Stunning new study claims Mars may have supported life longer than initially suspected

A study published in Nature Communications last year suggested that Mars’ magnetic field may have lasted until about 3.9 billion years ago, rather than ending 4.1 billion years ago. The updated timeline meant that the presence of the magnetic field overlapped with the era when Mars was covered in water, potentially giving life a chance to emerge. Now, another study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research—Planets in November 2025 has found evidence suggesting that Mars may have sustained life longer than previously suspected, thanks to the presence of subsurface water.

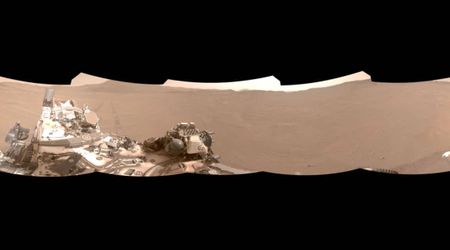

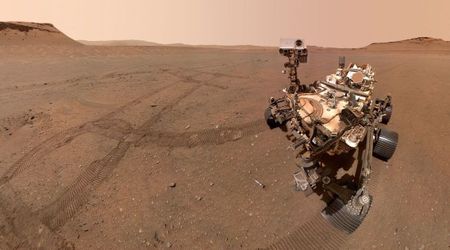

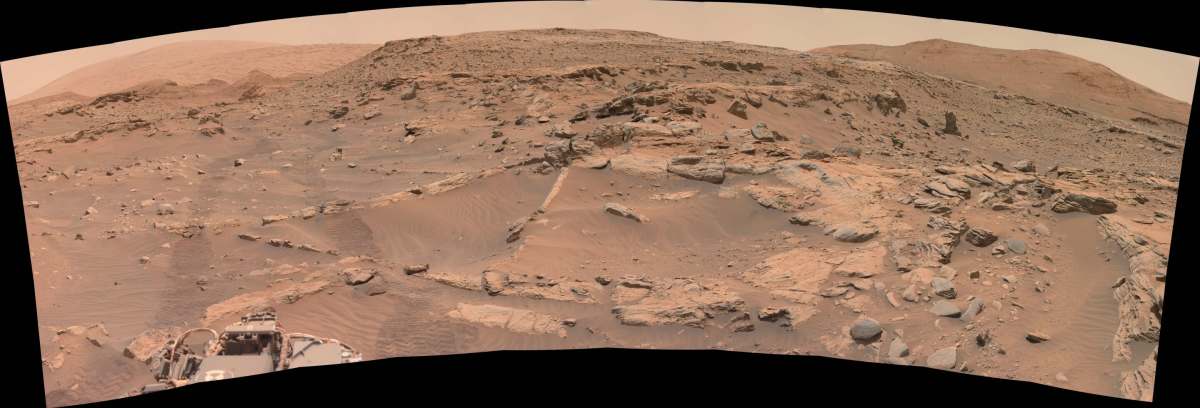

The study shows that ancient sand dunes in Gale Crater, explored by NASA’s Curiosity rover, gradually turned into rock after coming in contact with underground water billions of years ago. “Our findings show that Mars didn’t simply go from wet to dry,” said Dimitra Atri, the principal investigator at New York University Abu Dhabi’s Space Exploration Laboratory. “Even after its lakes and rivers disappeared, small amounts of water continued to move underground, creating protected environments that could have supported microscopic life.”

Per the press release from NYUD, Atri, research assistant Vignesh Krishnamoorthy, and team did a comparative study of the data from Curiosity and that from rock formations in the UAE desert that formed under similar conditions on Earth. Results showed that water from a Martian mountain located close by made its way into the dunes via tiny cracks, soaking the sand from below and leaving behind minerals such as gypsum, which is also the mineral found in the deserts on our planet. With the ability to trap and preserve traces of organic material, these minerals could prove to be crucial in determining how the Red Planet evolved over epochs and highlight how subsurface environments could potentially bear signs of ancient life.

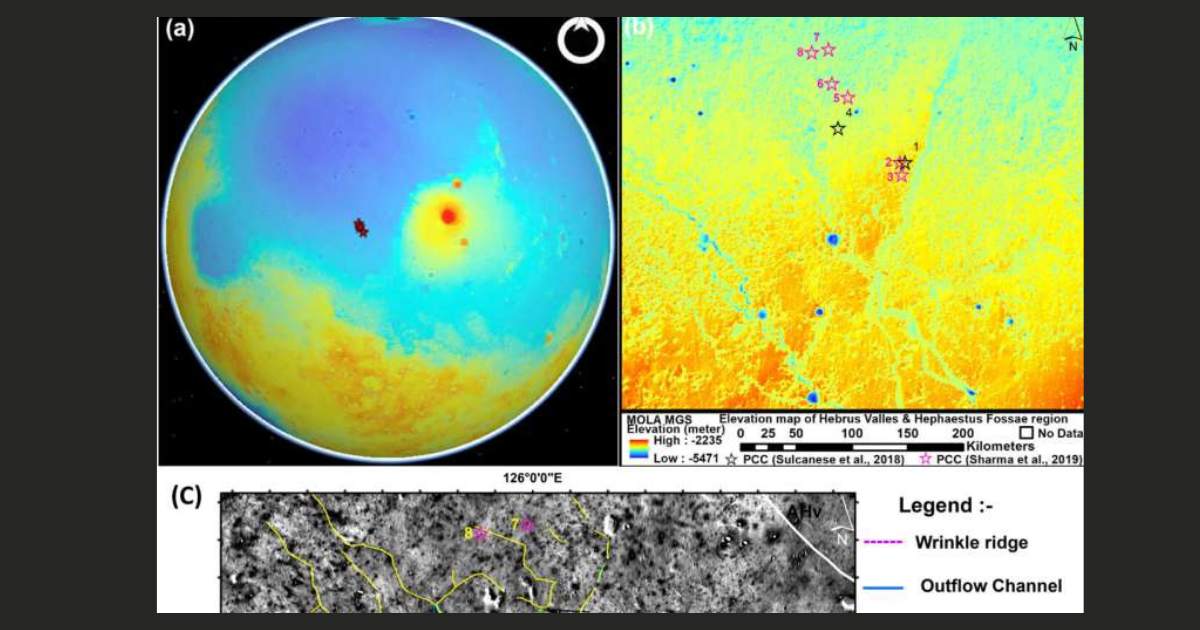

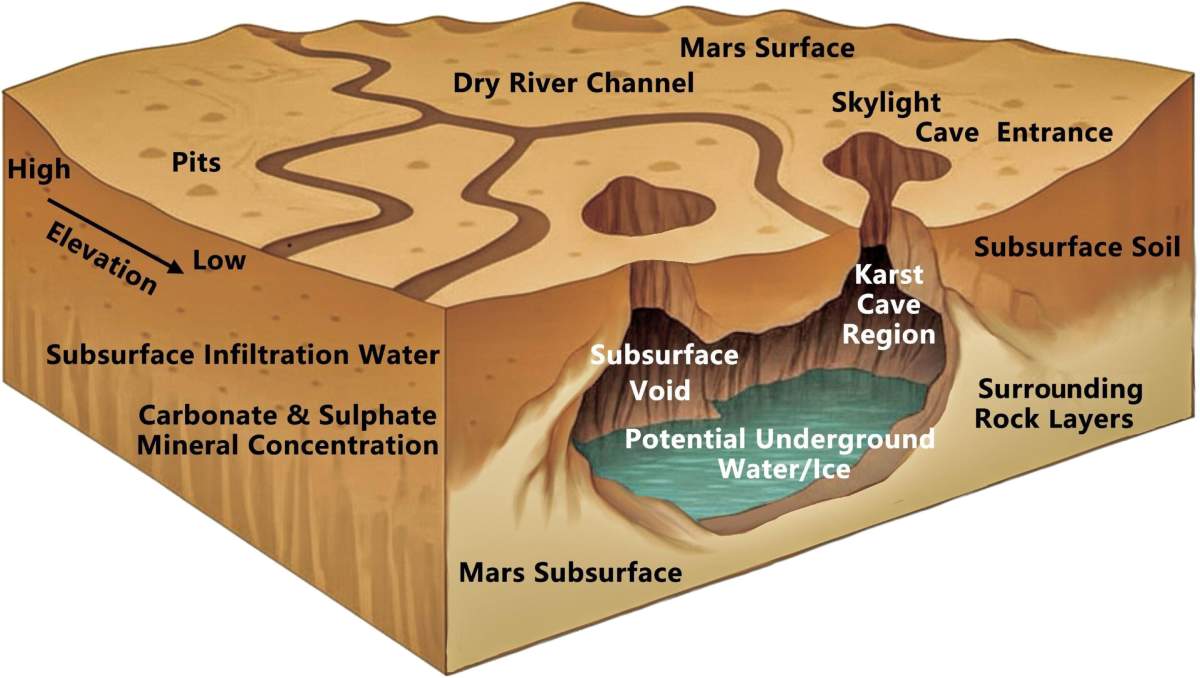

In their paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Chenyu Ding at Shenzhen University, China, and team presented the first evidence of karstic caves on Mars. Thus far, the majority of Martian caves discovered have been lava tubes. However, according to the researchers, the newly discovered ones represent “collapse entrances formed through the dissolution of water-soluble lithologies—defining a new cave-forming class distinct from all previously reported volcanic and tectonic skylights.”

Unlike impact craters that are usually surrounded by raised rims and ejected debris around them, these caves, located in the Hebrus Valles, eight pits in a northwestern region mapped by previous Mars missions, are deep and predominantly circular depressions, indicating that they may have been formed when ancient Martian water dissolved carbonate- and sulfate-laden rocks on the crust. It’s a process not too different from the formation of karstic caves here on Earth.

The researchers concluded this when they found that the rocks surrounding the pits are, in fact, rich in carbonates and sulfates by examining the data taken from the Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) onboard NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor.

As a result, these eight possible karstic caves could be high-priority targets for future robotic or human missions aiming to look for traces of life on Mars. And even if no life is found there, they could serve as natural shelters protecting astronauts from the harsh conditions on the Red Planet.

More on Starlust

ESA’s ExoMars captures massive dust avalanches on Mars triggered by a meteoroid impact

New research suggests common baker's yeast could withstand harsh conditions on Mars