James Webb Telescope solves 20-year cosmic mystery, finds evidence of 'monster stars' from early universe

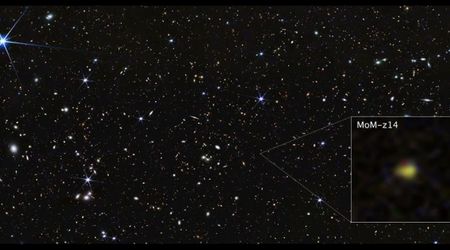

For twenty years, astronomers have been scratching their heads over a big puzzle about how supermassive black holes, some of the brightest objects out there, showed up less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Normal stars just don’t grow fast enough to make black holes that huge in such a short time. Now, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope has given us a major clue.

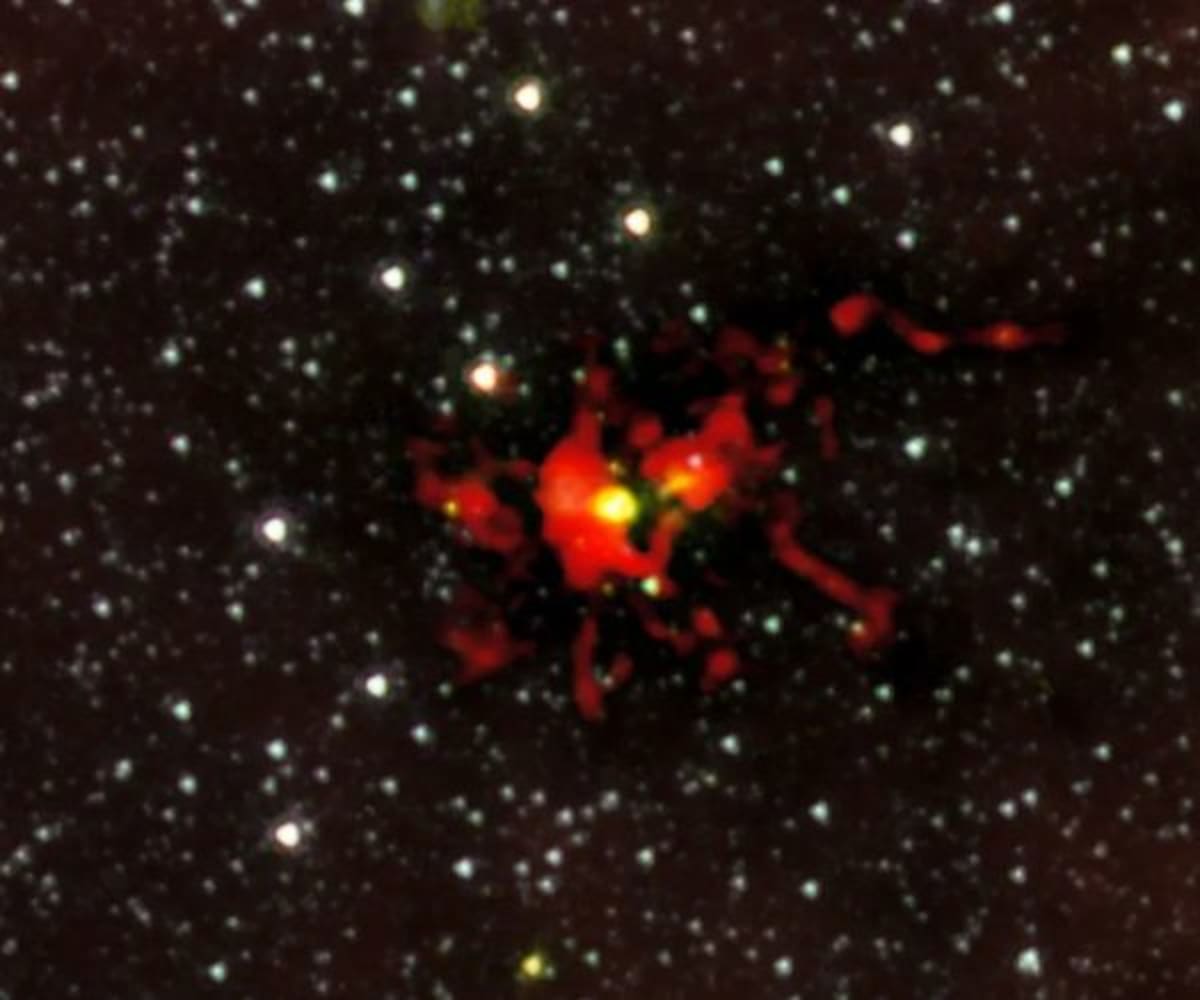

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, a team comprising researchers from the University of Portsmouth and the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard and Smithsonian, found evidence that “monster stars," of masses up to 10,000 times greater than our Sun, actually existed in the early universe. They spotted it by looking at a distant galaxy called GS 3073. Their attention was caught by a weirdly high nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio of 0.46. No ordinary stars or explosions we know about can make that kind of mix. Dr. Daniel Whalen from Portsmouth put it simply in a statement: “Our latest discovery helps solve a 20-year cosmic mystery. With GS 3073, we have the first observational evidence that these monster stars existed.” These giant stars would have burned incredibly bright but only for a short time, about a quarter-million years, which is nothing in cosmic terms.

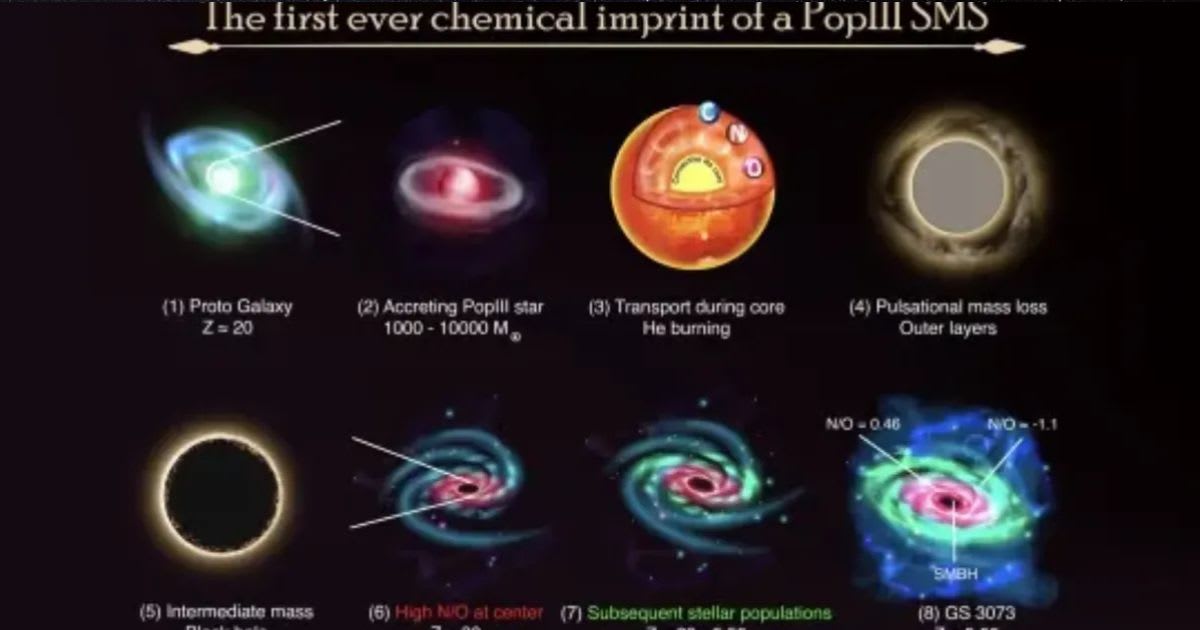

But how do they produce such massive amounts of nitrogen? These beasts burn helium in their cores, making carbon. That carbon mixes with hydrogen in a shell around the core and, through a process called the CNO cycle, turns into nitrogen. Convection swirls it all around, and eventually the star sheds this nitrogen-rich material into space. When the team ran computer models of stars between 1,000 and 10,000 times the Sun’s mass, the numbers matched what they saw in GS 3073.

Smaller or bigger stars didn’t produce the same pattern. There’s a sweet spot right in that monster range. What’s even more amazing is that GS 3073 has an active black hole at its center right now. It could be the leftover core of one of these supermassive stars that collapsed billions of years ago. Back in 2022, it was predicted that these monster stars could form in special streams of cold gas in the early universe, thereby explaining the existence of extraordinarily bright black holes (quasars) at the time.

Now they’ve found the chemical fingerprint to prove it. Dr. Devesh Nandal from Harvard said the chemical mix is like a cosmic fingerprint. “The pattern in GS 3073 is unlike anything ordinary stars can produce. It matches only one kind of source, primordial stars thousands of times more massive than our Sun.”

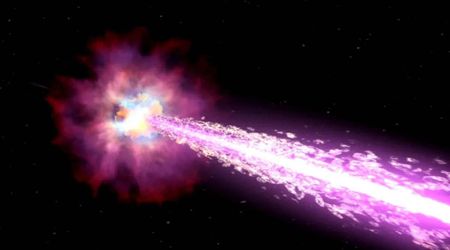

The models, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, also predict what happens when these monster stars die. Instead of exploding, they collapse directly into massive black holes weighing thousands of solar masses. The researchers think JWST will spot more galaxies with this same nitrogen overload as it keeps looking deeper into the early universe. Each one would be another piece of proof that these cosmic giants really existed.

More on Starlust

Astronomers image rare Tatooine-like world orbiting two suns locked in 300-year cycle