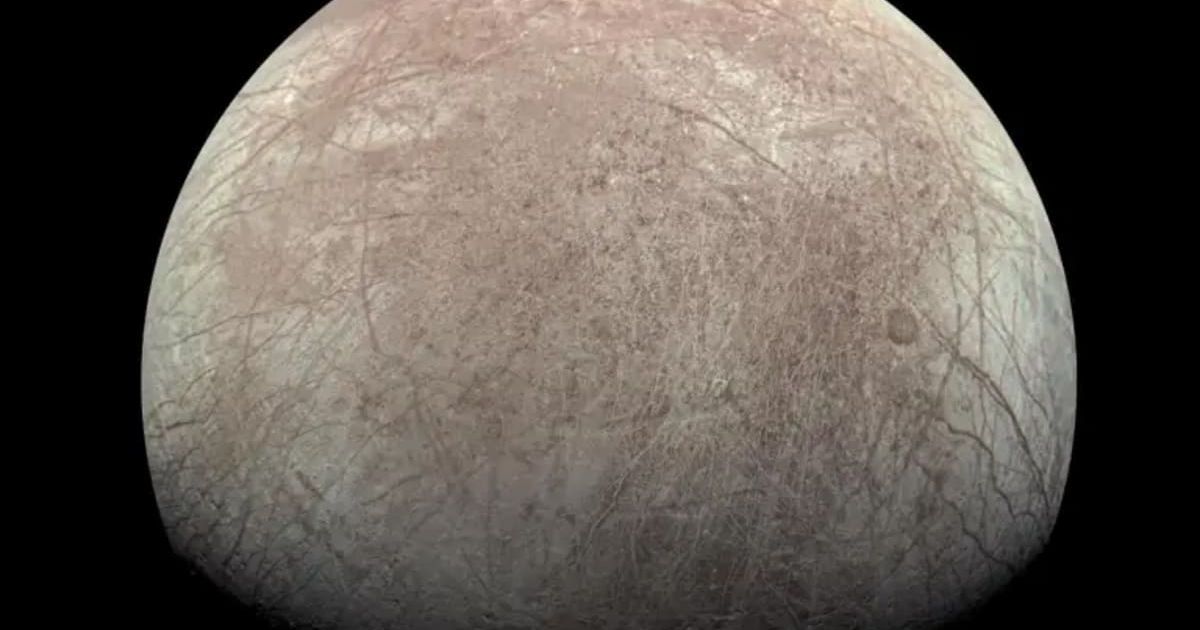

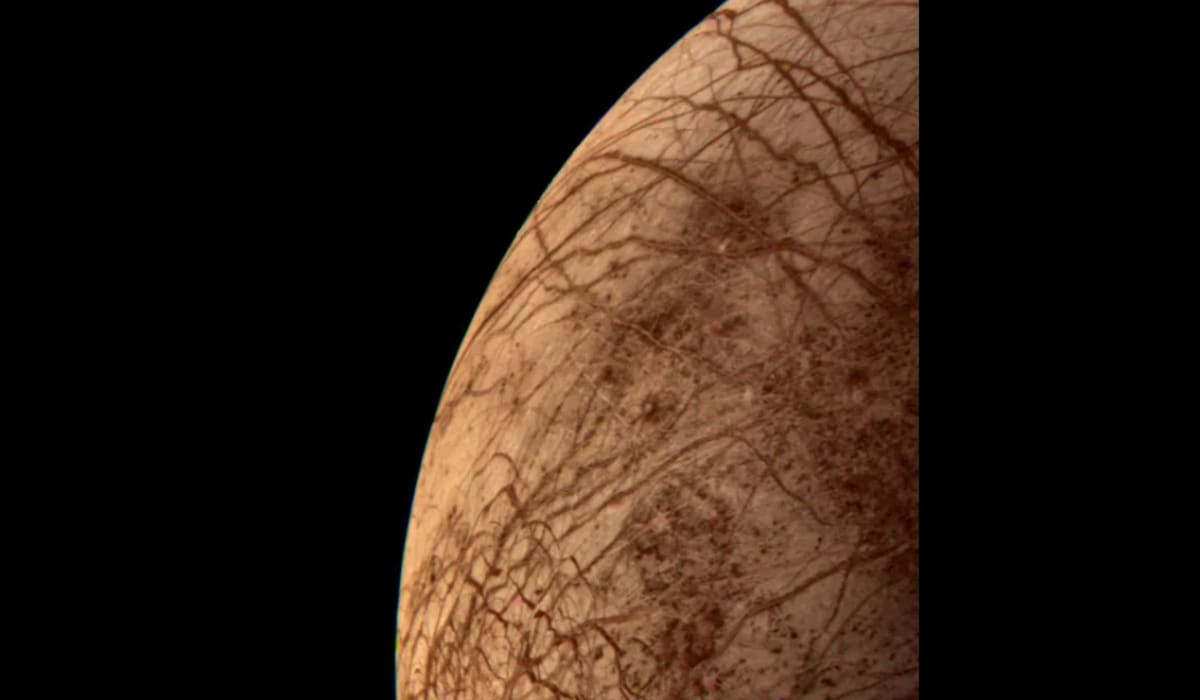

New study shows how Jupiter's moon Europa gets life-supporting nutrients for its ocean

The subsurface ocean of Jupiter's moon Europa is one of the hottest candidates for microscopic extraterrestrial life in the solar system. That being said, scientists have long scratched their heads over how nutrients essential for life could make their way from the surface to the ice-covered body of water. Well, geophysicists from Washington State University may have figured out how.

While Europa has more liquid water than all of Earth's oceans put together, the problem is that it lies beneath a thick shell of ice that doesn't let sunlight in. This means that life in Europa's ocean has to depend on energy sources not named the Sun, which raises questions as to how the ocean could be conducive to life at all. Then there's the thing about Jupiter's radiation. It interacts with salts and minerals in Europa's surface, creating useful nutrients for oceanic microbes. Despite several theories, however, scientists did not have a clear idea about how these nutrients from the surface could reach the ocean below. Yes, thanks to Jupiter's gravitational pull, Europa's icy surface is quite active. But then again, the ice mostly moves sideways rather than vertically, thereby imposing limits on the chances of crucial surface-ocean exchange.

To find a solution to this problem, the researchers used computer modeling based on crustal delamination, a process that sees a part of Earth's crust get "tectonically squeezed and chemically densified" to the point that it becomes so heavy that it just sinks into the mantle below. "This is a novel idea in planetary science, inspired by a well-understood idea in Earth science," explained Austin Green, the lead author of the study published in The Planetary Science Journal and a postdoctoral researcher at Virginia Tech, in a statement. "Most excitingly, this new idea addresses one of the longstanding habitability problems on Europa and is a good sign for the prospects of extraterrestrial life in its ocean."

It's because of the fact that several regions of the icy shell on Europa are covered in densifying salts that the researchers thought that this process might apply to it. The study proposed that parts of the ice that is more dense and saltier than their surroundings would descend into the shell's interior, thereby creating opportunities for surface-ocean exchange. In fact, the computer modeling demonstrated that the nutrient-rich ice could sink all the way down to the base, irrespective of salt content, given that the surface ice is weakened to some degree. This process is quite rapid and may be a consistent way of recycling and of supplying Europa's ocean with nutrients necessary for life.

Europa will be studied with greater depth by NASA's Europa Clipper, which was launched in 2024. Set to arrive in April 2030, it will conduct nearly 50 close flybys of the moon over the span of 4 years in order to measure the depth of the subsurface ocean and to assess its habitability.

More on Starlust

Mysterious weather patterns of Jupiter and Saturn's poles reveal secrets about their interiors