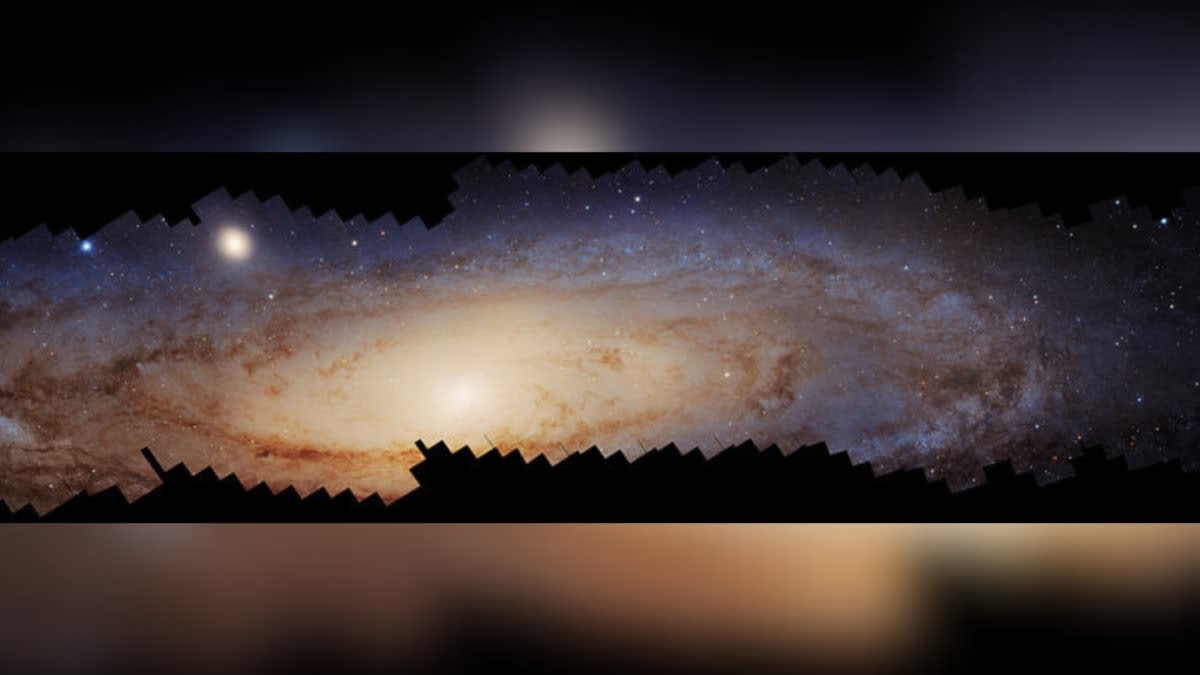

Andromeda is headed toward the Milky Way, while other galaxies are moving away—and now we know why

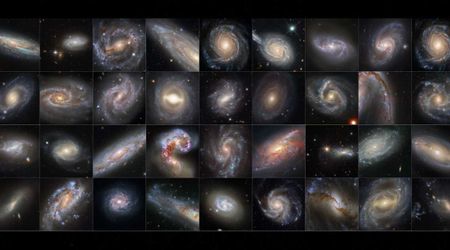

Why is the Andromeda Galaxy moving toward us while other neighboring galaxies are speeding away? For decades, such galactic movements have puzzled astronomers. Now, computer simulations by Ewoud Wempe, a PhD graduate student at the Kapteyn Institute of the University of Groningen (UG) in the Netherlands, and his collaborators from Germany, France, and Sweden, show that the dark matter lying beyond the Local Group that includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy is arranged in a flat structure measuring tens of millions of light-years. Above and below this sheet are huge empty spaces. The gravitational pull of the dark matter overwhelms the attraction between our galaxy and the neighboring galaxies, the researchers have reported in a paper published in Nature Astronomy.

It was in the 1920s when astronomer Edwin Hubble first figured out that the universe is expanding and galaxies are receding from each other. In fact, his eponymous law claims that galaxies are moving away from us at speeds that are proportional to their distances. But even in Hubble’s time, it was clear that Andromeda did not abide by this rule. It is currently heading towards us at a speed of 100 kilometers per second.

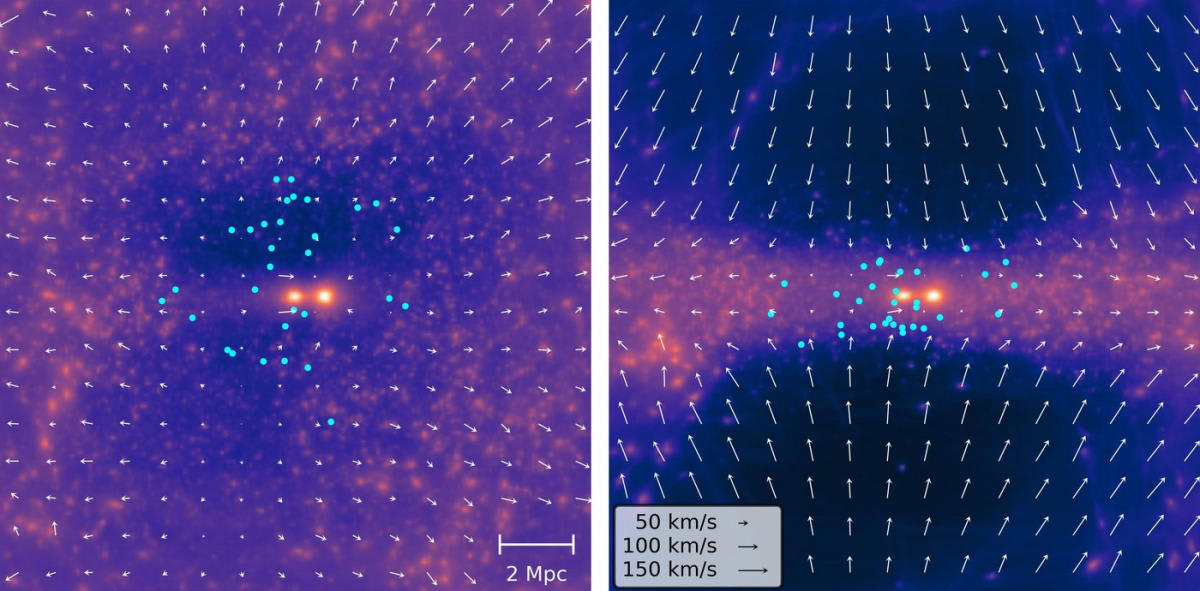

In 1959, astronomers Franz Kahn and Lodewijk Woltjer found evidence of dark matter situated around Andromeda and the Milky Way. They came to the conclusion that for the gravity of the two galaxies to have reversed the initial expansion, their combined mass must be more than 1000 billion times the mass of our Sun. That is way more than the mass of all their stars put together. This missing mass is accounted for by the dark matter halos around each galaxy that have set the two on a possible collision course. However, to get to the bottom of why other galaxies are moving away, the team, led by Wempe, simulated the early universe and its gradual evolution and then went on to reproduce the masses, positions, and velocities of the Milky Way and Andromeda, as well as those of the 31 galaxies lying just outside the Local Group.

"In the computer result with the flat mass distribution, the 31 surrounding galaxies have a velocity comparable to that observed. Galaxies are moving away from us, despite the mass of the Local Group. The explanation is that for nearby galaxies in the plane, the gravitational pull of the Local Group is counteracted by the mass further away in the plane. And outside the plane, where you would expect matter to be moving towards us, there are no galaxies,” a statement from the University of Groningen explained. Simon White, study co-author and director emeritus of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, told LiveScience that the external galaxies would have been receding at a slower pace if the mass around the Local Group were distributed spherically. "Instead, the flattened distribution of the surrounding matter pulls these galaxies outwards in a way which almost exactly compensates for the inward pull of the [Milky Way] and [Andromeda]," he added.

Overall, when accounting for the vast sheet of mass, the accurate modelling of the simulations reconciles experimental results with astronomical observations of galactic motions, as well as with the leading model of cosmology, known as Lambda Cold Dark Matter. "We are exploring all possible local configurations of the early universe that ultimately could lead to the Local Group," Wempe said in the University of Groningen statement. "It is great that we now have a model that is consistent with the current cosmological model on the one hand, and with the dynamics of our local environment on the other."

More on Starlust

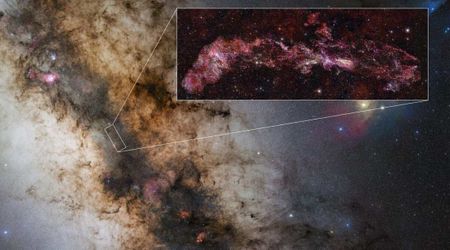

Astronomers build largest molecular cloud catalog of the Andromeda galaxy

Not every galaxy has a supermassive black hole like the Milky Way's, NASA's Chandra Telescope finds