NASA astronomers warn explosive satellite growth poses 'a very severe threat' to space telescope data

In just the first two days of December this year, Elon Musk’s SpaceX launched as many as 85 satellites into low Earth orbit, with more such liftoffs scheduled over the coming days. While it is a testament to the massive strides space technology has taken over the course of just a few years, it’s the flip side of the coin that is bothering NASA astronomers. A study published in the journal Nature has become the first to estimate how the sheer number of satellites that will be launched over the years could come in the way of space telescopes looking to uncover the mysteries of the universe.

Falcon 9 launches 29 @Starlink satellites from Florida pic.twitter.com/ZK45slRCc5

— SpaceX (@SpaceX) December 1, 2025

Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation constitutes a major portion of the population of low Earth orbit satellites that has grown from around 2,000 to 15,000 since 2019. And if all the launches filed to regulators are successful, the number will reach a massive 560,000 satellites by the end of the 2030s. The researchers simulated how the population of more than half a million satellites would impact four space telescopes. The results were worrying to say the least, with lead author, Alejandro Borlaff of the NASA Ames Research Center, issuing the warning of “a very severe threat,” per Phys.org.

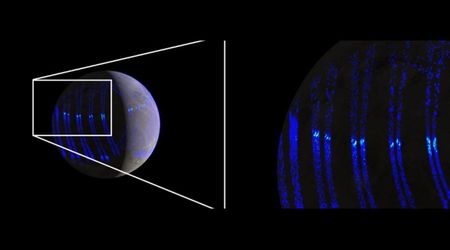

The study concluded that no less than 96% of all the images obtained by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) planned ARRAKIHS telescope, the Xuntian telescope planned by China, along with those taken by NASA’s SHEREx, which is already active, will be corrupted by the light reflecting off satellites. By comparison, the Hubble Telescope will have a third of its images tainted because a satellite is less likely to come within its relatively narrower field of view. On the other hand, some space telescopes, like the James Webb, are safe because they hover at a stable spot called the second Lagrange point, which is 1.5 million kilometers (932,000 miles) from our planet.

Regardless of the level of impact on each telescope, the seriousness of the implications cannot be overstated. "Imagine that you are trying to find asteroids that may be potentially harmful for Earth," Borlaff said, reminding that an asteroid hurtling through the sky can hardly be differentiated from a satellite. “It's really hard to figure out which one is the bad one," he added. While one solution could be to lower the deployment altitudes of satellites to below those of space telescopes, the move could deplete Earth’s ozone layer. We could just launch fewer satellites, but competition among satellite internet companies, plus the demands being made by the ongoing AI boom, do not make that a likely scenario.

Granted, Musk’s Starlink makes up for nearly three-quarters of the current satellite population, but the growing competition will see it account for just about 10% of the total number in a couple of decades. Plus, Starlink has been making conscious efforts to reduce the brightness of its satellites. For instance, the second generation of the company’s satellites, launched in 2023, came fitted with a “dielectric mirror film” that was designed to scatter sunlight away from Earth.

Developed in-house, the dielectric mirrors on the surface of the satellites and extremely dark black paint for angled surfaces or those not conducive to mirror adhesion help absorb and redirect light away from the ground https://t.co/BXmfpIG495

— Starlink (@Starlink) September 16, 2023

But whether such efforts would actually bear any fruit is a huge question mark, given that satellites are growing bigger with time. Those that are about 100 square meters are already “as bright as the brightest of stars,” Borlaff said. Now, with the growing demands of AI data, there are plans to build satellites as big as 3,000 square meters. Borlaff warned that those will be “as bright as a planet.”

More on Starlust

SpaceX deploys 29 Starlink satellites to low Earth orbit, completing third batch in two days

NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope survives another round of tough space tests