Ursa Major III may be a dense star cluster hiding a black hole core, claim astrophysicists

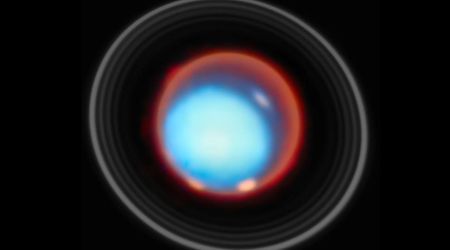

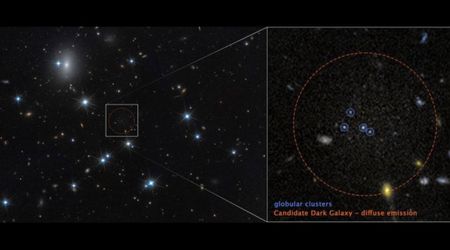

An international team of astrophysicists is challenging the long-held belief that Ursa Major III, one of the faintest objects in our galaxy, is a dwarf galaxy dominated by dark matter. New research suggests this celestial body, which orbits the Milky Way, may be a dense star cluster with a black hole at its core, as per the University of Bonn.

The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, propose a different origin for this cosmic anomaly. Ursa Major III has long puzzled scientists due to its surprisingly high mass-to-light ratio, a characteristic that led to the theory that it was a dwarf galaxy comprised primarily of dark matter.

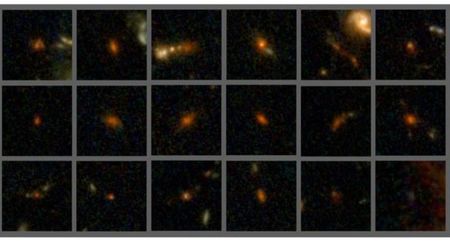

"Neither established dark matter models nor alternative theories have been able to satisfactorily explain the exact causes. Such intermediate objects are therefore considered a 'hot topic' in astrophysics and are the subject of intensive research,” said Dr. Ali Rostami-Shirazi, a doctoral student at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences in Iran. The research team's new simulations suggest that Ursa Major III's immense mass isn't due to dark matter, but rather to a core of compact objects like black holes and neutron stars.

According to co-author Professor Hosein Haghi of the University of Bonn, this 'dark star cluster' likely formed over billions of years as gravitational interactions with the Milky Way stripped away its outer stars. What remains is a dense, massive core that emits little to no light. The study argues that this effect has been misinterpreted as evidence of dark matter. To test their hypothesis, the researchers used N-body simulations to reconstruct the evolution of Ursa Major III. These calculations, based on the latest observational data, show that a dense core of black holes and neutron stars can explain the object's current structure without the need for dark matter.

"Our work shows for the first time that these objects are most likely normal star clusters," said Professor Pavel Kroupa of the University of Bonn. He added that these results solve a major mystery in astrophysics and show how advanced computer simulations can eliminate the need for "exotic components." The Bonn team, which has developed specialized numerical methods for these complex systems, believes this work provides a new foundation for understanding mysterious celestial objects and opens up new perspectives in galaxy research, as mentioned on the University of Bonn's official site.

Ursa Major, the same constellation that hosts Ursa Major III, is also home to a striking pair of galaxies, M81 and M82. These galaxies are a rewarding target for amateur astronomers, though they can be tricky to locate.

M81, a stunning spiral galaxy, is bright enough to be seen with binoculars, but it's positioned far from any easy-to-find reference stars. To pinpoint its location, first find the stars Phecda and Dubhe in the Big Dipper. Extend a line from Phecda, through Dubhe, and continue for the same distance; this path will bring you within a degree of M81. The galaxy is also near the star 24 Ursae Majoris, which forms a small triangle pointing toward M81.