Four baby planets reveal the cosmic recipe behind super-Earths and sub-Neptunes

![Artist’s illustration of the V1298 Tau planetary system. [Representative Cover Image Source: R. Hurt, K. Miller(Caltech/IPAC)]](https://d3hedi16gruj5j.cloudfront.net/786462/uploads/dc6395c0-ec53-11f0-90fb-df3e0493b923_1200_630.jpeg)

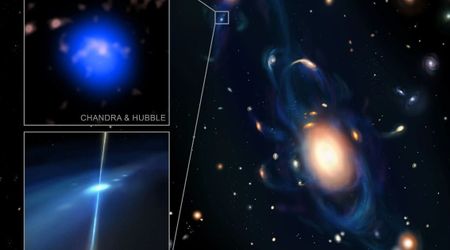

Scientists have long been puzzled by one of the universe’s most common planetary types. Across the Milky Way, planets slightly larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune appear around most stars. Yet our own solar system has none. That absence has made it difficult to understand how these worlds form and evolve. A team of astrophysicists, however, put an end to the frustration when they observed four extremely young planets orbiting a young star designated V1298 Tau. These planets are still in their infancy, but are evolving into the most common type of planets we know of. The findings, published in the journal Nature, offer one of the clearest explanations yet of how these common planets take shape.

“I’m reminded of the famous ‘Lucy’ fossil, one of our hominid ancestors that lived 3 million years ago and was one of the ‘missing links’ between apes and humans,” said UCLA professor of physics and astronomy and the second author, Erik Petigura, in a statement. “V1298 Tau is a critical link between the star- and planet-forming nebulae we see all over the sky, and the mature planetary systems that we have now discovered by the thousands.” V1298 Tau is a very young star, just about 20 million years old. Compared to our Sun’s age of 4.5 billion years, that makes it a cosmic newborn. In human terms, researchers liken it to a five-month-old baby. Orbiting this young star are four large planets, each currently between the sizes of Neptune and Jupiter.

But unlike growing infants, these planets are doing the opposite. Instead of expanding, they are contracting. “What’s so exciting is that we’re seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system,” said John Livingston, the study’s lead author from the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo, Japan. “The four planets we studied will likely contract into ‘super-Earths’ and ‘sub-Neptunes’—the most common types of planets in our galaxy, but we’ve never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.” Planets are born in swirling disks of gas and dust that surround young stars. This early phase is chaotic, lasting hundreds of millions of years, and planets can gain or lose mass rapidly. Until now, scientists did not know why so many planets ended up in the narrow size range between Earth and Neptune.

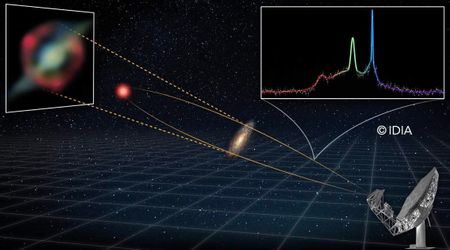

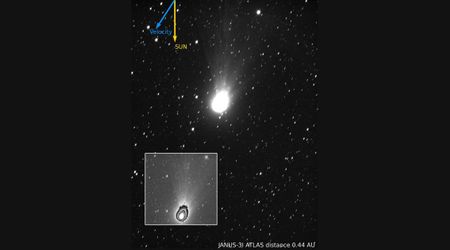

To uncover what was happening around V1298 Tau, the research team tracked the planets as they passed in front of their star. These observations came from a mix of ground-based and space-based telescopes and spanned nearly ten years. The process was far from straightforward. “We had two transits for the outermost planet separated by several years, and we knew that we had missed many in between. There were hundreds of possibilities which we whittled down by running computer models and making educated guesses,” said Petigura. The breakthrough came unexpectedly. “Hey, we got it from the ground!” Livingston wrote in a Slack message after capturing another crucial transit. “I couldn’t believe it! The timing was so uncertain that I thought we would have to try half a dozen times at least. It was like getting a hole-in-one in golf,” said Petigura.

With the orbital timing finally nailed down, the team could measure how the planets tugged on one another through gravity. This allowed them to calculate the planets’ masses for the first time. The results were surprising. Although the planets are 5 to 10 times wider than Earth, they are only 5 to 15 times more massive. That means they are extremely low-density. “The unusually large radii of young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured,” said Trevor David, a co-author from the Flatiron Institute who led the system’s discovery in 2019. “By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally ‘puffy,’ which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

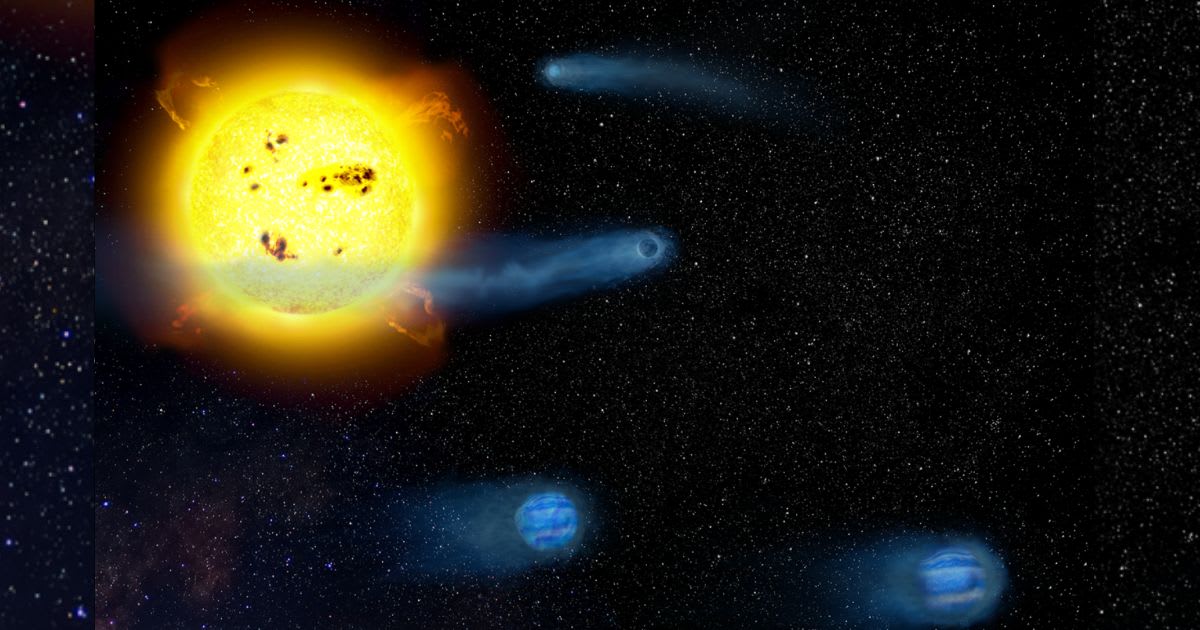

![An illustration depicting the Sun-like star Kepler 51 and three giant planets with extremely low density that NASA's Kepler space telescope discovered in 2012-2014. [Representative Image Source: NASA/ESA/L. Hustak/J. Olmsted/D. Player and F. Summers (STScI)]](https://de40cj7fpezr7.cloudfront.net/71e3cc0e-8c03-44a6-ab8a-b9c6ef103d30.jpg)

“Our measurements reveal they are incredibly lightweight, some of the least dense planets ever found. It’s a critical step that turns a long-standing theory about how planets mature into an observed reality,” said Livingston. Further modeling shows that these planets have already lost much of their original atmospheres and will continue to shrink for billions of years. By catching four planets mid-transformation, astronomers now have their clearest recipe yet for how some of the most common worlds in the universe are made.

More on Starlust

Astronomers find the earliest, hottest galaxy cluster that should not exist: 'Too strong to be real'

NASA's JWST reveals ancient monster stars that could be the ancestors of black holes