Scientists stunned as star survived and returned for second near-fatal encounter with supermassive black hole

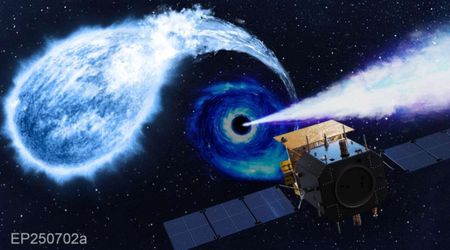

In a groundbreaking discovery, astronomers have observed a star that not only survived a close encounter with a supermassive black hole but appears to have returned for a second, nearly identical interaction. This striking event, dubbed AT 2022dbl, challenges long-held assumptions about how black holes consume stars and could force a significant rewrite of existing astrophysical models, according to the recent study in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

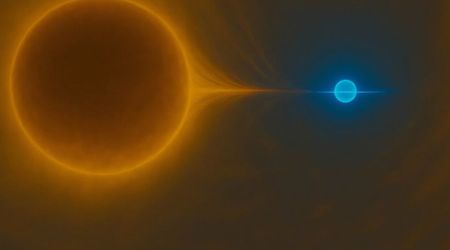

Typically, when a star ventures too close to a supermassive black hole, it's torn apart in a violent process known as a tidal disruption event (TDE), releasing powerful flares that offer rare glimpses into the behavior of these colossal cosmic devourers. However, the repeating nature of AT 2022dbl, with flares occurring 700 days apart, strongly suggests a different scenario. Researchers have ruled out gravitational lensing or two unrelated disruptions as explanations. Instead, the leading theory posits that the initial flare stemmed from a partial disruption of the star, possibly after it was captured through a mechanism known as the Hills mechanism.

The remarkable similarity in energy, temperature, luminosity, and spectral features between both flares, and their consistency with other observed optical-ultraviolet TDEs, raises a profound question: Are many of the optical-ultraviolet TDEs previously thought to be full stellar disruptions actually partial ones? This discovery has significant implications for understanding the physics of accretion and the true nature of black holes. Regardless of whether all or just some of these events are partial disruptions, these findings necessitate a reevaluation of current emission models for optical-ultraviolet TDEs and a recalculation of their expected frequency across the universe.

This pivotal research was led by Dr. Lydia Makrygianni, a former postdoctoral researcher at Tel Aviv University now at Lancaster University in the UK, under the guidance of Prof. Iair Arcavi, who heads the Astrophysics Department at Tel Aviv University and directs the Wise Observatory in Mizpe Ramon. Contributions also came from Prof. Ehud Nakar, Chair of the Astrophysics Department, and Tel Aviv University students Sara Faris and Yael Dgany from Arcavi's research group, alongside a broad network of international collaborators. The findings were officially published in a July issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, as per Phys.org.

The study delves into the enigmatic nature of supermassive black holes, which reside at the core of every large galaxy, boasting masses millions to billions of times that of our Sun. While their existence is confirmed — a discovery that earned the 2020 Nobel Prize for the black hole at the center of our Milky Way — much remains unknown about their formation and their profound influence on their host galaxies. This new research provides crucial insights, potentially reshaping our understanding of these cosmic giants.

Using data from @NASA, @ESA, and ground-based telescopes, scientists found three supermassive black holes at the centers of distant galaxies. They were detected after they pulled apart large stars — ranging between three to 10 times heavier than our Sun — and brightened… pic.twitter.com/QNXLBOJsg2

— NASA Universe (@NASAUniverse) June 5, 2025

One of the greatest hurdles in studying supermassive blackhole is their inherent invisibility; by definition, their immense gravity traps even light. While the black hole at the center of our Milky Way was detected by observing the movement of nearby stars, such detailed observations are impossible for more distant galaxies. Around a black hole, the velocity of the spiraling material approaches the speed of light, generating intense heat and brilliant radiation. These dramatic flares typically illuminate the black hole for weeks to months, offering astronomers a brief window to study its characteristics.

The question now is whether we'll see a third flare after two more years, in early 2026," stated Professor Arcavi. "If we see a third flare, it means that the second one was also the partial disruption of the star. So maybe all such flares, which we have been trying to understand for a decade now as full stellar disruptions, are not what we thought." Should a third flare not materialize, it could indicate that the second flare represented the star's complete disruption. This would imply that partial and full disruptions of stars can appear remarkably similar, a scenario previously predicted by Professor Tsvi Piran's research group at the Hebrew University. "Either way," Arcavi concluded, "we'll have to rewrite our interpretation of these flares and what they can teach us about the monsters lying in the centers of galaxies."