The first alien civilization we find might already be nearing its end

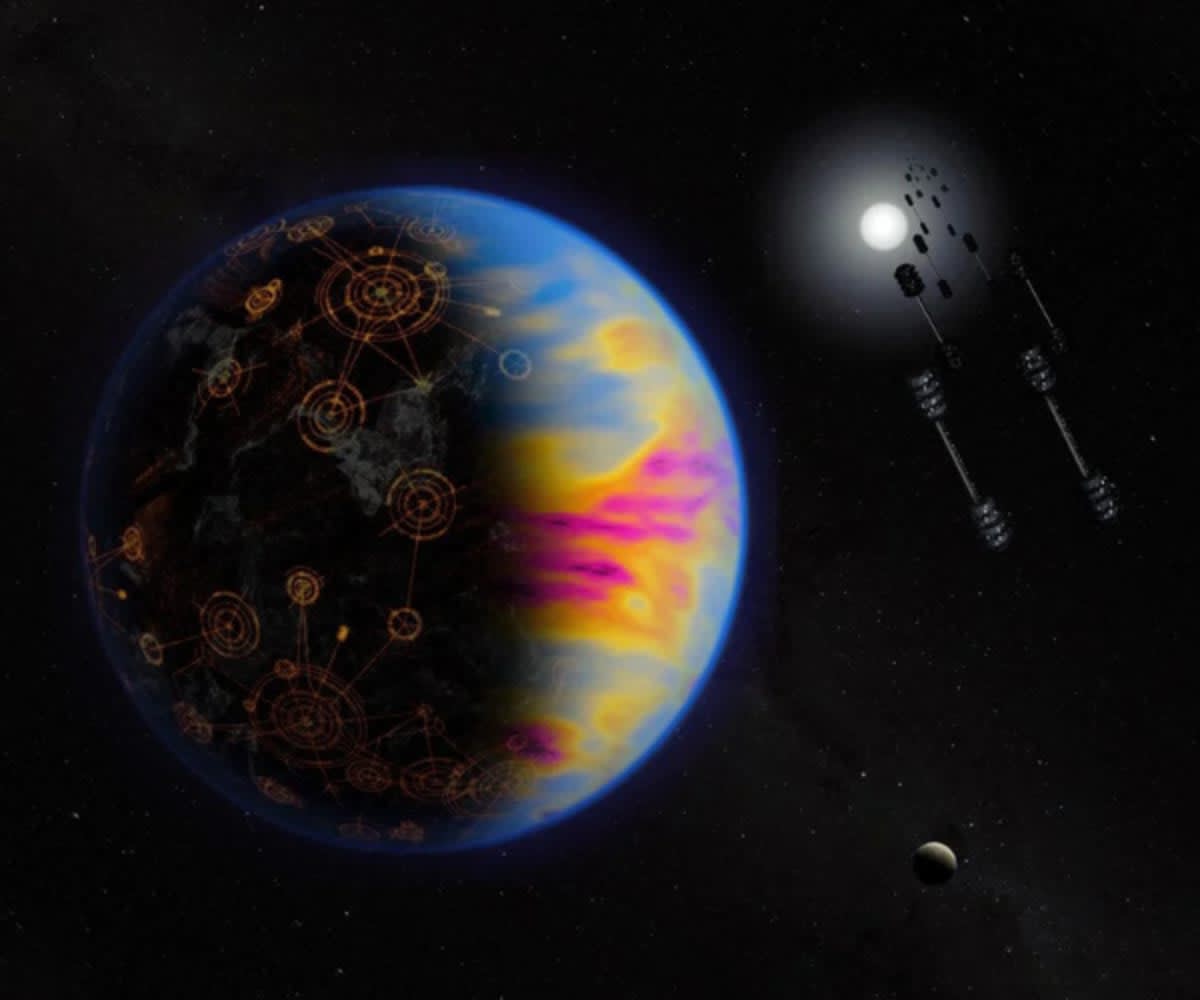

When people imagine discovering alien life, they often picture a calm, advanced civilization quietly sending a polite signal across the stars. But a Columbia University astronomer thinks our first confirmed encounter with extraterrestrial technology could be far louder and far stranger. In a new research paper, David Kipping, director of the Cool Worlds Lab at Columbia University, introduces what he calls "The Eschatian Hypothesis." The idea is simple but unsettling. The first alien civilization humanity detects is unlikely to be a typical, stable one. Instead, it may be an extreme, short-lived, and unusually “loud” example that stands out.

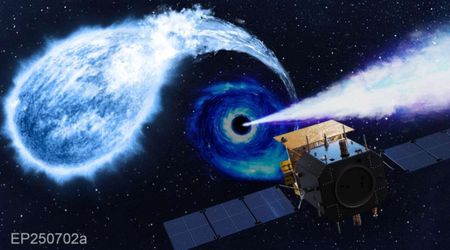

Kipping’s thinking is shaped by a long history of observational bias in astronomy. As he notes, “The history of astronomical discovery shows that many of the most detectable phenomena, especially detection firsts, are not typical members of their broader class, but rather rare, extreme cases with disproportionately large observational signatures.” This kind of thing has happened before. The very first exoplanets scientists confirmed weren’t found around stars like our Sun at all, but around a pulsar, a neutron star emitting pulses of radiation at regular intervals. At the time, it surprised many researchers and even made some skeptical. We now know planets around pulsars are extremely rare.

They showed up first simply because they were easier to spot. As Kipping explains, unusual objects often dominate early discoveries, not because they are common, but because they are obvious. He believes the search for extraterrestrial intelligence may follow the same path. Quiet civilizations that operate sustainably over long periods may exist in large numbers, but they would be difficult to spot. Loud civilizations, on the other hand, could briefly flood space with detectable energy.

“If history is any guide,” Kipping writes, “then perhaps the first signatures of extraterrestrial intelligence will too be highly atypical, ‘loud’ examples of their broader class.” And what does "loud” mean in this context? Not sound, but energy—powerful technosignatures that dramatically depart from natural cosmic equilibrium. Kipping points out that many of the brightest events we see in space, such as giant stars and supernovae, are both rare and short-lived. They are visible precisely because they are unstable.

The same may be true for technological civilizations. As Kipping notes, “For a civilization comparable to our own, the brightest luminosity we could achieve would be a global nuclear war, which too is obviously unsustainable.” While extreme, the example highlights a broader point. The most detectable signals may come from moments of crisis rather than long-term success.

Kipping suggests that if a civilization is “loud” for only a tiny slice of its existence, it could still be the one we notice first, as long as it puts out enough energy during that brief window. In one scenario, a civilization loud for just 10⁻⁶ of its lifetime would need to release about one percent of all the energy it ever produces to really stand out.

The Eschatian Hypothesis suggests that “wide-field, high-cadence surveys optimized for generic transients may offer our best chance of detecting such loud, short-lived civilizations.” If the Eschatian Hypothesis is right, the first aliens that humans come across may not be part of a quietly thriving civilization. They may be brief, brilliant flashes of technological activity, loud enough to be seen across the galaxy but fleeting enough to vanish almost as soon as they appear.

More on Starlust

Even if aliens exist in our galaxy, they are probably about 33,000 light-years away: Researchers