What triggers massive Milky Way stars to run away from their birthplaces?

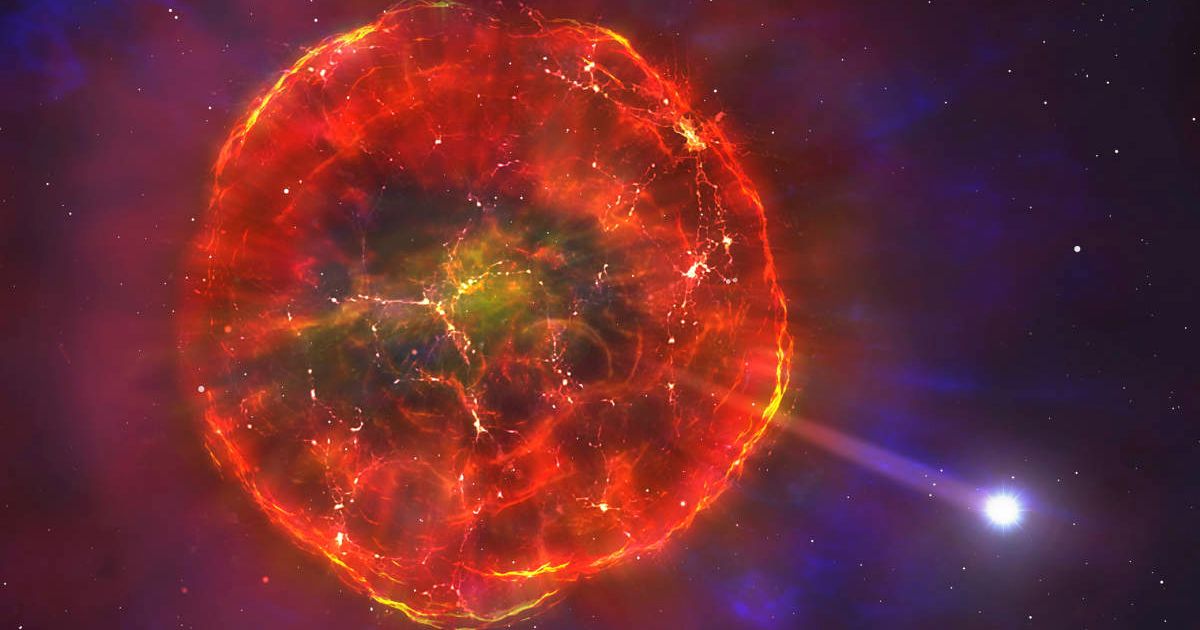

The Milky Way has a specific class of massive stars that drift away from their birthplaces at high speeds. Astronomers have long attributed the "fugitive" nature of these stars to two possible scenarios—a powerful push from the supernova explosion of a companion star in a binary system or close encounters in dense and young star clusters that resulted in a gravitational ejection. A new study, led by researchers from the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC) at the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona (ICCUB), helps provide a better understanding of these scenarios.

For the study, the research team scanned the sky with Gaia, the European Space Agency’s "billion star surveyor." They homed in on 214 of the most massive and bright stars in the Milky Way, which are known as O-type stars. Armed with high-quality spectroscopic information from the IACOB project, they measured these stars’ rotation speed and determined whether they are single or part of a binary system. “This is the most comprehensive observational study of its kind in the Milky Way,” said researcher Mar Carretero-Castrillo, a member of the ICCUB and the lead author of the study, in an IEEC press release. “By combining information on rotation and binarity, we provide the community with unprecedented constraints on how these runaway stars are formed.”

The results were astonishing. The researchers found that most runaway stars rotate slowly. Those that rotate fast might have links to supernova explosions in binary arrangements. As for the stars that move fast, they are likely single, indicating that they might have been ejected because of gravity. Additionally, the research team found that there are virtually no massive stars that are both very fast rotators and very fast movers. Among the gigantic stars, 12 are runaway binary systems that include three known high-mass X-ray binaries that contain neutron stars or black holes. Besides, three other binary systems were found to be promising candidates to host black holes. Understanding the mechanisms of massive runaway stars is extremely crucial for refining existing models of stellar evolution, supernovae, and the formation of gravitational wave sources. That's because these stars travel through the interstellar medium, sprinkling seeds that might one day grow into planets and other stars.

The researchers expect future data releases from Gaia and ongoing spectroscopic surveys to help them expand the sample size of these runaway stars, figure out their past trajectories, and ultimately trace them back to their birthplaces. It may also help in the detection of more exotic systems such as high-energy binaries that harbor neutron stars or black holes.

More on Starlust

NASA's JWST discovers massive Milky Way-like spiral galaxy just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang

Astronomers using JWST discover an ancient supernova from the first billion years of the universe