NASA’s Parker Solar Probe caught the unexpected—the Sun's solar wind making a U-turn

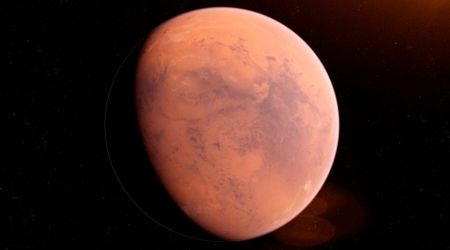

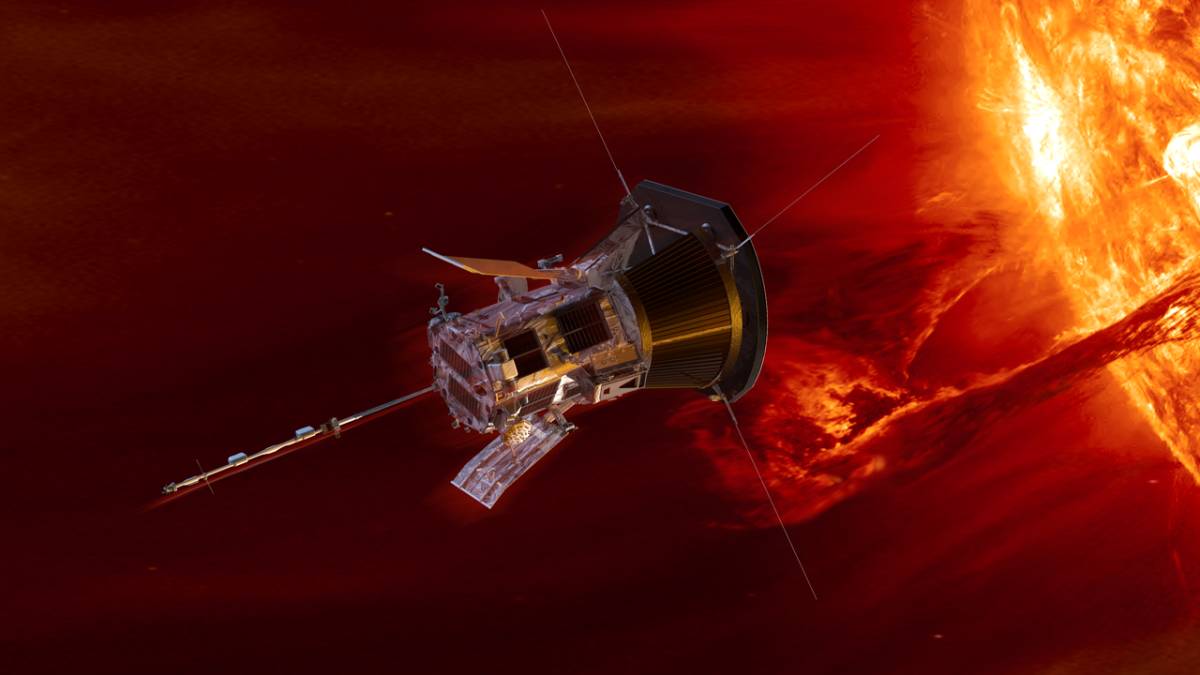

Surreal close-up images from NASA's Parker Solar Probe from 2024 have now revealed a never-before-seen process in which vast amounts of magnetic material, ejected from the Sun, fail to escape and instead, fall back toward the solar surface. The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, are based on data gathered during the spacecraft's record-setting closest approach to the Sun in December 2024, just 3.8 million miles from the star, according to NASA.

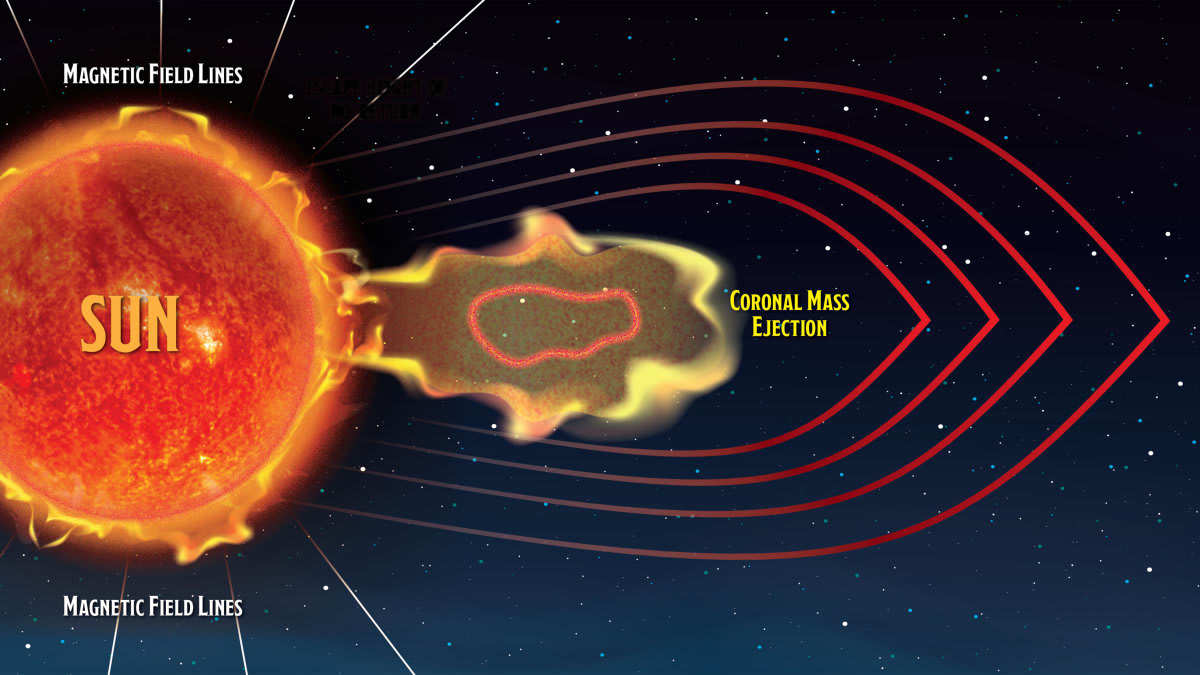

The Sun frequently ejects billions of tons of charged particles and magnetic fields in huge bursts called coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Major contributors to "space weather," these events have the potential to disrupt GPS satellites, cause power outages on Earth, and pose risks to astronauts and their electronic-based spacecraft. Predicting the direction and impact of these coronal mass ejections is essential in safeguarding infrastructure and future missions like Artemis.

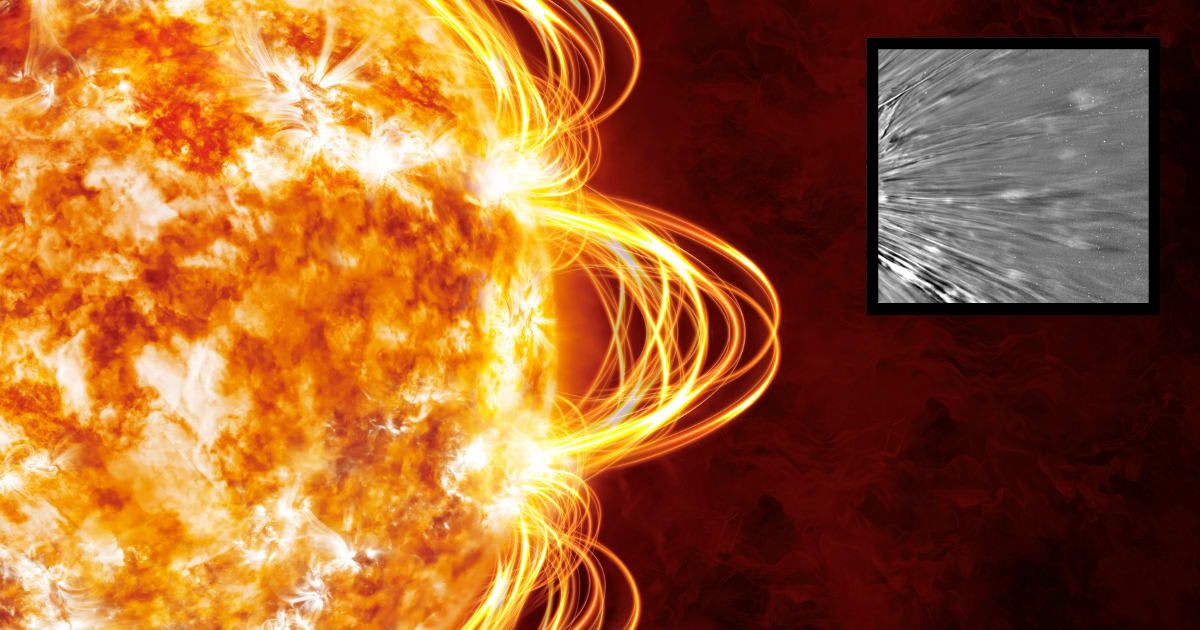

During the December 2024 event, a CME erupted, and in its wake, the probe's WISPR instrument clearly captured images of huge "blobs" of solar material streaming back toward the Sun. Though previous and distant missions had hinted at this phenomenon, known as "inflows," the probe's unprecedentedly close view let scientists measure the speed and size of the falling material for the first time ever. “These breathtaking images are some of the closest ever taken to the Sun and they’re expanding what we know about our closest star,” said Joe Westlake, the director of the heliophysics division at NASA.

Previously, scientists believed that during a CME, all the magnetic field lines fully break free from the Sun, but now they believe some lines tear and immediately reconnect to form loops that fall back and drag solar material with them. The process acts like a giant "recycling" system for the Sun's magnetic fields. Crucially, the falling-back material reshapes the Sun's atmosphere and changes the magnetic landscape underneath. Scientists say that this newfound process might cause subtle yet important shifts in the path of subsequent CMEs.

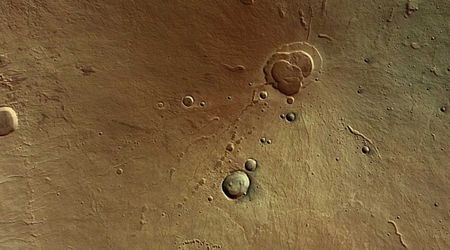

“That’s enough to be the difference between a CME crashing into Mars versus sweeping by the planet with no or little effects,” explained Angelos Vourlidas, a researcher with the WISPR team. The new data is already being incorporated to improve models for predicting space weather across the solar system, giving scientists a better long-term picture of how the Sun's activity could impact our technological world and future deep-space exploration.

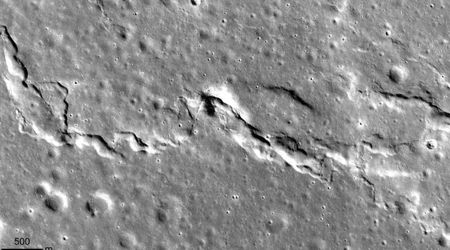

In a parallel breakthrough, Parker Solar Probe has also provided the first-ever direct confirmation of a decades-old theory describing magnetic reconnection. It is an important process whereby magnetic field lines break violently and snap back together, releasing enormous energy. This process is one of the key drivers behind space weather events such as solar flares and CMEs.

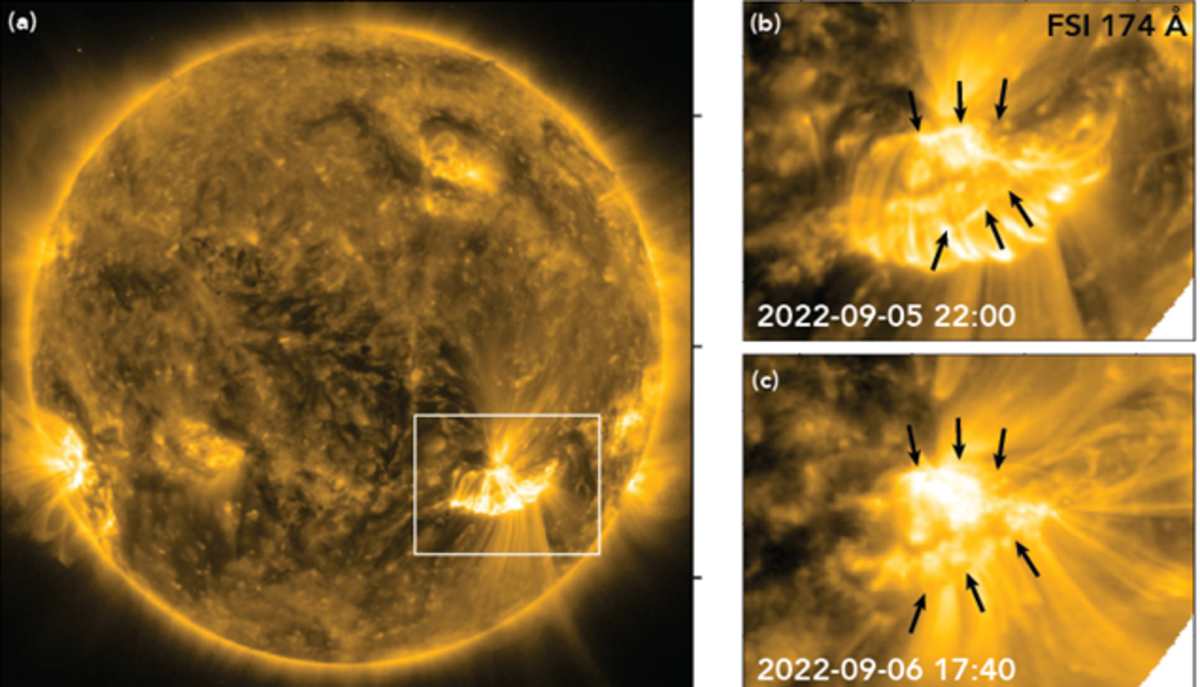

This groundbreaking validation came from the only spacecraft ever to fly directly into the Sun's upper atmosphere. In this new study, led by the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the researchers used observations from PSP's September 2022 flyby. During that event, the probe plunged straight through a massive solar eruption, offering a unique opportunity to measure the plasma and magnetic field properties within the reconnection zone itself.