Astronomers spot possible 'first-of-its-kind superkilonova' from two separate stellar explosions

Astronomers are reporting a highly complex and potentially groundbreaking cosmic event that may be the first-ever observed "superkilonova," an ultra-powerful explosion produced by two closely timed stellar blasts. According to Caltech, the event, labeled AT2025ulz, initially behaved like a standard kilonova, only to later evolve into something that appeared more like a common supernova, leaving scientists confused.

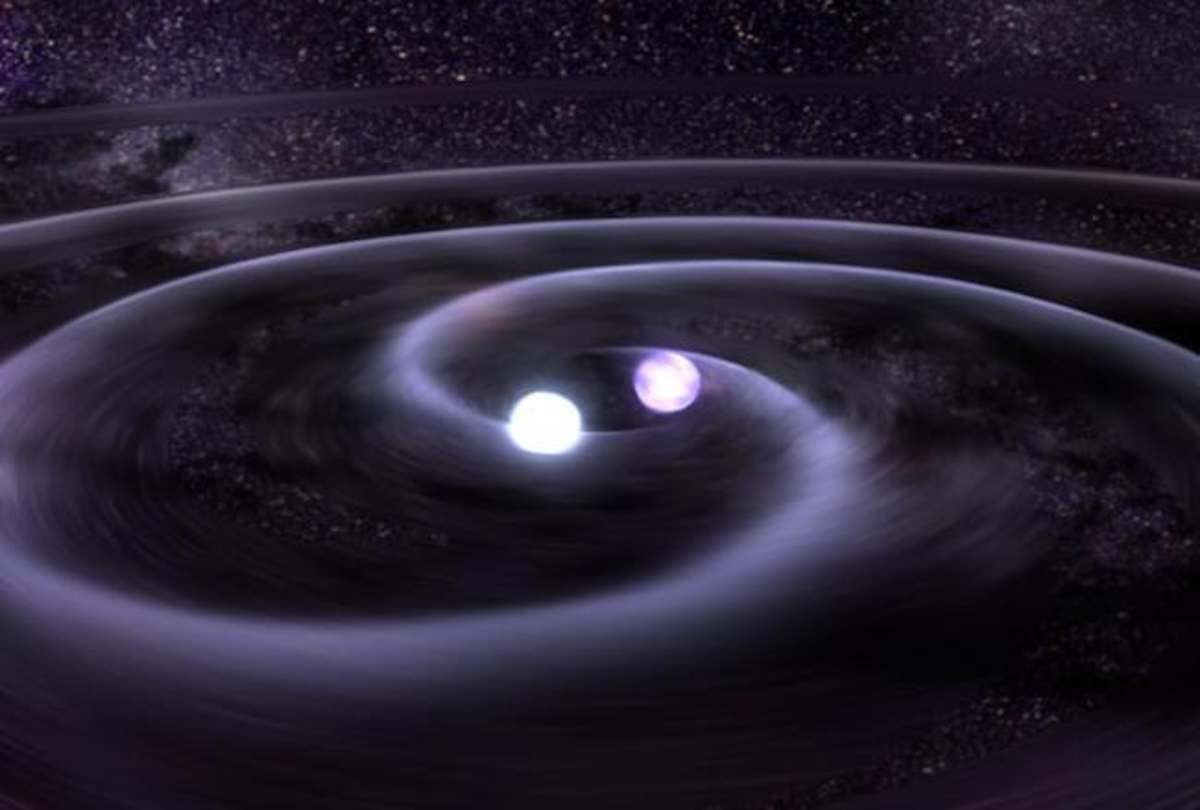

The findings, outlined in a letter submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggest that a kilonova, an explosion produced when two dead, dense stars called neutron stars crash together and forge heavy elements like gold, may have been preceded and partially concealed by a supernova blast occurring just hours earlier. "While not as highly confident as some of our alerts, this quickly got our attention as a potentially very intriguing event candidate," said David Reitze, the executive director of LIGO and a research professor at Caltech. "We are continuing to analyze the data, and it's clear that at least one of the colliding objects is less massive than a typical neutron star."

Astronomers are reporting evidence for a possible second kilonova event, but the case is not closed. In fact, this situation is much more complex.https://t.co/K8t8GkSRM3 pic.twitter.com/UkN6Wt3h7R

— Caltech (@Caltech) December 16, 2025

The sequence started on August 18, 2025, with the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors picked up a disturbance in spacetime, consistent with the merger of two objects, one much smaller than the other, possibly a neutron star with a mass below that of our Sun.

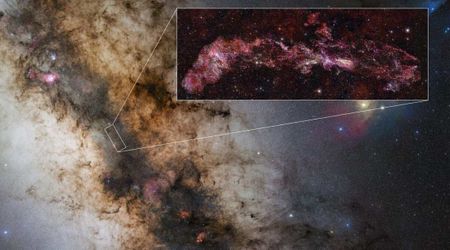

Just minutes later, the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at Caltech's Palomar Observatory detected a rapidly fading red glow from the same location, 1.3 billion light-years away. Over the first few days, the light signature was consistent with the only confirmed kilonova, GW170817, detected in 2017, which generated heavy elements that glowed red. But after a week, the event took a surprising turn: It brightened, shifted to blue, and produced hints of hydrogen, all the hallmarks of a classic supernova. Those developments convinced most astronomers that the light had nothing to do with the gravitational wave signal; it was just a common supernova.

Astrophysicist Mansi Kasliwal of Caltech, the study's lead author, and her team remained curious. They noted that the gravitational-wave data indicated the merger of two small, or "sub-solar," neutron stars, objects that theorists have suggested are born only during a specific, rapid kind of supernova explosion. The team now theorizes that the initial supernova blast created two of these small neutron stars. These newly formed stars then almost immediately collided to create the powerful kilonova explosion and the resulting gravitational waves. The expanding debris from the initial supernova then obscured the kilonova, making the entire event look like a later, standard supernova. "A supernova may have birthed twin baby neutron stars that then merged to make a kilonova," explained co-author Brian Metzger of Columbia University.

The team stresses, however, that while the theory of a supernova-spurred kilonova, or "superkilonova," is attractive, hard confirmation is currently impossible. In fact, it is a warning that future kilonovae might not resemble the 2017 event and hence, could be misclassified as supernovae. Astronomers will continue to search for more examples in data from upcoming instruments, including the Vera Rubin Observatory and NASA’s Nancy Roman Space Telescope, to confirm the existence of this predicted, dual-explosion phenomenon.

More on Starlust

NASA’s Roman Space Telescope survey aims to discover 100,000 star explosions and feeding black holes