Space agencies are planning to use origami to find a sustainable solution to space debris

A new study by Japanese researchers proposes a surprising solution to the growing problem of space debris: paper planes. Published in Acta Astronautica, the research explores using folded paper as a key component for sustainable spacecraft, which could burn up harmlessly upon re-entry, leaving no harmful waste behind. This unconventional approach aims to address the clutter of defunct satellites and rocket parts currently crowding low Earth orbit, per Phys.org.

The study's authors, Maximilien Berthet and Kojiro Suzuki from the University of Tokyo, used computer simulations and physical models to test their theory. Their simulations showed that a paper plane launched from the International Space Station could remain stable for four days before beginning to tumble as it re-entered Earth's atmosphere. The researchers predicted that the plane would ultimately burn up between 90 and 110 kilometers in altitude due to intense aerodynamic heating.

To validate their feelings, Berthet and Suzuki built a physical model of their plane and tested it in a hypersonic wind tunnel. The paper plane, which had an aluminum tail, was subjected to conditions mimicking atmospheric re-entry. Although the model experienced some bending and charring, it did not disintegrate, suggesting that a paper-based craft could endure the initial stages of re-entry before burning up completely. This research, which draws inspiration from the traditional Japanese art of origami, presents a novel way to combat space junk. The potential for paper-based spacecraft to be used for data collection and other missions without contributing to space debris offers a new path forward for more environmentally friendly space exploration.

While disposable paper airplanes may not seem like a useful tool for space exploration, the research team highlights this very quality as a significant advantage. The plane's sensitivity to atmospheric drag allows it to act as a passive probe for measuring air density. By analyzing the plane's orbital motions, scientists can reverse-engineer air density data. The low cost of these "paper space planes" means that multiple probes could be deployed simultaneously and at regular intervals, providing a new way to conduct distributed measurements of the low-Earth atmosphere, as mentioned on IFL Science.

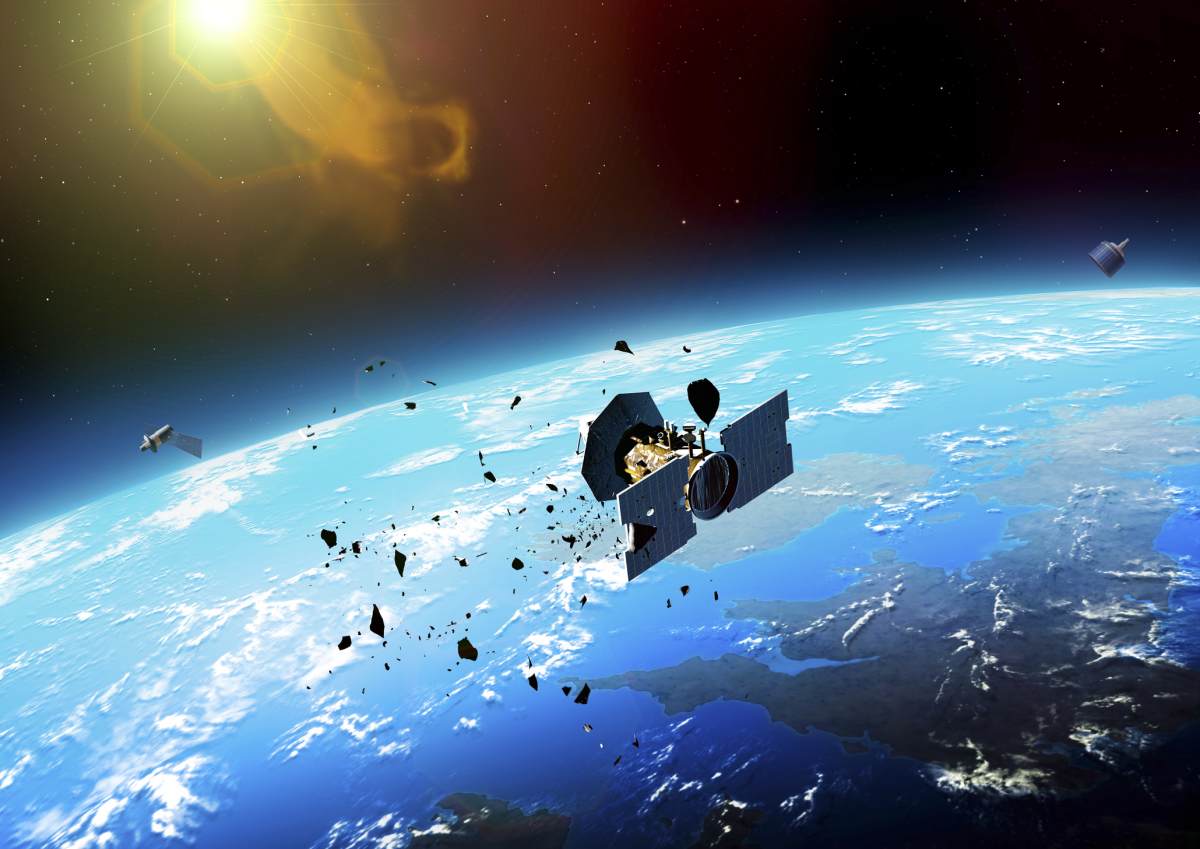

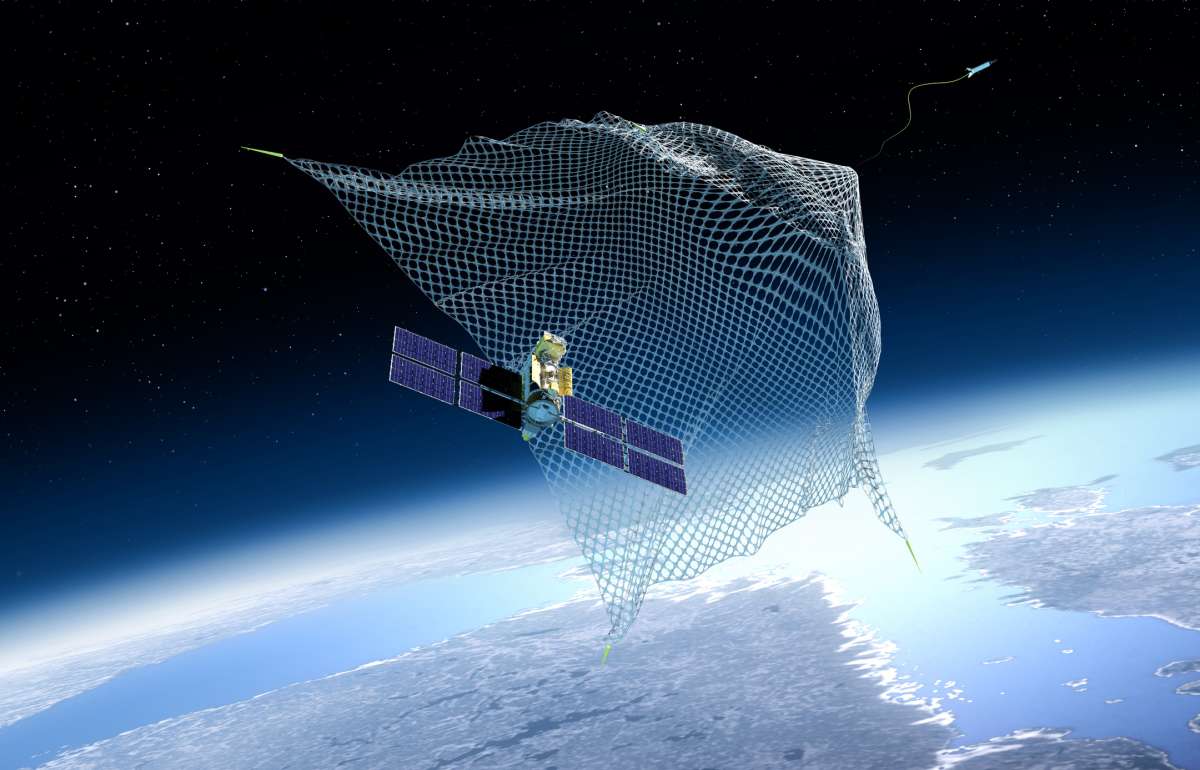

Beyond the Earth's atmosphere, a massive and dangerous junkyard has formed in low Earth orbit (LEO). This area is now filled with millions of pieces of human-generated space junk, or "orbital debris," including discarded rocket parts, defunct satellites, and tiny flecks of paint, according to NASA. Traveling at speeds up to 18,000 miles per hour, nearly seven times the speed of a bullet, the debris poses a significant risk to active satellites and future space missions. The problem has worsened dramatically in recent years. Two specific events, the 2007 destruction of the Chinese Fengyun-1C spacecraft and a 2009 collision between American and russian satellites, alone increased the amount of large orbital debris in LEO by an estimated 70%.

With an estimated 6,000 tons of material now orbiting the planet, LEO has become a cosmic garbage dump. The high cost of removal and the absence of international laws to govern cleanup efforts have made managing the issue a monumental challenge. While NASA's Orbital Debris Program, established in 1979, works to track and mitigate space junk, the responsibility ultimately falls on every country with spacefaring capabilities. The management of this debris is a shared challenge and a collective opportunity to preserve the space environment for generations to come.