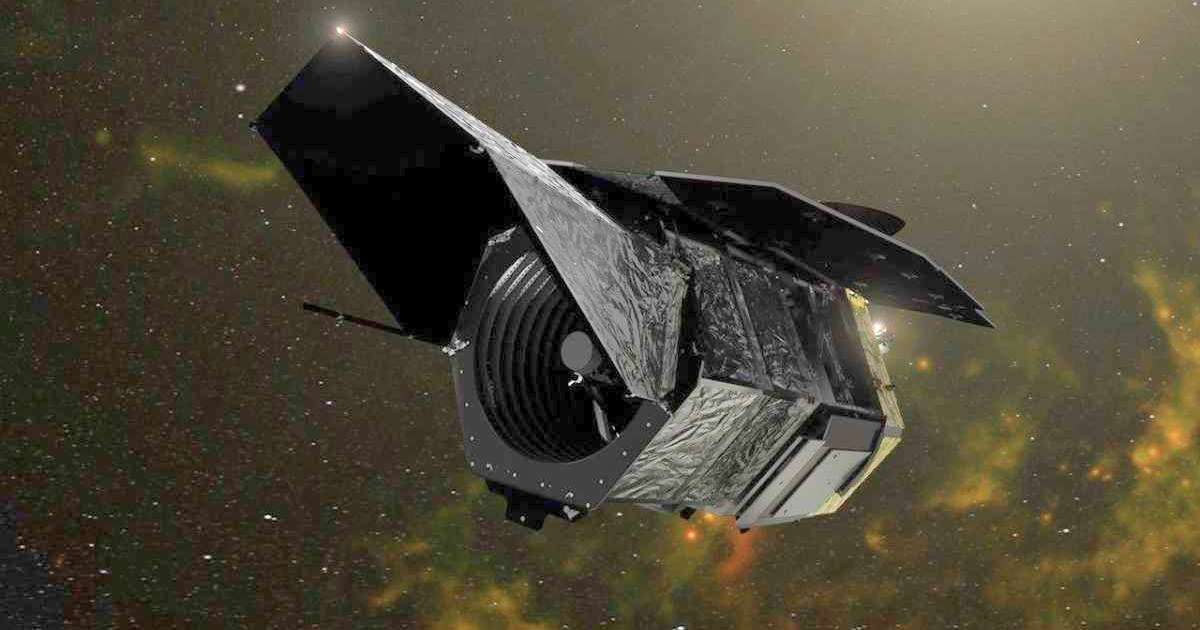

NASA's Roman Telescope to map dark matter and dark energy more precisely than ever

Since the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990, NASA has sent many great telescopes into space. The latest up its sleeve is the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, whose gaze will survey the endless voids of space and zoom in on hundreds of millions of galaxies across the universe. Scheduled to fly this fall, its roving eye will unveil the secrets of dark, deep recesses of the cosmos and help scientists better understand dark matter and dark energy. “We set out to build the ultimate wide-area infrared survey, and I think we accomplished that,” said Ryan Hickox, a professor at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and co-chair of the committee that shaped the survey’s design, in a statement released by NASA. “We’ll use Roman’s enormous, deep 3D images to explore the fundamental nature of the universe, including its dark side.”

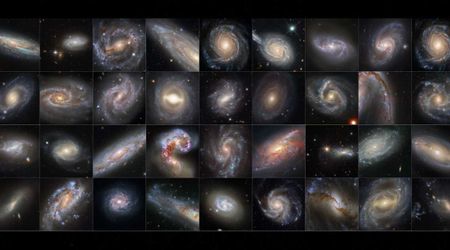

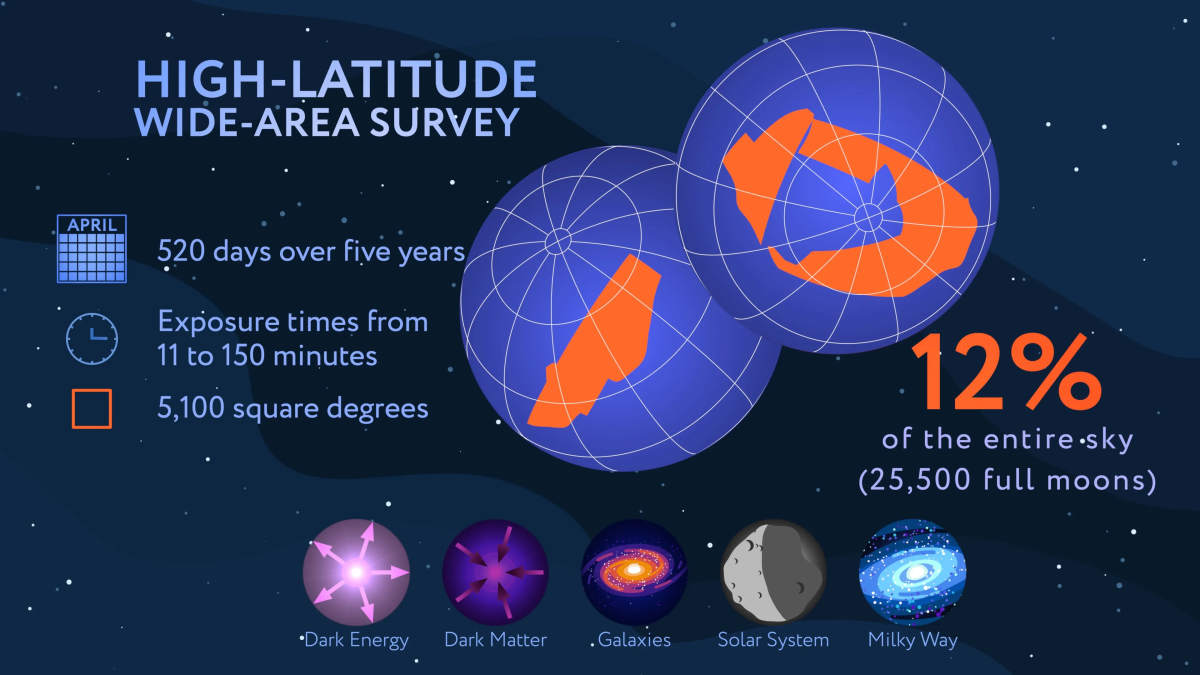

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, supported by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and a team of scientists from various other research institutions, looks after the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Its High-Latitude Wide-Area Survey (HLWAS) program will cover nearly 12 percent of the sky in less than two years. Roman will look far beyond the dusty plane of our Milky Way galaxy, giving the clearest view of the distant cosmos. “This survey is going to be a spectacular map of the cosmos, the first time we have Hubble-quality imaging over a large area of the sky,” said David Weinberg, an astronomy professor at Ohio State University in Columbus, who played a major role in devising the survey.

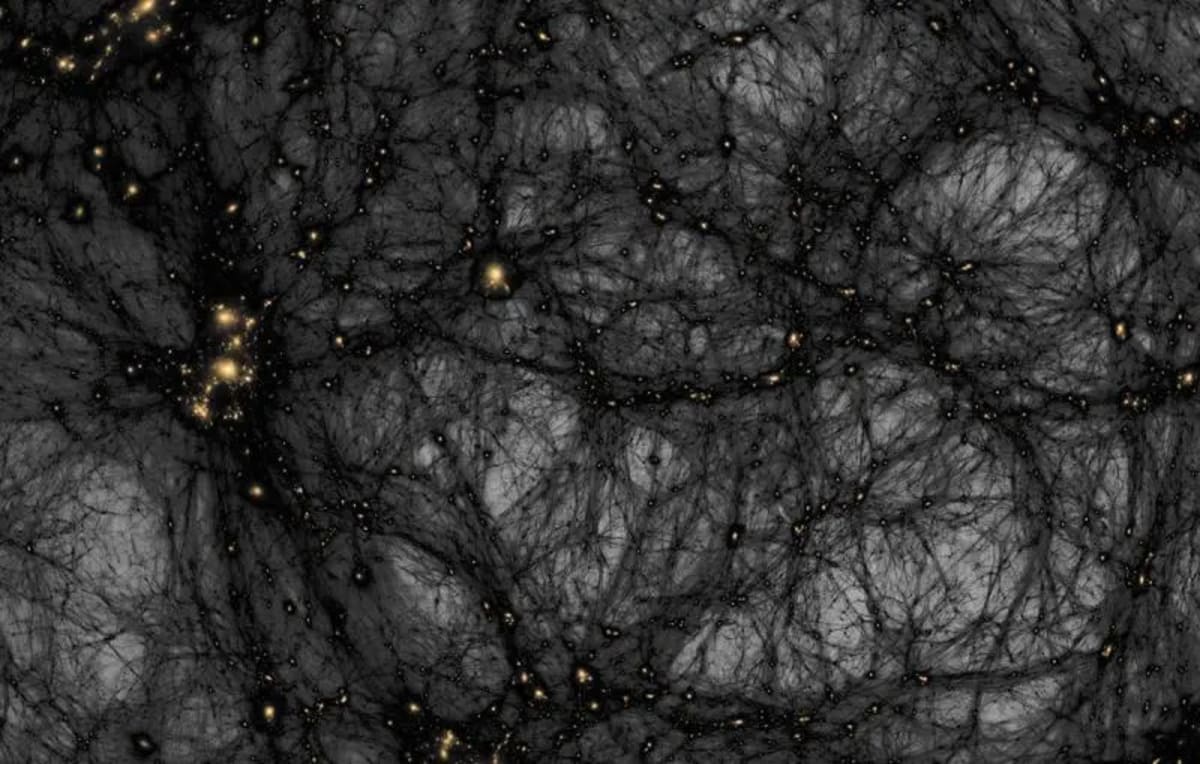

“Even a single pointing with Roman needs a whole wall of 4K televisions to display at full resolution. Displaying the whole high-latitude survey at once would take half a million 4K TVs, enough to cover 200 football fields or the cliff face of El Capitan,” Weinberg added. Roman will use its imaging and spectroscopic devices to explore invisible dark matter, which can only be detected via its gravitational effects on other objects, and dark energy, the pressure under which the universe is expanding. Moreover, Roman's wide field of view will give it an edge in studying even small-scale gravitational lensing, thus allowing researchers to see how dark matter clumps warp how distant galaxies look.

Hickox said, “Weak lensing distorts galaxy shapes too subtly to see in any single galaxy—it’s invisible until you do a statistical analysis.” He went on to add that at least 600 million of the billion galaxies that Roman will see will be detailed enough to study the effects of weak gravitational lensing. "Roman will trace the growth of structure in the universe in 3D from shortly after the Big Bang to today, mapping dark matter more precisely than we’ve ever done before." Roman’s wide-area survey will also gather spectra from around 20 million galaxies. Analyzing the spectra will reveal how the universe has expanded over ages because light from receding objects shifts towards redder wavelengths as the distance increases. This phenomenon is called redshift, and astronomers will make sure of this to create a 3D map of all galaxies as far as 11.5 billion light-years away.

This, in turn, will lead astronomers to the frozen ripples of the primordial sound waves that traversed the early universe. These ripples, which house more galaxies than anywhere else, act "like a ruler for the universe," per NASA, and are about 500 million light-years wide today. Roman will measure their size across cosmic eras and how dark energy may have evolved. “Roman’s imaging survey combined with its redshift survey give us new information about the evolution of the universe—both how it expands and how structures grow with time—that will help us understand what dark energy and gravity are doing at unprecedented precision,” explained Risa Wechsler, director of Stanford University’s KIPAC (Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology) in California and co-chair of the committee that shaped the survey’s design.

More on Starlust

Dark matter powers the Milky Way’s heart instead of a black hole, new study claims

James Webb Telescope's new map is strong proof that there would be no life without dark matter