It's possible to find Earth 2.0 using rectangular telescope about the same size as JWST, scientists say

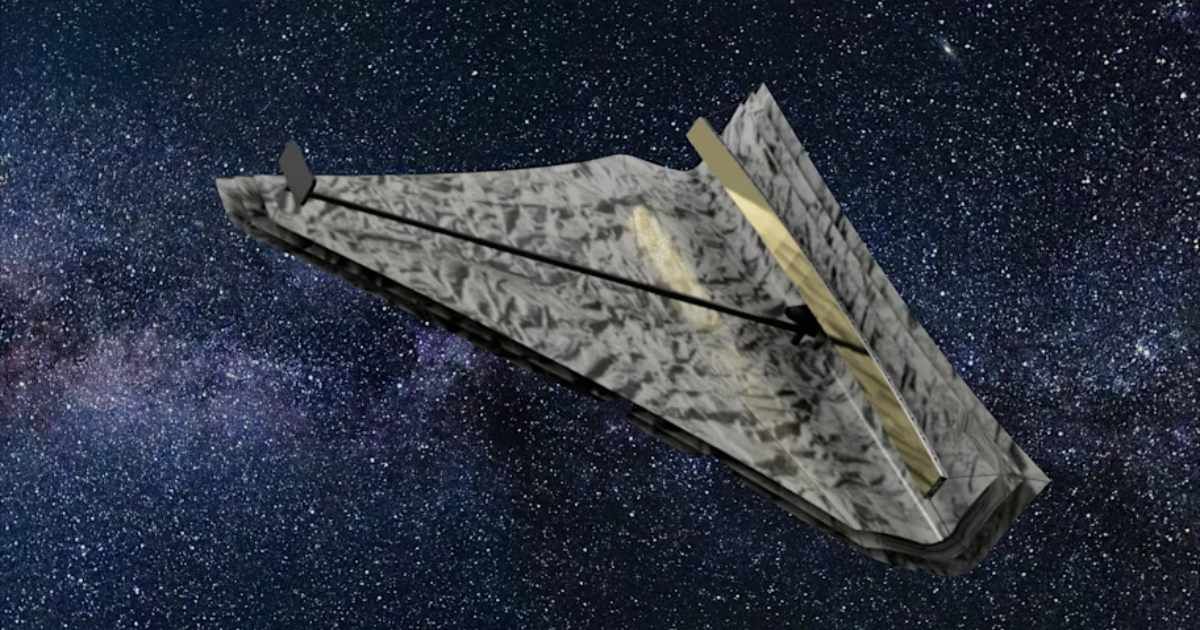

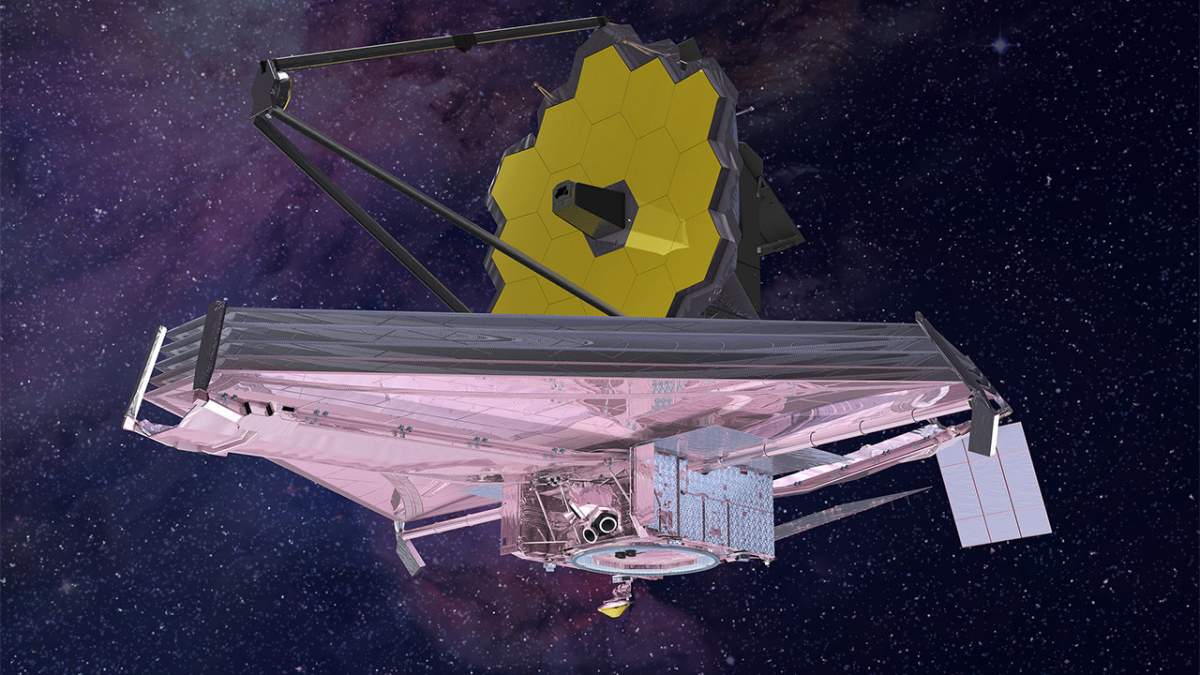

A new study suggests that a specially-designed rectangular telescope could be the key to finding another Earth. Scientists propose that a space telescope with a 1 by 20-meter mirror, similar in size to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), could effectively locate habitable planets orbiting sun-like stars, as per Frontiers. Published in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, the research from astrophysicist Heidi Newberg and her team at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute outlines how a rectangular mirror could overcome the significant challenges of spotting distant exoplanets.

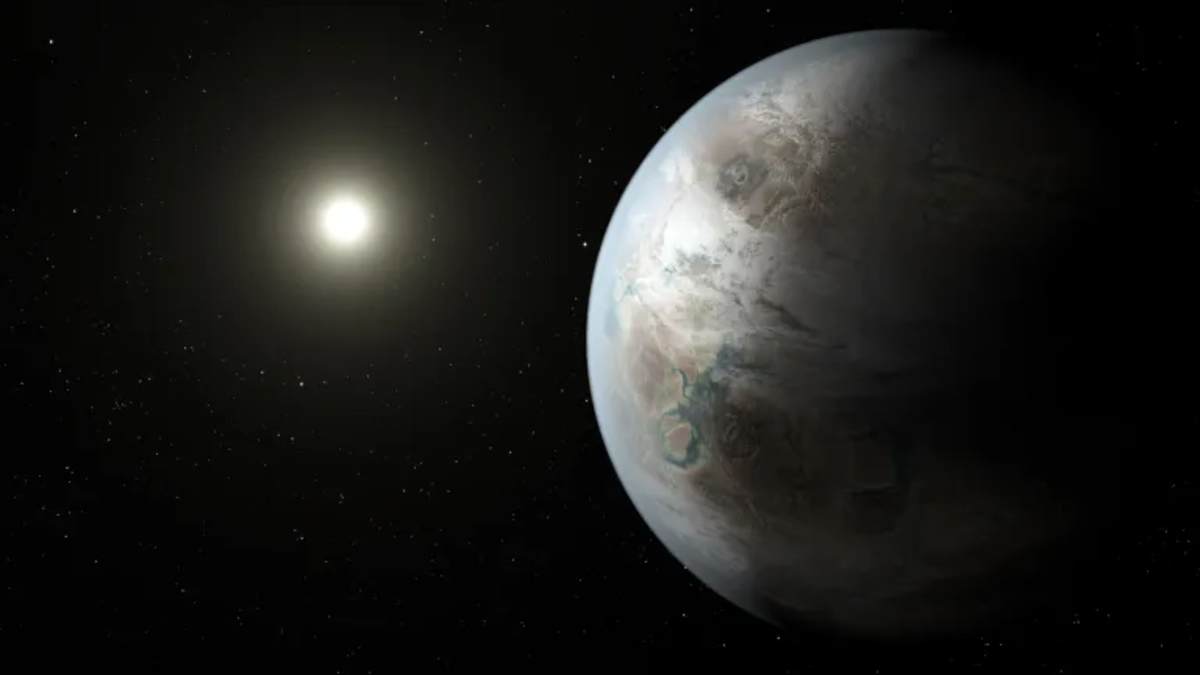

Finding an exoplanet that is similar to Earth is a monumental task. The primary obstacle is the immense brightness of the host star, which can be up to one million times more luminous than its planet. Current telescopes struggle to get a clear image because the light from the star and the planet blur together. To overcome this, a space telescope operating at infrared wavelengths would need a mirror at least 20 meters wide to achieve the necessary resolution, a size considered unfeasible with today's technology.

Previous solutions, such as launching multiple smaller telescopes in a precise formation or using a separate "starshade" spacecraft to block starlight, are also hampered by technological limitations. While using visible light could allow for a smaller telescope, the star's brightness becomes a staggering 10 billion times greater, making it virtually impossible to isolate the planet's light.

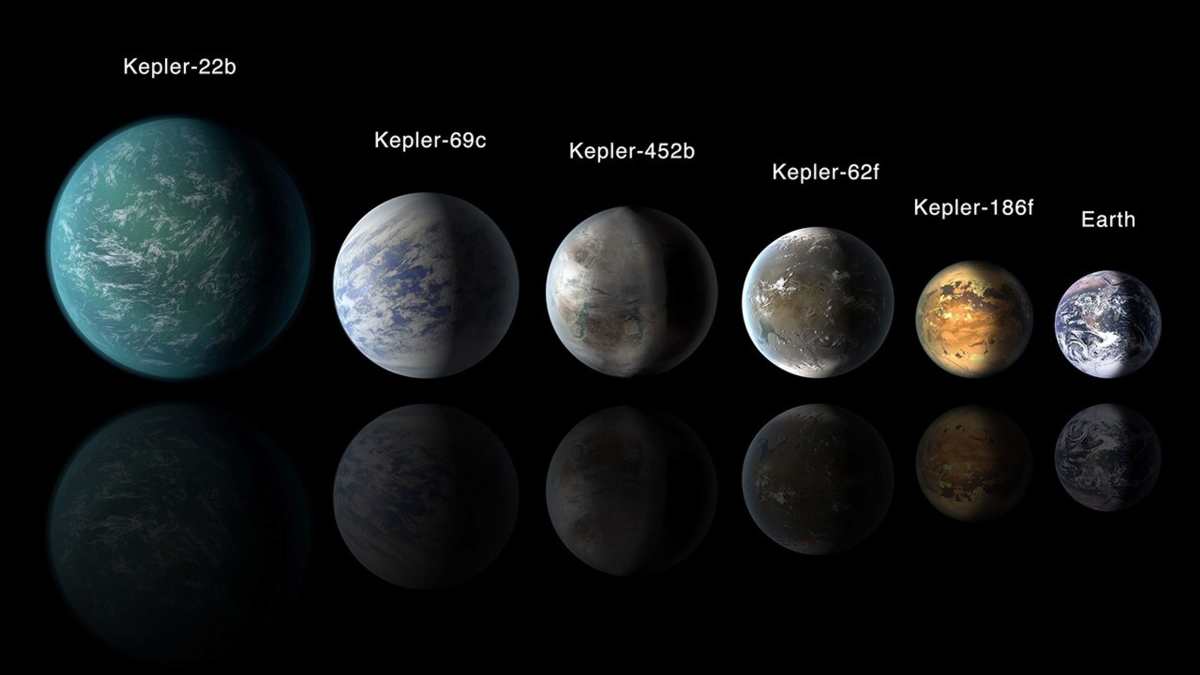

The proposed rectangular telescope offers a more attainable path. The design allows the telescope to separate a star from a planet in the direction of the mirror's longest axis. The telescope could simply be rotated to align with the planet's orbit. The researchers believe that this design, with a mirror about the same size as JWST, could find roughly half of all existing Earth-like planets within a 30-light-year radius in under three years. If there's an average of one Earth-like planet per sun-like star, the telescope could identify around 30 promising candidates for further study.

The findings suggest that the rectangular telescope could be a viable and practical next step in the quest for "Earth 2.0." The design requires no major technological breakthroughs and could provide a direct route to identifying planets with atmospheres that show signs of life, potentially paving the way for future missions to explore them. The potential to discover "Earth 2.0" using a more feasible telescope design is a significant step toward answering one of humanity's oldest questions: "Are we alone?" This research could provide a practical pathway to identifying potentially habitable planets, offering a chance to find life beyond our solar system and inspiring future generations to explore the cosmos.

In related findings, new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope are providing a clearer picture of the exoplanet K2-18 b. While previous studies suggested a habitable world, the latest data show a water-rich planet but cast doubt on earlier hints of a habitable environment. The new observations, which reveal the presence of methane and carbon dioxide in the planet's atmosphere, support the idea that it is a "Hycean" world, a planet with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere and a vast, liquid water ocean. However, the data from JWST's Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) does not strongly support the presence of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a gas that on Earth is produced almost exclusively by living organisms.

More on Starlust

Earth-like exoplanet 41 light-years away has no atmosphere to support life, new JWST data reveals