UC Berkeley's crowdsourced project helped narrow down search for extraterrestrial life to 100 signals

For more than two decades, millions of ordinary people turned their home computers into high-powered research tools for one of the most ambitious experiments in history. Now, scientists at UC Berkeley have announced they have distilled 21 years of data into a "shortlist" of 100 mysterious radio signals that merit further investigation.

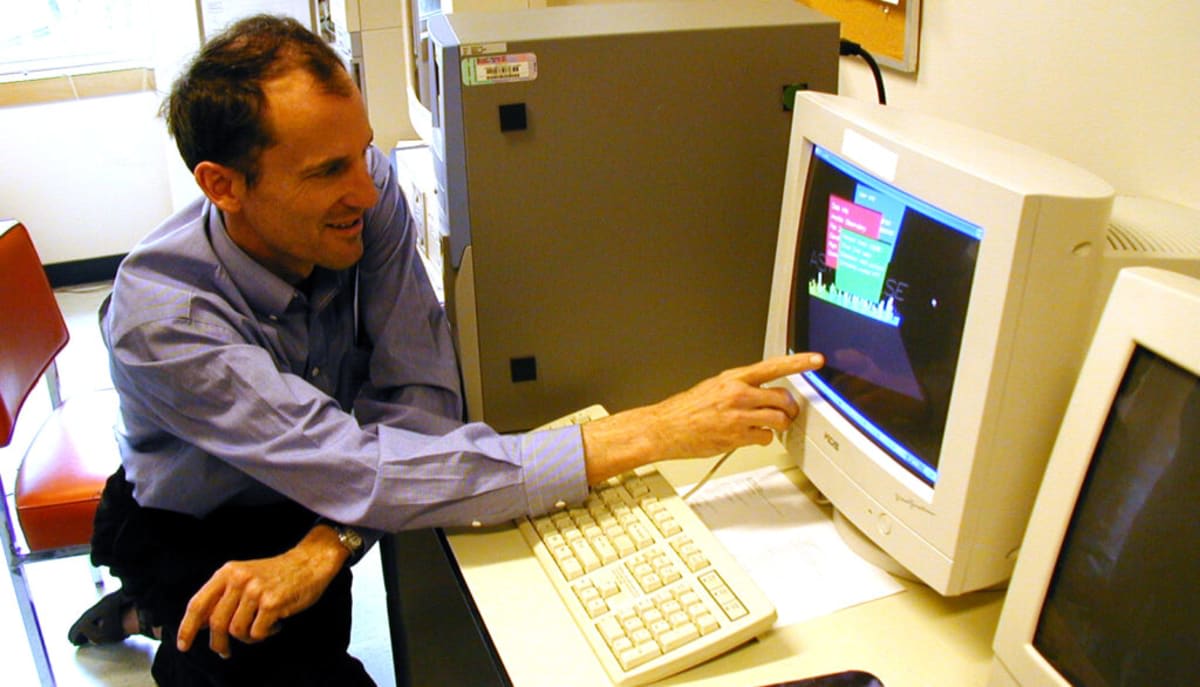

The SETI@home project launched in 1999, during the nascent days of the internet. Volunteers could download the SETI@home software on their personal computers and have it analyze the data captured by the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico for unusual signals indicative of advanced civilizations in our galaxy. What began as a Quixotic niche experiment very quickly evolved into a global phenomenon, netting more than two million users who collectively detected 12 billion energy blips. After a decade of rigorous analysis, the billions of detections have finally been filtered down to 100 prime candidates. Since last July, the team has been using China's massive Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, to revisit those specific points in the sky. While the FAST data is yet to be analyzed, David Anderson, the project's co-founder and a computer scientist at UC Berkeley, thinks that the chances of finding extraterrestrial civilizations are slim. That being said, he also thinks that the journey itself has been a scientific triumph.

“When we were designing SETI@home, we tried to decide whether it was worth doing, whether we’d get enough computing power to actually do new science. Our calculations were based on getting 50,000 volunteers. Pretty quickly, we had a million volunteers,” said Anderson in a statement. “It was kind of cool, and I would like to let that community and the world know that we actually did some science.” The search for an extraterrestrial beacon is complicated by the "noise" of modern life. Everything from orbiting satellites to kitchen microwaves can create interference that looks like a signal from deep space. To address this hurdle, the team inserted 3,000 fake signals, which they nicknamed "birdies," into the data before filtering it in order to eliminate the RFI and noise. By keeping themselves oblivious to the nature of these signals, they were able to test their sensitivity using the signal strengths of the birdies they could detect.

Project director Eric Korpela explained that for an ET beacon to be detected, it would have to be around the radio wavelength of 21 centimeters—a frequency at which astronomers scan the universe. Unfortunately, no ET narrowband signal has been detected so far. That being said, the results of the project presented in the two papers (here and here) in The Astrophysical Journal have lessons for ongoing and future searches. "If we don’t find ET, what we can say is that we established a new sensitivity level," Anderson said.

The SETI@home project was unique in that it scanned most of the stars in the Milky Way, whereas most current SETI searches, including the Breakthrough Listen Project, concentrate on particular stars known to have planets. “We are, without doubt, the most sensitive narrow-band search of large portions of the sky, so we had the best chance of finding something," Korpela added. "So yeah, there’s a little disappointment that we didn’t see anything."

Despite his disappointment, however, Korpela thinks that a similar crowdsourced SETI project is feasible even today. After all, the computers and the internet today are much faster than they used to be when the project started. "I think that you could still get significantly more processing power than we used for SETI@home and process more data because of a wider internet bandwidth," he said. But a project of such scale would require personnel, and they would need to be paid. Of the six people who once operated SETI@home, Korpela is the only paid member now. He says that if he had the money, he would reanalyze the radio data right away. "There’s still the potential that ET is in that data and we missed it just by a hair."

More on Starlust

Earth’s radio signals highlight regions where extraterrestrial life could find us