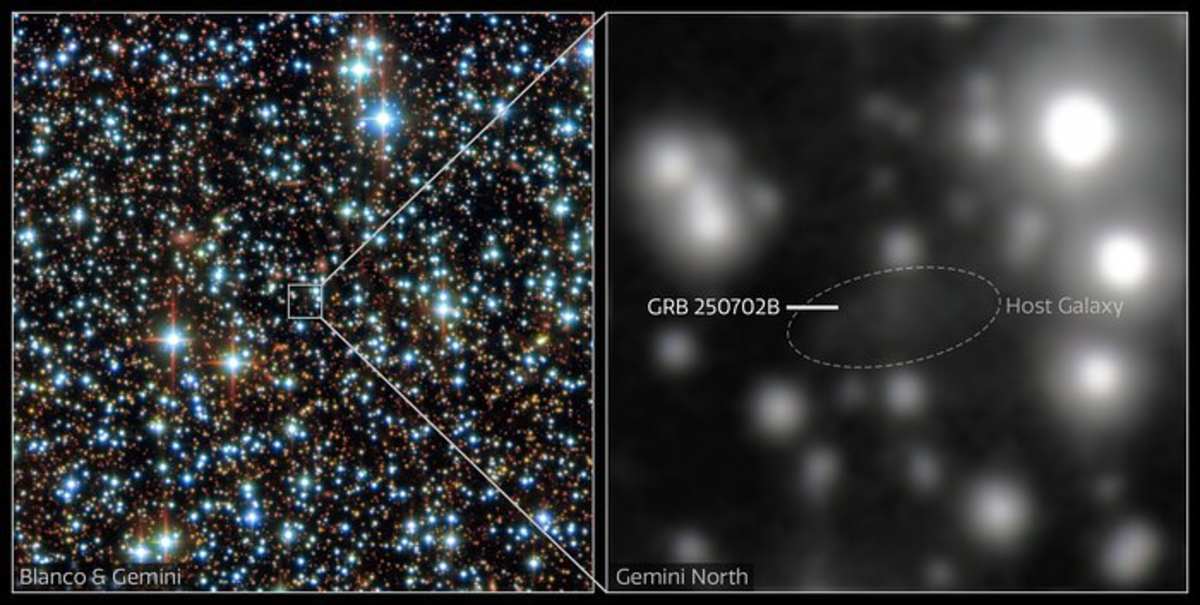

A key member behind the discovery of GRB 250702B has shared their insights into the longest gamma-ray burst ever recorded, which blazed for seven hours in 2025 and baffled scientists due to its atypical nature. In a recent interview with BBC Sky at Night Magazine, Eliza Neights, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, explained the unusual mechanism that lies behind this never-before-seen event, proposing that a “helium merger” is the key process to this observation. This development follows on from last year’s detection and offers an explanation in more accessible terms via the interview for why the burst lasted 25,000 seconds, far exceeding typical GRBs that fade much earlier, with the previous record-holder lasting 15,000 seconds.

Neights, serving as a “burst advocate” for NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Burst Monitor, had previously detailed her research findings in the paper she co-authored, which was published on November 14, 2025. On being asked how and what it was that she had discovered, Neights replied, “I was on duty at the time the instrument detected its very unusual pattern: three gamma-ray bursts that appeared to be coming from the same place in the sky.”

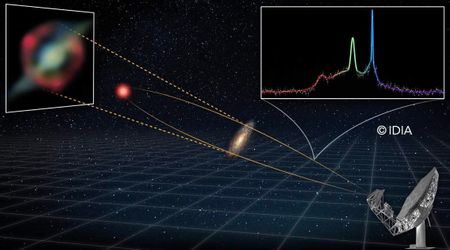

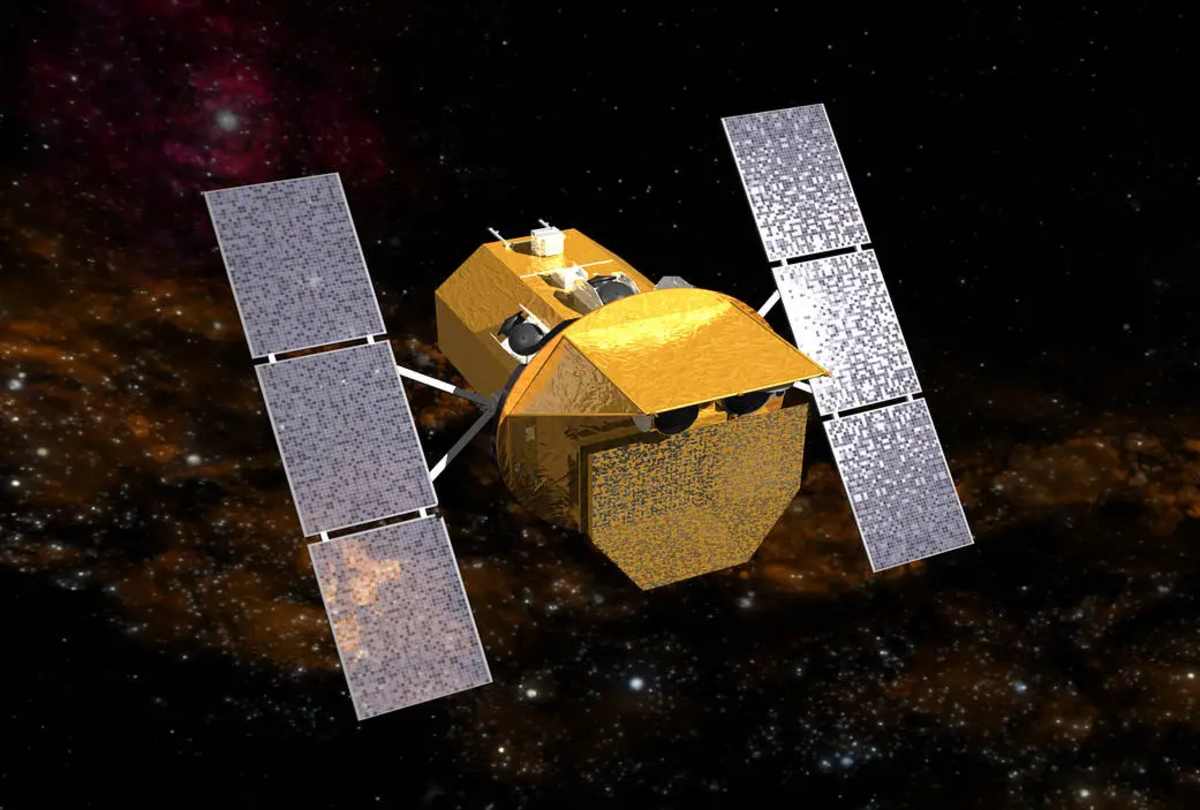

Neights went on to describe the technological backbone of GRB detection in her interview, putting stress on the reliance upon space-based instruments due to the elusiveness and distances of the deep sky objects being dealt with. “Primarily, we use widefield, high-energy monitoring, typically with space telescopes that see a very large part of the sky at a time,” she stated, explaining how these telescopes continuously scan for bright pulses against background noise. Other space-based telescopes that study GRBs through X-rays and gamma rays include NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory and the Einstein Probe by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the European Space Agency (ESA).

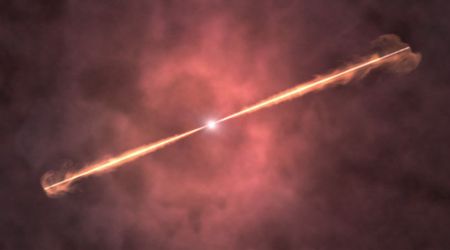

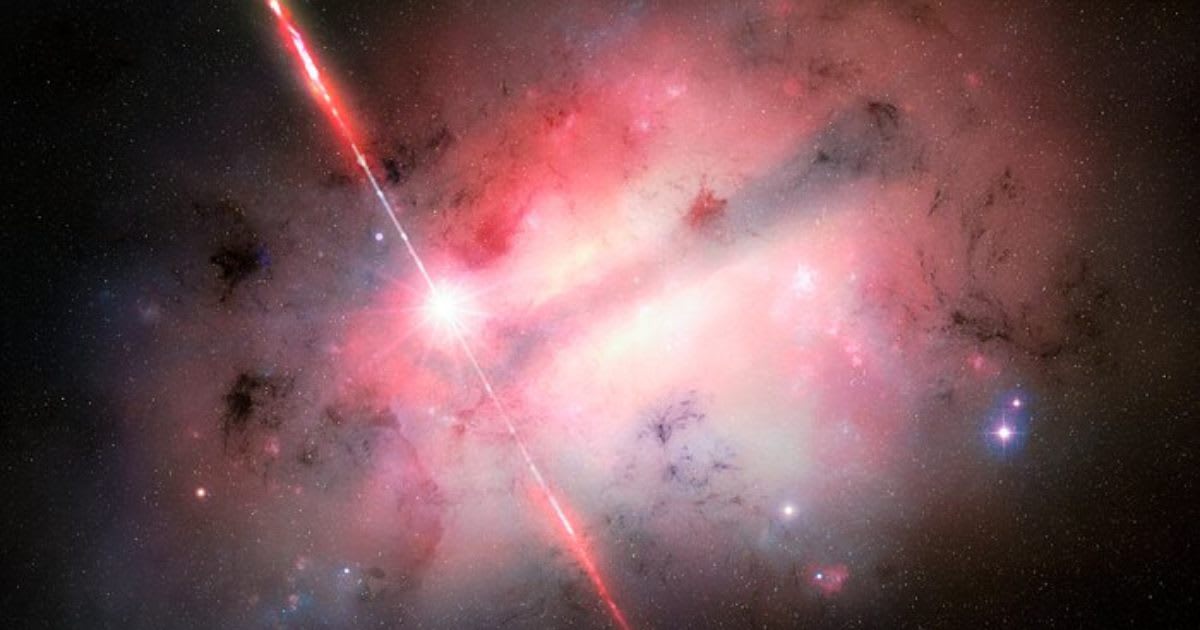

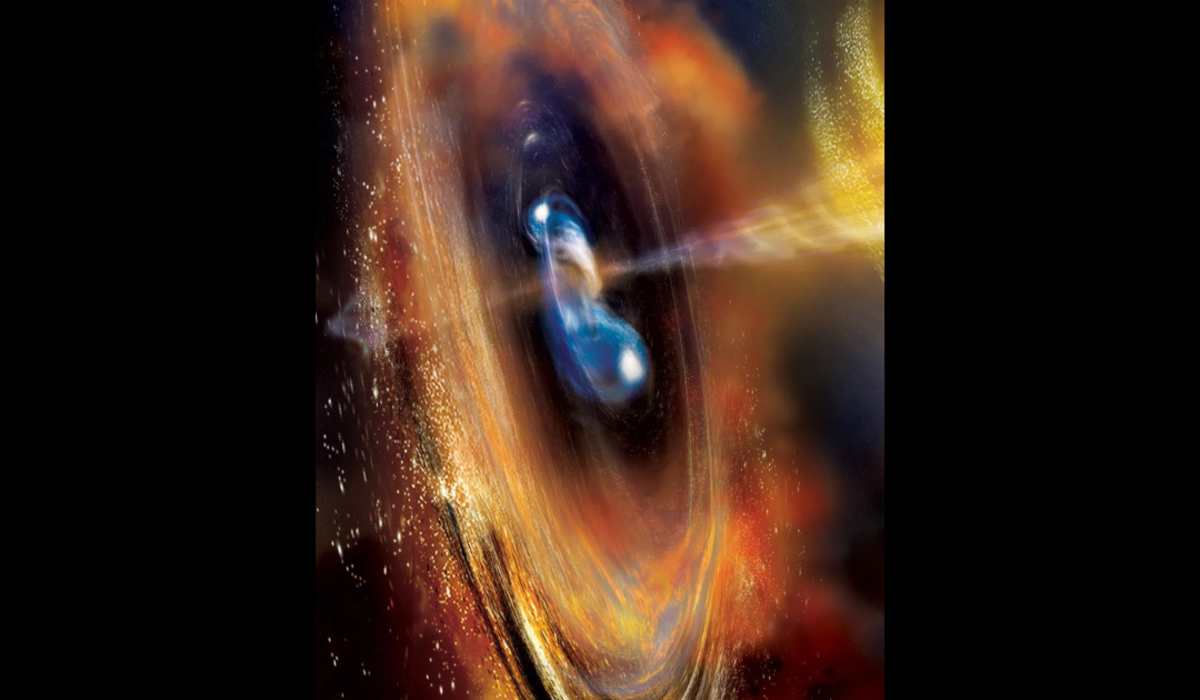

Speaking on how and why GRBs occur, Neights responded, “There are two processes that are known to lead to GRBs. Most originate from the collapse of a rapidly rotating, massive star. These stars collapse into compact objects, probably black holes, which form powerful jets. We detect these jets as gamma-ray bursts when they happen to point towards us. Some other GRBs occur when two neutron stars, very dense stellar remnants, are orbiting each other and then merge. Once again, a compact object forms that produces jets which we can detect.”

However, GRB 250702B’s prolonged burst, high energy, and rapid variability ruled out these scenarios, with the so-called “helium merger” model being reported last year to be the reason for this particular burst. In this model, a stellar-mass black hole orbits a helium star, i.e., one stripped of its hydrogen exteriors, and plunges inside as the star expands, consuming it from within. “When they expand, the orbiting black hole will end up inside the stellar envelope and consume the star rapidly. Suddenly, you have all of this angular momentum being transferred into the black hole, which can give rise to a jet that lasts a long time.” She also mentioned how such rare events evade easy detection because they are dimmer and longer than the short and bright bursts telescopes are designed to detect.

As for what her immediate future holds, Neights informed of her involvement with the Compton Spectrometer and Imager (COSI) telescope, which is understood to launch next year, so as to shed further light on events that eject gamma rays.

More on Starlust

A black hole belching out the remains of a star it ate is emitting more energy than the 'Death Star'

James Webb Space Telescope detects surprising abundance of organic molecules in nearby galaxy