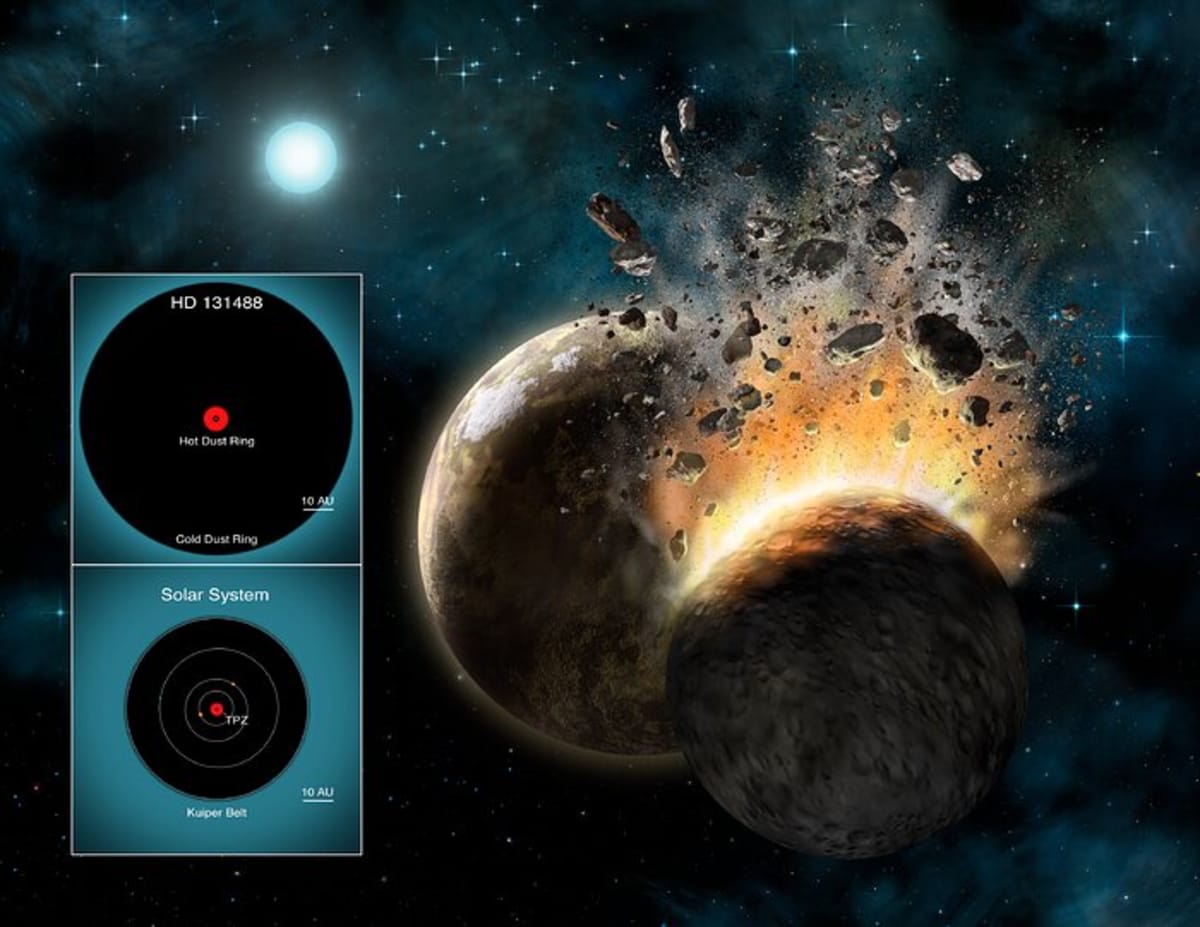

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope captures rare sight of comet smoke around a nearby star

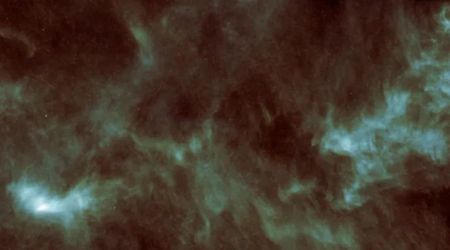

Astronomers have used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to uncover the luminous remnants of comets that have been vaporized by the heat of a young, neighboring star, thereby providing a unique opportunity to observe how planet formation occurs. The finding, which is presently accessible on the preprint server arXiv, indicates that the stellar system's gas is the continual result of a huge, unceasing brawl among exocomets.

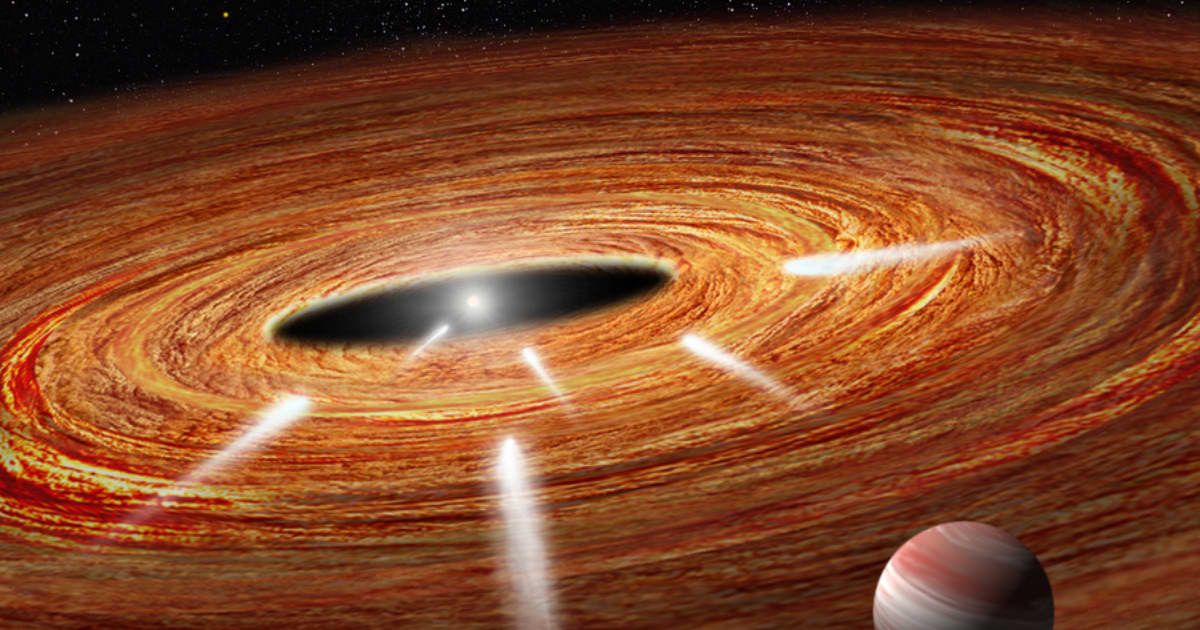

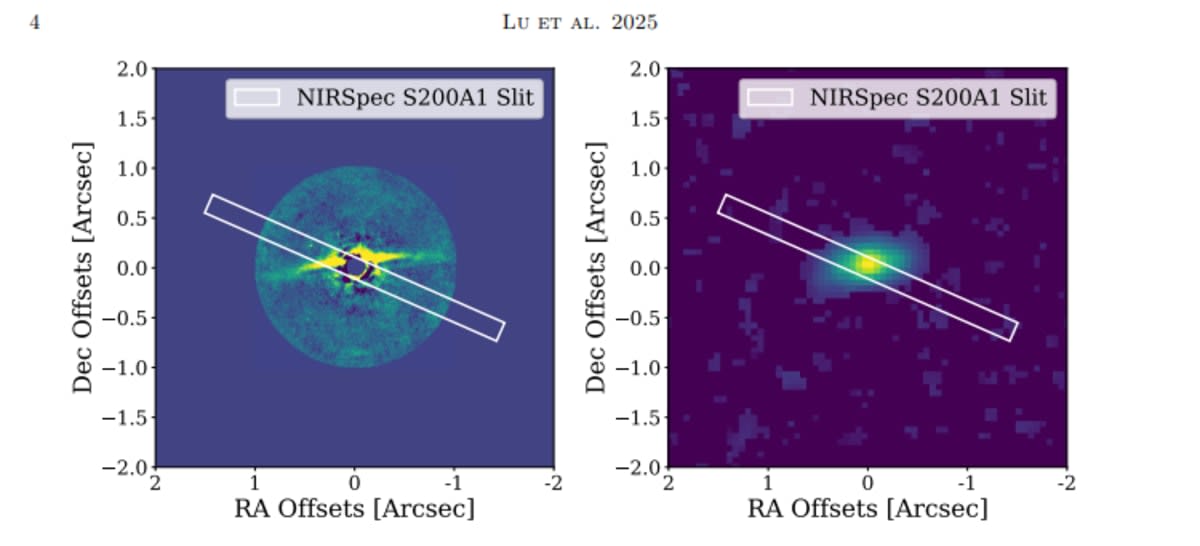

An investigation done by science fellow Cicero Lu of the Gemini Observatory has shown that a star named HD 131488, which is placed at a distance of 500 light-years from Earth, is encircled by a cloud of carbon monoxide gas that is "warm". On the one hand, radio telescopes had previously detected cold gas in the outskirts of the celestial system; on the other, JWST’s infrared sensors could allow scientists to look more closely into the "terrestrial zone," the interior area where Earth-like planets are mostly formed, per Universe Today.

The telescope has, this time, brought to light a distinct process: UV fluorescence. The molecules of carbon monoxide in the inner disc are so much subjected to the star's radiation that their internal vibrations reach even a phenomenal 8,800K, while the gas itself is not that hot in reality. This glowing effect resembles a chemical fingerprint, and thus, it permits the researchers to trace the origin of the gas.

The research results finish off a debate that lasted quite some time about "CO-rich" debris discs. For years, scientists were in doubt whether the gas was a remnant fossil from the star's birth or if it was being produced by the star's nature. The evidence from HD 131488 strongly supports a second generation of gas. The detection of water vapor points to the possibility that icy comets are either colliding with each other or are being heated by the star, thus releasing gas in the process. Alongside, the lack of hydrogen in the interior disc shows that this material is not from the time of the star's formation, but it is smoke from recent planetary dust.

This finding greatly affects the kinds of planets that might be forming around HD 131488. In such an environment and being rich in carbon and oxygen while poor in hydrogen, the planets that would be emerging would most probably be metal-rich rather than gas giants like Jupiter. HD 131488, being merely 15 million years old, is still very young. By the study of the "exocometary" activity in the vicinity, the scientists are in fact monitoring the disorderly yet vital process of a solar system bringing in its inner neighborhood the chemical building blocks of life.

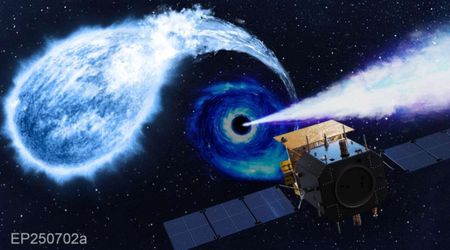

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is not only mapping the chemistry of the stars that are nearby but also resolving some of the mysteries that belong at the very edge of the observable universe. Separately, astronomers have successfully elucidated one of the 20-year-old puzzles: how did supermassive black holes grow to such huge sizes so fast after the Big Bang? The thing is, ordinary stars are just not massive enough to collapse into billion-ton black holes within such a short period of cosmic time. Yet, according to JWST's new findings, a shorter route could have been utilized.

More on Starlust

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope finds a lemon-shaped exoplanet with a never-before-seen atmosphere

Scorching 'lava world' detected by James Webb Telescope surprises scientists with a thick atmosphere