Next solar superstorm could hit Earth harder than ever, scientists explain why

A groundbreaking study reveals that rising carbon dioxide levels in Earth’s atmosphere could dramatically alter the impact of solar superstorms, potentially increasing the risk to thousands of orbiting satellites. While the upper atmosphere is expected to become less dense overall, the relative shock from a storm could be far more severe, according to new research led by scientists at the US. National Science Foundation's National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR) and Japan’s Kyushu University, as per the National Science Foundation.

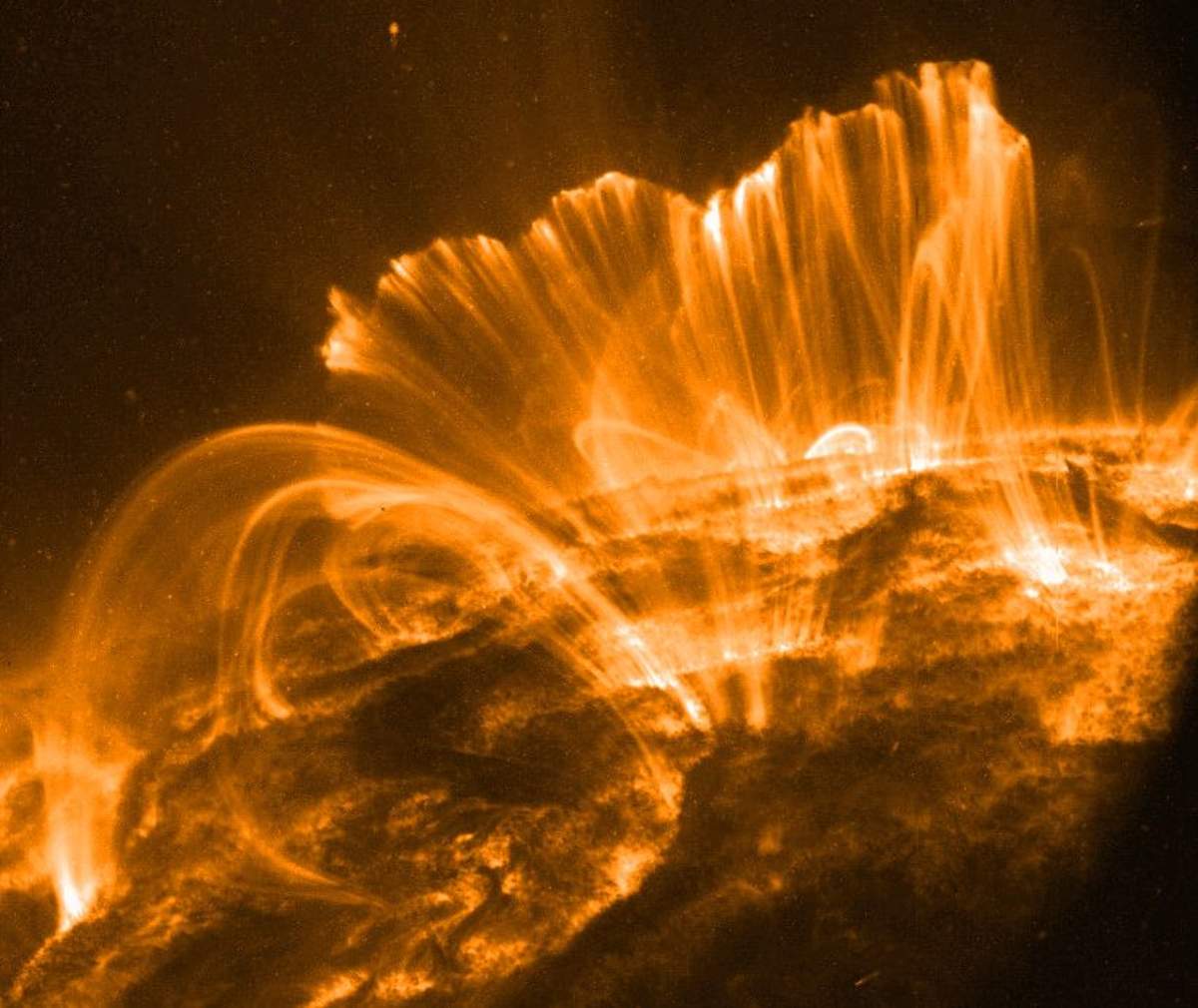

The findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, raise critical concerns for the satellite industry, which relies on predictable atmospheric conditions to operate effectively. Scientists have long known that massive eruptions of charged particles from the Sun can cause geomagnetic storms, which temporarily increase the density of the upper atmosphere. This increased drag can slow satellites, alter their orbits, and shorten their operational lifespans.

However, the new research shows a complex twist to this dynamic. As carbon dioxide concentrations increase, the upper atmosphere cools and thins. The study, which used a powerful computer model to simulate the effects of a superstorm, found that future storms will occur in an already less-dense environment. While the absolute increase in density will be lower than what we see today, the relative change will be significantly greater.

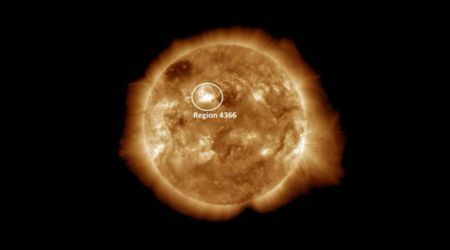

During a storm similar to the one that hit Earth in May 2024, the atmosphere’s density increases to more than twice its normal level. But in the future, with higher CO2 levels, the same storm could cause the density to nearly triple. “The way that energy from the Sun affects the atmosphere will change in the future because the background density of the atmosphere is different, and that creates a different response,” stated lead author Nicholas Pedatella, an NCAR scientist. “For the satellite industry, this is an especially important question because of the need to design satellites for specific atmospheric conditions.”

The study simulated the atmosphere's response to the May 2024 geomagnetic storm across four different years: 2016 and three future years (2040, 2061, and 2084). The results consistently showed a future with a thinner, yet more volatile, upper atmosphere.

Our increasing dependence on satellite-based technologies, from GPS navigation and internet access to national security systems, makes understanding these changes more urgent than ever. The study highlights the need for more research to fully grasp how future space weather will affect the planet. Scientists plan to study different types of geomagnetic storms and their impacts at various points in the Sun's 11-year cycle. “We now have the capability with our models to explore the very complex interconnections between the lower and upper atmosphere,” Pedatella explained. “It’s critical to know how these changes will occur because they have profound ramifications for our atmosphere.”

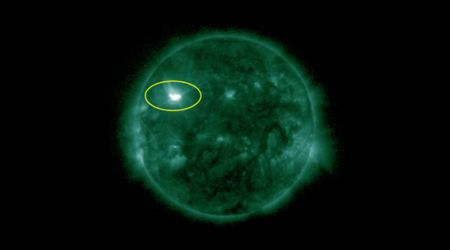

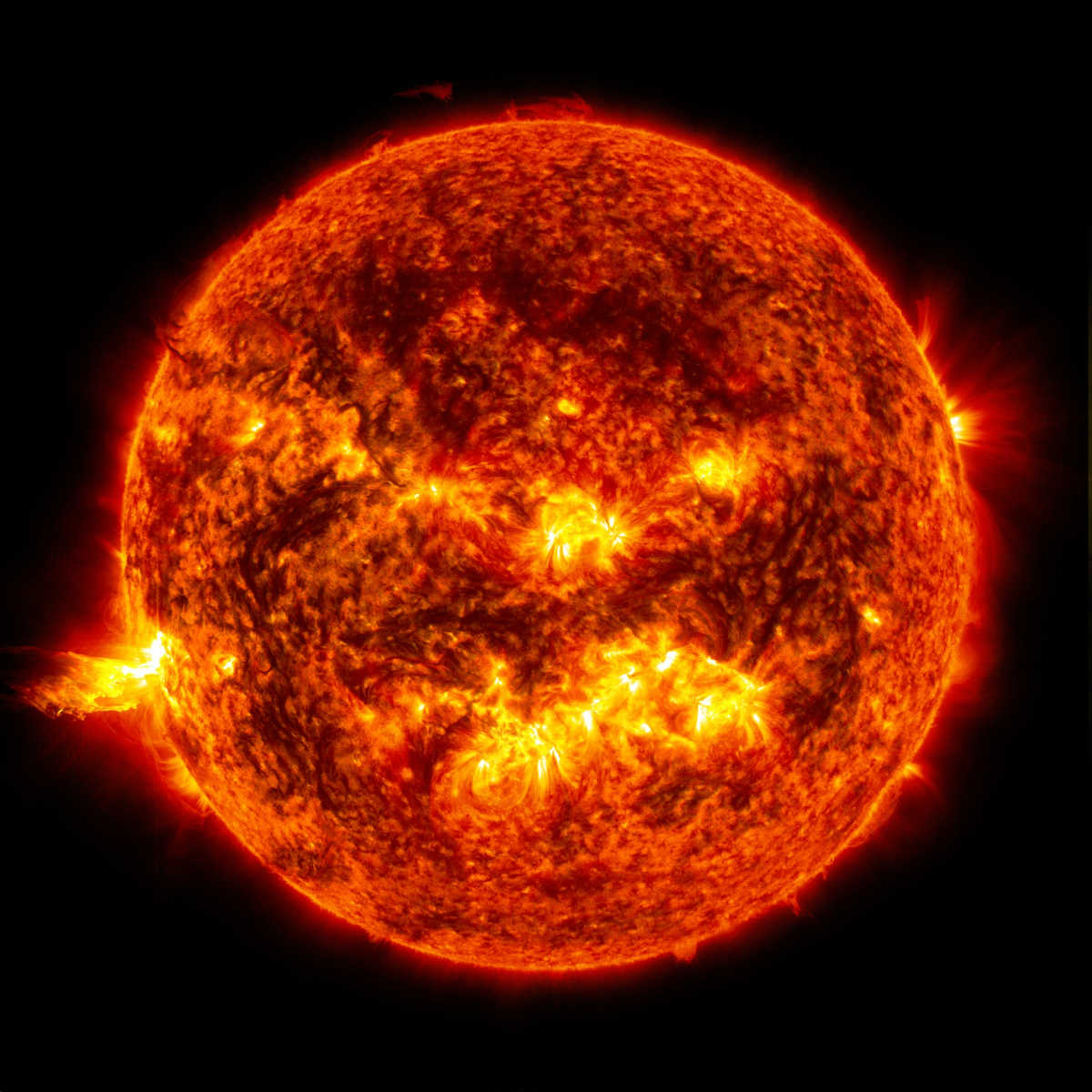

The destructive potential of solar storms, also known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), poses a significant threat to our increasingly satellite-dependent world. These powerful bursts of magnetism can cripple power grids, disrupt communication and navigation systems, and endanger astronauts in space. While scientists can observe these events as they happen, predicting their arrival on Earth has been a major challenge, as per NSF. A new initiative, the Coronal Solar Magnetism Observatory (COSMO), aims to change this. By providing unprecedented data on the Sun's magnetic field, COSMO could offer the crucial information needed to forecast when a solar storm will strike, giving Earth the time to prepare and protect its vital infrastructure.