Astronomers discover 'Cosmic Grapes,' a clumpy rotating galaxy formed 900 million years after Big Bang

A team of astronomers, with lead author Seiji Fujimoto from the University of Toronto, has recently published groundbreaking research on the earliest stages of galactic evolution. They have uncovered a remarkably clumpy, rotating galaxy that formed just 900 million years after the Big Bang, as mentioned by the McDonald Observatory.

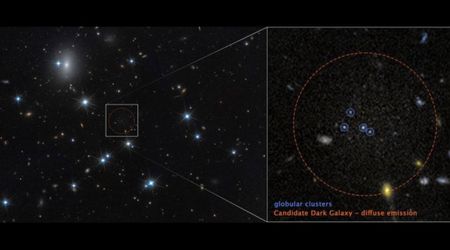

Nicknamed the "Cosmic Grapes," this galaxy stands out because of its unique structure. Rather than being a single, smooth disk as previously believed, observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have revealed it's composed of at least 15 distinct, massive star-forming clumps. This number far exceeds what current theoretical models predict could exist within a single rotating disk at this early time.

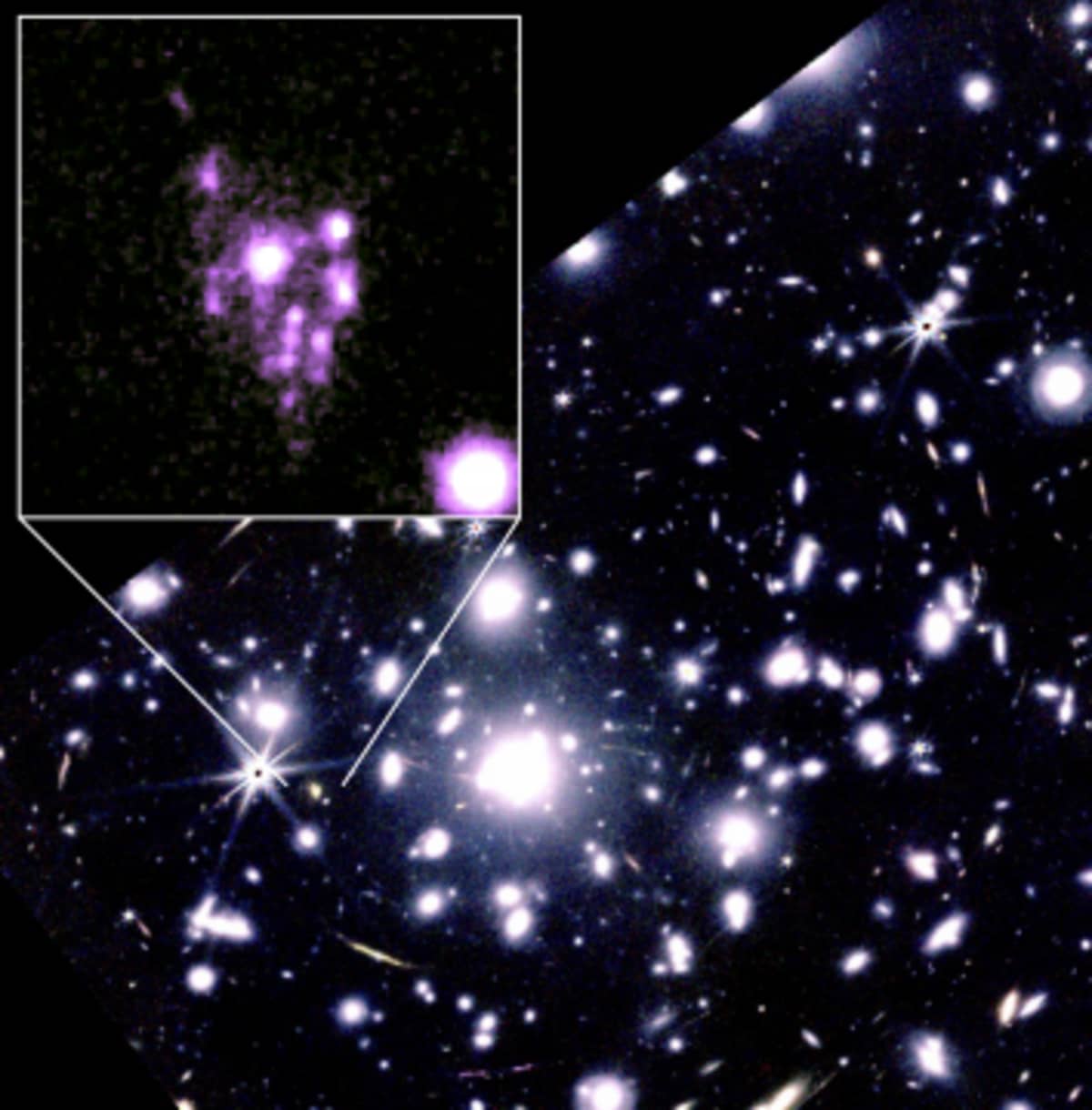

The discovery, detailed in a paper published in Nature Astronomy on August 7, was made possible by a rare cosmic alignment. The galaxy's light was perfectly magnified by a foreground galaxy cluster through a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. This natural magnification allowed astronomers to see the distant galaxy in striking detail. “Thanks to this powerful natural magnification, combined with observations from some of the world’s most advanced telescopes, we had a unique opportunity to study the internal structure of a distant galaxy at unprecedented sensitivity and resolution,” said Fujimoto, who began this work at the University of Texas at Austin and is now with the University of Toronto.

The finding challenges current theories on how galaxies form and evolve. Mike Boylan-Kolchin, a professor of astronomy at UT Austin and co-author on the paper, notes that the young starlight in these early galaxies is dominated by these dense clumps, rather than a smooth distribution of stars. The discovery suggests that our understanding of feedback processes and structure formation in young galaxies may need significant revision.

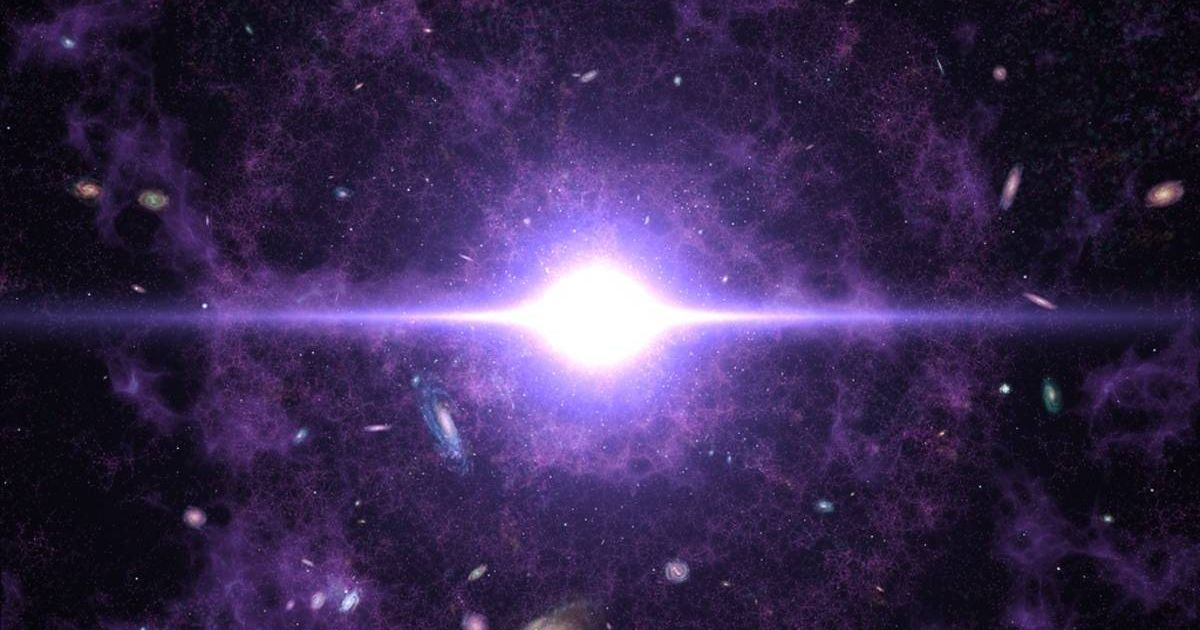

In a separate but equally monumental finding, an international team of astronomers has identified the oldest confirmed black hole in existence. The colossal object, located in the distant galaxy CAPERS-LRD-z9, existed just 500 million years after the Big Bang. This discovery, led by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin’s Cosmic Frontier Center, pushes the boundaries of what can be detected by current technology.

Texas Research Impact: @TexasScience researchers are pushing the boundaries of astronomy.

— UT Austin (@UTAustin) August 6, 2025

Using @ESA_Webb data, they’ve confirmed the earliest known black hole — offering new insight into how galaxies formed in the early universe.

🔗 https://t.co/4PYmwj9SBy pic.twitter.com/Iurhu9PVh3

This black hole is an incredible 13.3 billion years old, existing when the universe was only 3% of its current age. The team's findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal, provide the first definitive spectroscopic evidence of a black hole from this early period. Anthony Taylor, a postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study, highlighted the importance of this unique spectroscopic signature, which provides definitive proof of its existence and age, a feature that previous black hole candidates lacked.

According to Steven Finkelstein, a co-author of the paper and director of the Cosmic Frontier Center, this finding solves a long-standing mystery about the intense brightness of "Little Red Dots". The team's research suggests that instead of being fueled by a high number of stars, the galaxies' powerful light is generated by the tremendous heat and energy created as the black hole consumes surrounding material. This challenges previous assumptions about the brightness of these early galaxies and provides a unique window into the universe's infancy.