Largest ever black hole merger, 225 times the mass of the Sun, detected by LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA

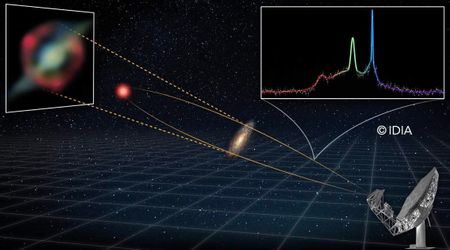

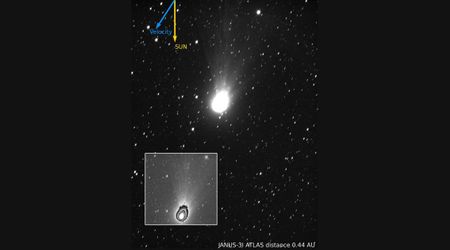

Scientists operating the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO), Virgo, and KAGRA collaboration (LVK) have announced the detection of the most massive black hole merger ever observed via gravitational waves. The event recorded on November 23, 2023, produced a colossal new black hole with a mass approximately 225 times that of our Sun, as mentioned on Phys.org.

Designated GW231123, this extraordinary event eclipses previous records and challenges existing theories about black hole formation. The signal was captured during the LVK network's fourth observing run. The LVK Collaboration has revolutionized astronomy since the first direct detection of gravitational waves in 2015. While that initial observation involved a black hole merger resulting in a final mass 62 times that of the Sun, the latest significantly raises the bar.

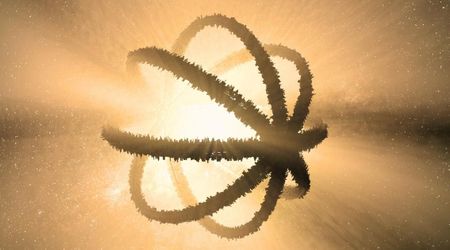

LIGO, with twin detectors in Louisiana and Washington, joined forces with the Virgo detector in Italy and KAGRA in Japan to form the LVK network. Together, these observatories have now recorded hundreds of black hole mergers. The prior record-holder, GW231123, detected in 2021, involved a merger totaling 140 solar masses. GW231123's final mass is nearly twice that amount, resulting from the coalescence of two rapidly spinning black holes, each approximately 100 and 140 solar masses. The extreme size and rapid rotation of the black holes in GW231123 are pushing the limits of current theoretical understanding. "This is the most massive black hole binary we've observed through gravitational waves," stated Mark Hannam of Cardiff University and an LVK collaborator. "It presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation."

Standard stellar evolution models struggle to account for black holes of this immense size, leading researchers to suggest that these giants may have formed through sequential mergers of smaller black holes. Dave Reitze, executive director of LIGO at Caltech, emphasized that this discovery highlights the unique role of gravitational waves in revealing the "fundamental and exotic nature of black holes throughout the universe."

Analyzing the intricate signal of GW231123 demanded sophisticated modeling techniques capable of interpreting the dynamics of rapidly spinning black holes. Charlie Hoy of the University of Portsmouth noted that the black holes in the event appear to be spinning near the maximum speed allowed by Einstein's theory of general relativity, making the signal particularly complex to interpret. Researchers are using this data to advance their theoretical tools.

"It will take years for the community to fully unravel this intricate signal pattern and all its implications," said Gregorio Carullo of the University of Birmingham. The LVK Collaboration continues to process data from the fourth observing run, which began in May 2023. This landmark detection underscores the potential of gravitational-wave astronomy. "This event pushes our instrumentation and data-analysis capabilities to the edge of what's currently possible," said Sophie Bini, a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech. GW231123 data will be presented this week at the GR-Amaldi meeting in Glasgow, Scotland, and made available for global analysis through the Gravitational Wave Open Science Center.

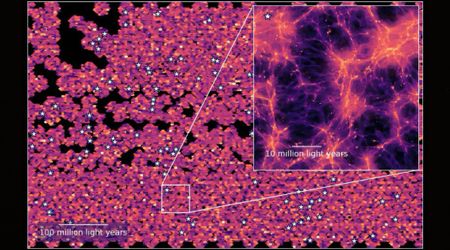

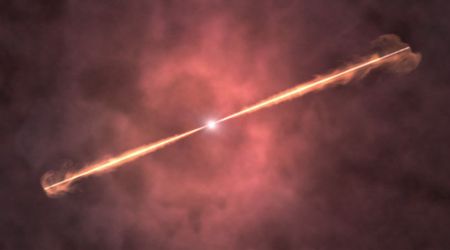

Gravitational waves are disturbances in the very structure of space-time, traveling at the speed of light. These ripples serve as indicators of the universe's most catastrophic echoes from the Big Bang. As these waves pass, they momentarily distort matter along their path, stretching and compressing objects due to the force of gravity, as per NASA.