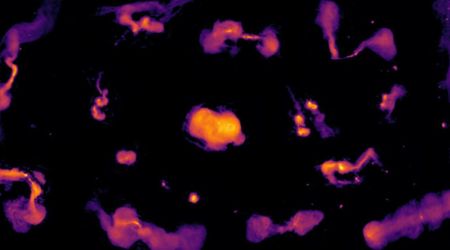

NASA’s Webb Telescope captures four coiled dust shells ‘spiraling’ Apep for the first time

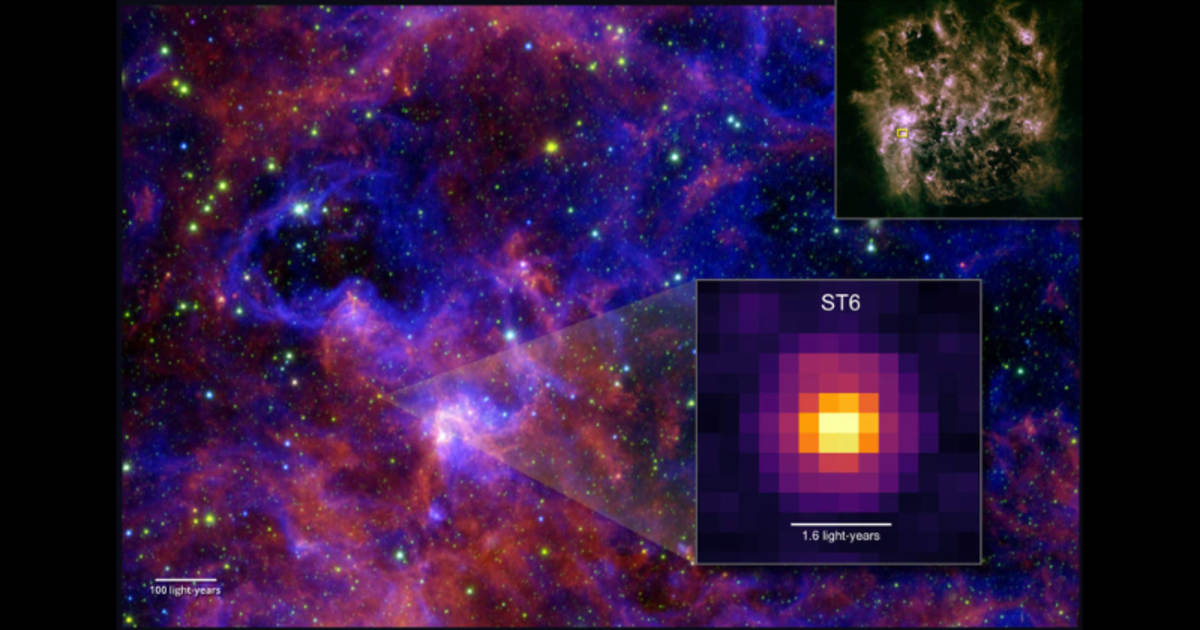

Some celestial worlds stay mysterious until the right eye finds the right thing. As per research published in The Astrophysical Journal, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has revealed a new detail of a pair of Wolf-Rayet stars known as Apep that astronomers had suspected for a long time but couldn’t confirm. Earlier, telescopes highlighted just a single dusty ring. Now, Webb has shown a crisp mid-infrared image of a system of four serpentine spirals of dust, one expanding beyond the next in the same pattern. The outermost ring is so faint that other instruments missed it entirely.

These shells were emitted over the last 700 years by the two aging Wolf-Rayet stars. This newfound clarity didn’t come from Webb alone. Years of data gathered by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope helped researchers narrow down the orbital rhythm of the pair. By combining Webb’s precise ring positions with VLT’s measurements of how fast each shell expands, astronomers landed on a surprising figure: the stars swing close to each other only once every 190 years. For roughly 25 of those years, during the tightest approach, their fierce winds collide, mix, and fling carbon dust into space, per NASA.

Wait, there is one more revelation! Webb confirmed that Apep is not just a duo but a trio. A supergiant star shares the system and orbits at a greater distance. Its presence isn’t obvious at first glance, because Webb shows all three as a single point of light. Its impact, however, is unmistakable. The supergiant slices through the dust, carving out a subtle V-shaped cavity that appears in each layer like the cut of a blade. Earlier observations had hinted at a third star, but Webb’s observations confirmed it.

For lead author and Caltech postdoctoral researcher Yinuo Han, learning this was like “switching on a light in a dark room.” Suddenly, the spirals, the gaps, the symmetry, and the chaos became visible. Co-author Ryan White noted how extraordinary Apep’s orbit is: while most dusty Wolf-Rayet binaries have orbits ranging between two and ten years, this one stretches well beyond a century. Moreover, the stars throw dense dust outward at high speeds between 1,200 and 2,000 miles per second. What Webb sees so clearly is made possible by the dust’s makeup: mostly amorphous carbon that retains a higher temperature long after leaving the stars behind. The grains are tiny, glow faintly, and are nearly impossible to detect from Earth’s surface, which is why only Webb’s MIRI instrument can pick them.

Apep’s future is already written in its stars. The two Wolf–Rayet giants began life far heavier than their supergiant companion, but have shed enormous amounts of mass. Each now sits at roughly 10 to 20 times the mass of our Sun, while the supergiant is closer to 40 or 50. Eventually, the Wolf-Rayet stars will explode as supernovae, quickly sending their contents into space. Either may also emit a gamma-ray burst, one of the most powerful events in the universe, before possibly becoming a black hole. Wolf-Rayet stars are rare enough that only about a thousand exist in our entire galaxy. Systems with two of them are rarer still, and Apep is the only known example of its kind in the Milky Way. With Webb now unfolding its history and structure, astronomers finally have the clearest look yet at one of the galaxy’s most unusual stellar families.

More on Starlust

Webb Telescope illuminates hidden black holes feasting on stars in dusty cosmic corners