Red supergiant in a nearby galaxy not as close to death as once thought

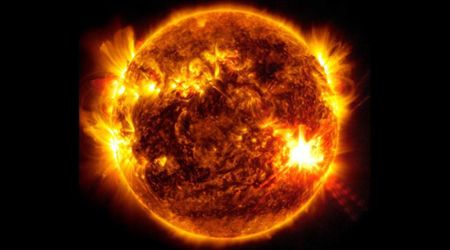

An enormous star in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a nearby galaxy, has recently caught the attention of astronomers. Named WOH G64, it is a red supergiant, and, for a long time, it looked like it was approaching the end of its life by shedding outer cores and growing in size as its nuclear fuel ran out. The star is 1500 times larger than the Sun and pours out over 100,000 times more energy. Astronomers at the UK-based Keele University (KU) who were tracking the star didn’t expect it to die so early because no one has ever witnessed the demise of a red supergiant in their lifetime. But, with the help of the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT), the KU researchers discovered something dramatic and unexpected. The star has grown dimmer and warmer than before. They say that the final stages of the star’s life may be more complicated than previously suspected and report their discovery in a paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“It is a fact that all stars lose mass, no matter their size, age or composition. Stars lose mass as soon as they are born and they continue to lose mass throughout their lives,” writes Jacco Th. van Loon, one of the study authors, in a review paper published in Galaxies. Stars, eight times bigger than the Sun, exhaust fuel within millions of years instead of billions of years because of the massive amounts of energy they release as light. They become cool stars at the end of their life and are christened as red supergiants. Red supergiants blow out gas laden with solid particles like tiny sand grains, also known as dust. Shrouded by such dust, they look dim in visual light but bright in infrared, where dust shines.

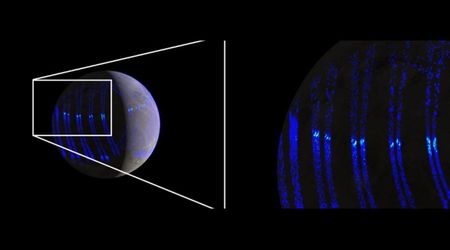

WOH G64 was dismissed as quite unremarkable when it was first discovered in the 1960s, according to The Conversation. However, in the 1980s, thanks to the InfraRed Astronomical Satellite, it revealed itself to be the brightest, coolest, and dustiest supergiant in the Magellanic Cloud. Cut to 2024, the authors of the latest paper and their collaborators in Germany and the US captured a close-up image of the star using the European Southern Observatory’s telescopes. This was the sharpest picture of a star in another galaxy ever taken, which is akin to spotting an astronaut walking on the Moon. They found that, over the preceding decade, the star had begun to shed more dust than before—something that they could not explain at the time. The researchers realized that the ejected dust was also what was possibly responsible for dimming WOH G64. Plus, the star had started to pulsate a little more quickly, indicating it had shrunk. Simultaneously, it also looked warmer, suggesting that it might have entered a new stage of life on its way to its demise—possibly a yellow hypergiant.

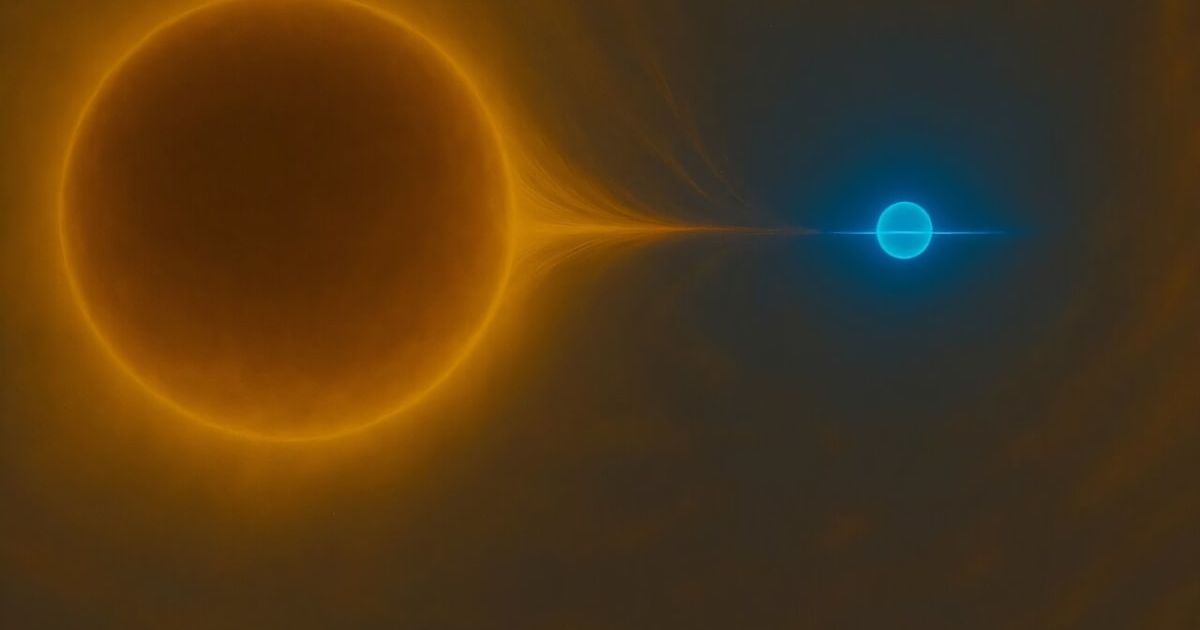

But 2026 observations tell something else. The discovery of an abundance of ions around the star indicates that the gas has been heated up by a hotter star. Additionally, the researchers also found molecules, indicating the presence of cool gas, in what is likely the atmosphere of the supergiant. The observations suggested WOH G64 may not be a yellow hypergiant yet. Scientists had long suspected the presence of a smaller, hotter neighbor in WOH G64's vicinity, and now they cannot ignore it. The smaller one, looking blue in contrast to its bigger, cooler, red sibling, probably heated gas it might have captured from the red supergiant's wind. The gas is more easily detectable now because the supergiant has faded in brightness.

There is a chance that the neighbor got closer recently, stretching the atmosphere of the supergiant, thus making the latter more transparent. This is probably why the warmer interior, with its cool, dark molecular patches, is visible to us. If that is truly the case, then WOH G64 will regain its former red supergiant glory once its neighbor recedes in its orbit. But if its outer layers are completely gone, then we will get a much clearer view of the star.

More on Starlust

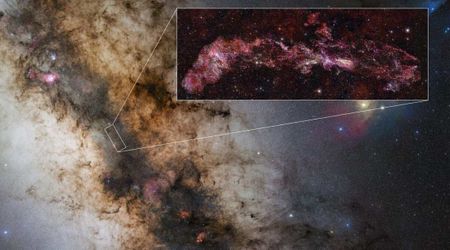

What triggers massive Milky Way stars to run away from their birthplaces?

A black hole belching out the remains of a star it ate is emitting more energy than the 'Death Star'