Jupiter's unique dilute core probably formed gradually rather than from a planetary collision, study claims

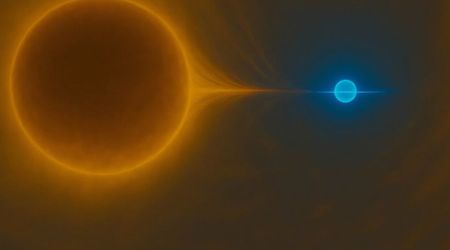

A new study is turning a long-held theory about the formation of Jupiter's core on its head, suggesting that a colossal collision may not have been responsible for its unique structure. For some time, scientists believed that a violent impact with an early planet, one containing roughly half of Jupiter's core material, could have been the event that mixed the gas giant's central region, as per the Royal Astronomical Society.

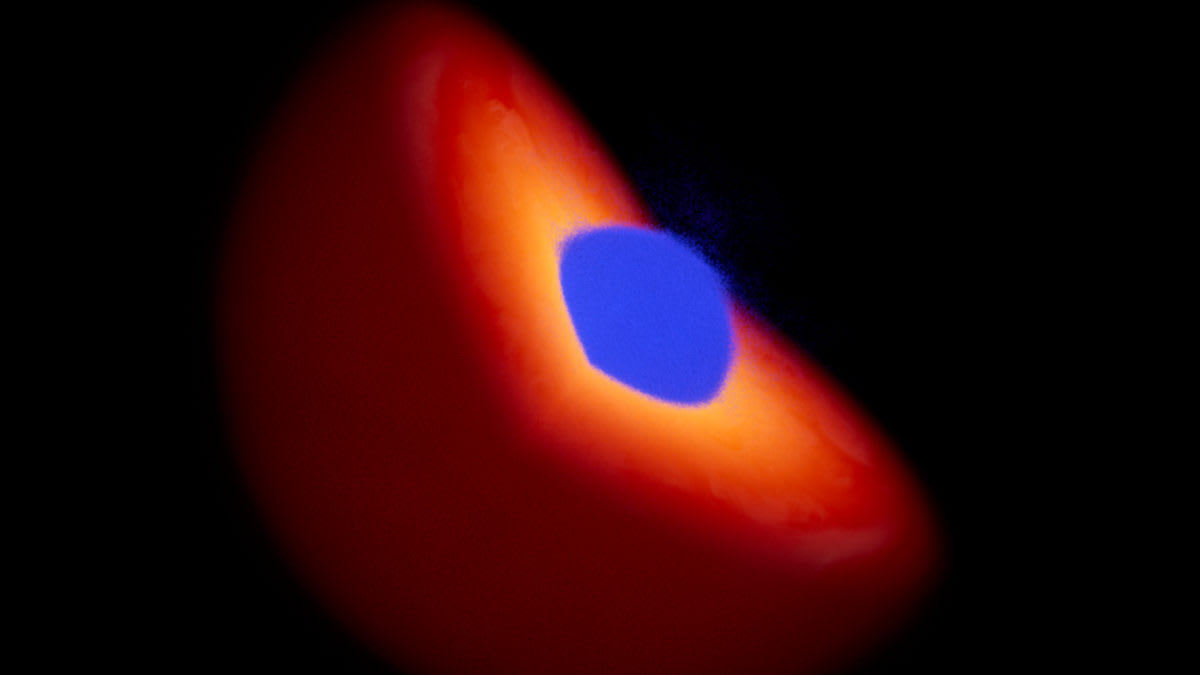

This mixing, it was thought, explained the core's modern-day interior. However, new research published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society suggests that Jupiter's unique makeup is actually the result of how the growing planet absorbed heavy and light materials as it formed and evolved. Unlike what scientists once expected, the core of our solar system's largest planet doesn't have a sharp boundary but rather gradually blends into the surrounding layers of hydrogen, a structure known as a dilute core. The formation of this dilute core has been a key question for scientists ever since NASA's Juno spacecraft first revealed its existence.

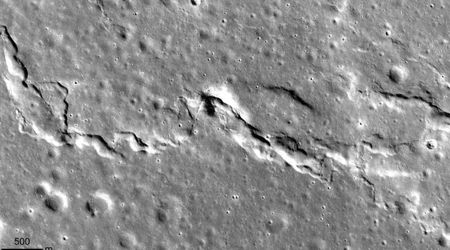

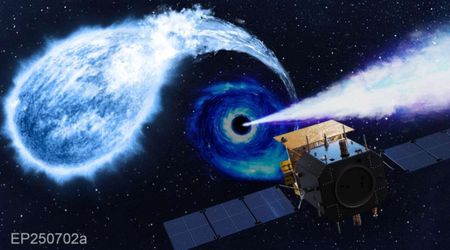

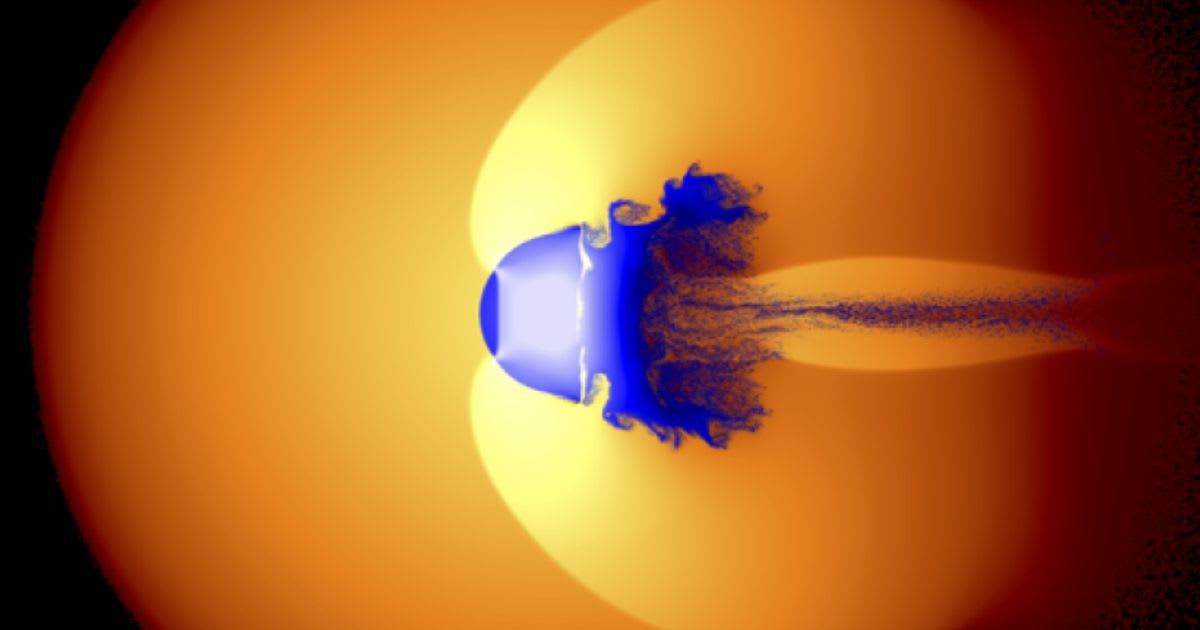

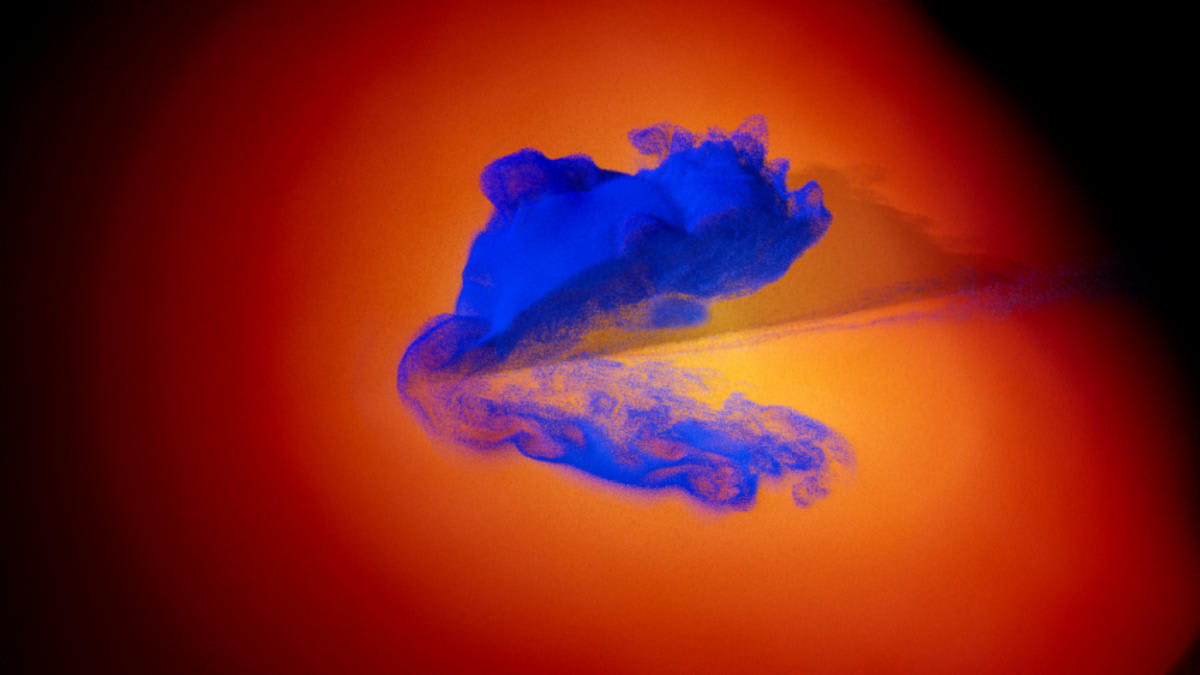

Using advanced supercomputer simulations of planetary impacts, a team of researchers from Durham University, in collaboration with scientists from NASA, SETI, and CENSSS, tested whether a massive collision could have created Jupiter's dilute core. The simulations, which were run on the DiRAC COSMA supercomputer at Durham University, did not produce a stable dilute core structure.

Instead, the simulations demonstrated that the dense rock and ice material displaced by an impact would quickly re-settle, leaving a distinct boundary with the outer layers of hydrogen and helium. This finding contradicts the idea of a smooth transition zone between the two regions. Sharing his perspective on the study, lead author Dr. Thomas Sandnes, of Durham University, said: "It's fascinating to explore how a giant planet like Jupiter would respond to one of the most violent events a growing planet can experience. We see in our simulations that this kind of impact literally shakes the planet to its core – just not in the right way to explain the interior of Jupiter that we see today."

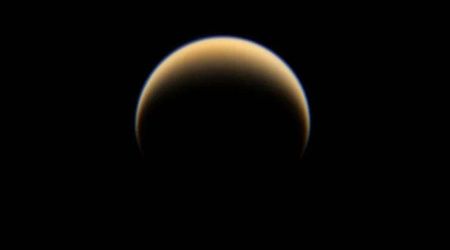

This phenomenon isn't exclusive to Jupiter; recent evidence suggests that Saturn also has a dilute core. Dr. Luis Teodoro, of the University of Oslo, weighed in, stating: "The fact that Saturn also has a dilute core strengthens the idea that these structures are not the result of rare, extremely high-energy impacts but instead form gradually during the long process of planetary growth and evolution." The findings could help scientists better understand the many Jupiter and Saturn-sized exoplanets observed around distant stars. If dilute cores are not the product of rare, extreme impacts, then perhaps most or all of these planets have comparably complex interiors, as mentioned by the outlet.

Dr. Jacob Kegerreis, a co-author of the study, summarized the findings, saying: "Giant impacts are a key part of many planets' histories, but they can't explain everything!" He added that the project has also accelerated the development of new ways to simulate these cataclysmic events in greater detail, which will help scientists continue to narrow down how the amazing diversity of worlds in our solar system and beyond came to be.