NASA's Juno finds that Jupiter isn't as big as previously thought

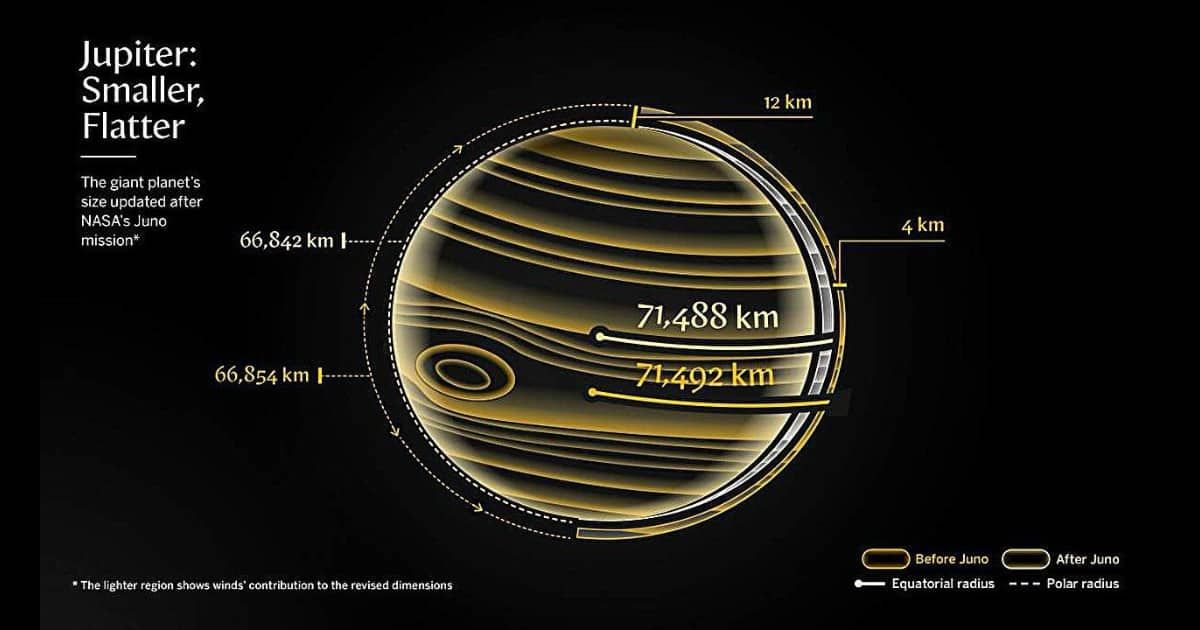

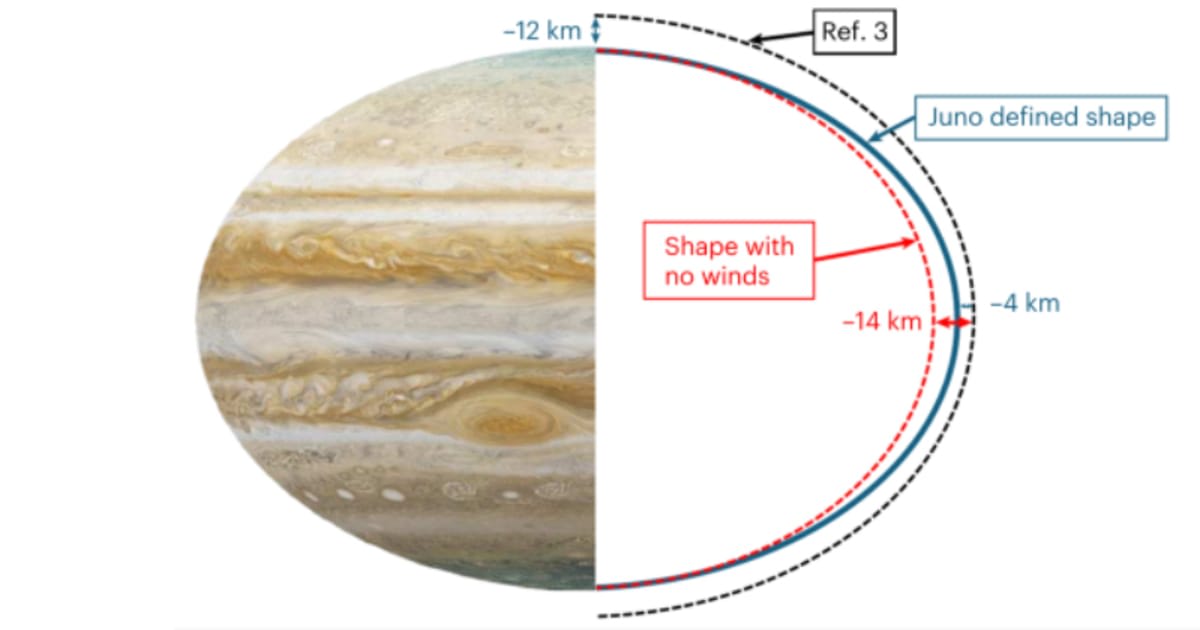

NASA has updated Jupiter’s dimensions using data from its Juno spacecraft, revealing the gas giant is smaller and flatter than long-held estimates suggested. New measurements at the 1-bar pressure level show an equatorial radius of 44,429 miles (71,488 km) and a polar radius of 41,552 miles (66,842 km). The radii were found to be roughly 2.5 miles (4 km) and 7.5 miles (12 km) smaller, respectively, than figures from nearly 50 years ago. These precise values, published on February 2, 2026, in a paper titled ‘The size and shape of Jupiter’ in Nature Astronomy, were obtained by analyzing radio signals bent by Jupiter’s exotic atmosphere during 13 Juno flybys since 2016. Uncertainties dropped to just 0.25 miles (0.4 km) by factoring in powerful zonal winds, which prior methods of determining Jupiter’s dimensions had ignored.

The redefined shape reshapes Jupiter’s interior models, supporting a metal-rich, cooler atmosphere, thereby reconciling gaps between Galileo probe data, Voyager temperatures, and computer models. Winds above cloud tops are mostly barotropic, shifting little by altitude, which, according to the study, was the feature of the banded storms on the visible surface. For exoplanet hunters at observatories around the world, Jupiter’s true size will now serve as a new benchmark for models of distant gas giants when they are observed transiting their host star.

Earlier measurements came from NASA’s Voyager mission, which is still operational, and Pioneer probes’ radio occultations in the 1970s, using just six passes with 2.5-mile (4 km) uncertainties and little to no wind considerations. Those pegged Jupiter as being, in relative terms, slightly larger than it really was. Earlier measurements of the Jovian radius came in at 44,423 miles (71,492 km) at the equator and a radius of 41,541 miles (66,854 km) at the poles.

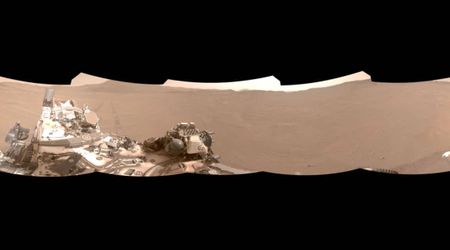

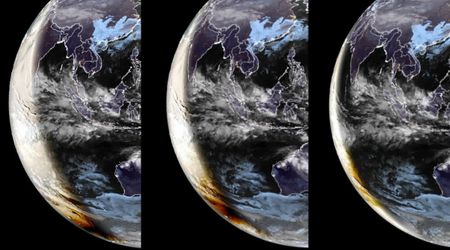

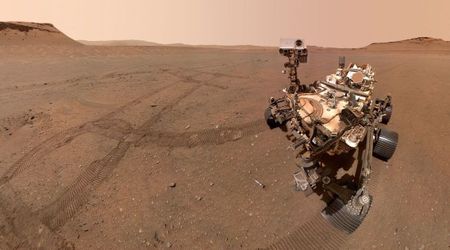

NASA’s Juno, orbiting Jupiter since 2016, has served as the source of numerous data points for research about Jupiter, employing radio occultations for this breakthrough. Generally, occultations happen when a bright object like our sun or a star passes behind a smaller body, say, a planet, its atmosphere, its rings, or a moon. This gives the observer an opportunity to study the characteristics of a planet’s atmospheric contents or its shape and size against the change in the properties of the light passing through. Astronomers also use these events to determine the angular diameters of stars, detect binary star systems, and determine the precise shapes of asteroids. For this study, radio occultations were employed, with Juno transmitting signals through Jupiter’s atmosphere toward Earth via SCaN‘s Deep Space Network, the same method used for communications with Artemis II astronauts in deep space, as the gas giant passes between the spacecraft and our own. This bent the radio waves in ways that helped figure out atmospheric density, temperatures, and the exact boundaries of the planet’s oblate form at specific pressure levels.

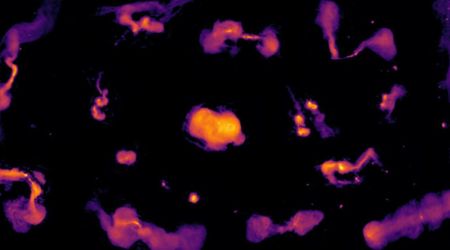

This method offers a unique window into otherwise hidden layers, far beyond what previous observations could achieve. Through these occultations, Juno not only helped refine calculations of Jupiter’s dimensions but also ended up doing a lot more in that time, such as shedding light on intricate polar cyclone clusters in the atmosphere, with all this data streamed back in time to the mission’s operations hub at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Meanwhile, NASA’s Galileo mission, launched in 1989 and arriving at Jupiter in 1995, dropped an atmospheric probe into the Jovian clouds so as to study their composition, while itself providing data for years until 2003.

More on Starlust

Jupiter has more oxygen than the Sun, new study finds

NASA’s Juno spacecraft reveals new details about the thickness of Europa’s icy shell