Bacteria on Mars may hold the key to future human habitats on the planet

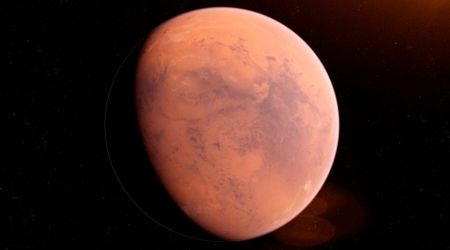

Humans have set foot on the Moon. Their next stop is Mars. The Red Planet, once draped in a thick atmosphere, now has thin air rich in carbon dioxide that thaws by day and freezes at night. Moreover, constant cosmic radiation makes its environment even more unforgiving and hostile to life. Then there is the distance. At around 140 million miles from Earth, a trip to Mars might take three years. So, it is difficult for a spaceship to bring everything from Earth to set up a human colony on the planet. But what is the way out? A research team that led by Shiva Khoshtinat, a postdoc at the Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering 'Giulio Natta' at Politecnico di Milano, has come up with a solution through its research that was published in Frontiers in Microbiology.

They say that help may come from microbes, the silent engineers that shaped Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago, turning its hostile environment into a habitable place for life to emerge and evolve. Growing in shallow pools and seas, those microbes transformed Earth’s environment through biomineralization—a process through which microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and microalgae produce minerals as part of their metabolism. These microorganisms that can thrive in extreme environments like acidic lakes, volcanic soils, and deep caves may reveal the versatility needed for Martian adaptation. Guided by Mars rovers’ data about Martian soil composition, the researchers explored multiple microbial mineralization pathways. Their aim was to discover which one can help make strong building materials for Mars habitats without posing an interplanetary pollution risk.

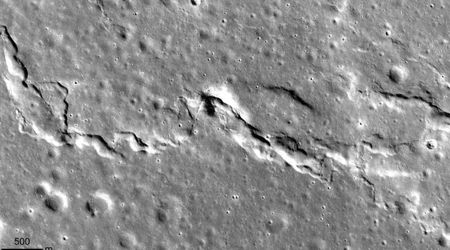

They screened microbes with the potential to produce minerals. They found that microorganisms that generate natural cement-like materials, such as calcium carbonate, at room temperature are the most promising. They narrowed their search to two remarkable bacteria: Sporosarcina pasteurii, a well-known bacterium that produces calcium carbonate via ureolysis (breakdown of urea by bacteria into ammonia and carbon dioxide), and Chroococcidiopsis, a resilient cyanobacterium known for surviving extreme environments, including simulated Martian conditions. The researchers say that this bacterial co-culture mixed with Martian regolith can act as feedstock for 3D printing building materials on Mars. According to them, such microbial life could exist in the Jezero Crater, an ancient Martian riverbed, as pointed out by a recent discovery by NASA’s Perseverance rover. But the tale of these microbes’ friendship goes beyond this.

The bacterial duo forms a powerful partnership. Chroococcidiopsis releases oxygen, creating a microenvironment in which Sporosarcina pasteurii can thrive. Moreover, Chroococcidiopsis secretes extracellular polymeric substance that protects Sporosarcina pasteurii from harmful UV radiation on the Martian surface. In turn, Sporosarcina secretes natural polymers that nurture mineral growth and strengthen Martian regolith, turning loose soil into solid, concrete-like material. Being an oxygen producer, Chroococcidiopsis could also provide the life-support systems for astronauts. Over longer timescales, the ammonia produced as a metabolic by-product of Sporosarcina pasteurii might be harnessed to invent closed-loop agricultural systems and potentially aid terraforming of Mars.

As space agencies dream of sending humans to Mars by the 2040s, each such invention brings us closer to the prospect of building our home away from home on the Red Planet.

More on Starlust

10 Reasons Why Humanity May Want To Colonize And Live On Mars