A Jupiter-family comet stuns scientists by abruptly reversing its spin after perihelion

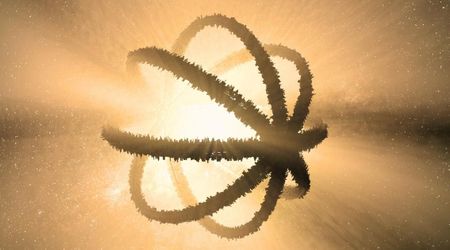

In 2017, comet 41P/Tuttle–Giacobini–Kresak, a modest Jupiter-family comet, did some acrobatics while zipping through the inner solar system. First, it slowed its rotation. Then, slowing further, it literally stopped. Now, a new analysis of archival observations from the Hubble Space Telescope reveals that this icy body, also called 41P/TGK, might have actually undergone full spin reversal after its closest approach to the Sun in April 2017. The analysis, done recently by David Jewitt, an astronomer at the University of California in Los Angeles, has been published in a paper on the arXiv preprint server.

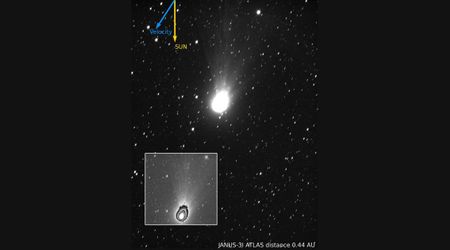

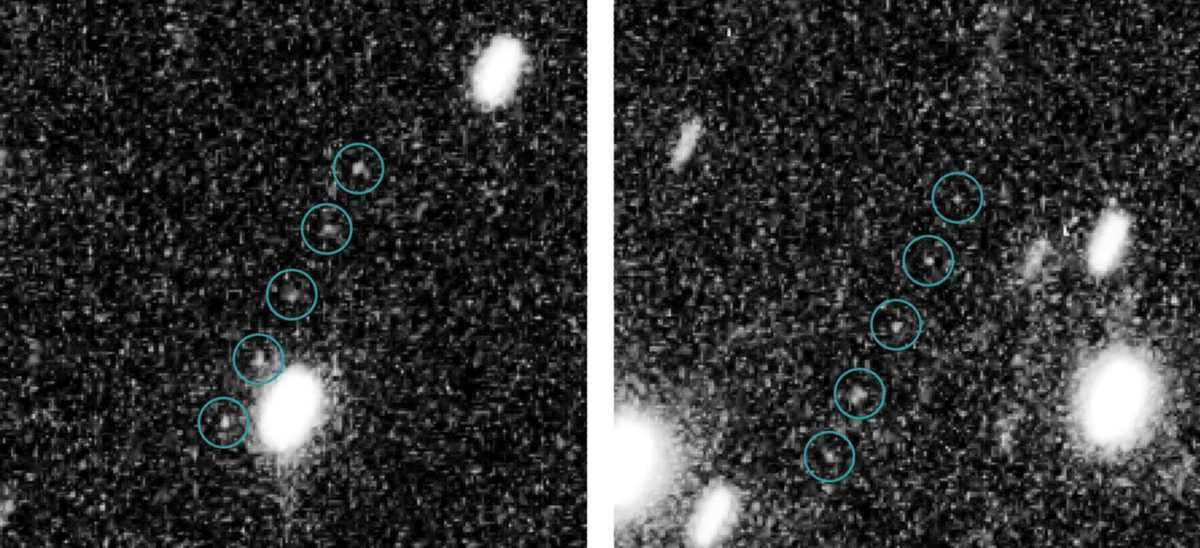

In April 2017, the comet reached its closest position to the Sun, which heated the comet’s nucleus, turning its frozen volatiles directly into gas, a process known as outgassing. "Remarkable observations from 2017 show a rapid increase of the rotation period of the nucleus, deduced both photometrically and from rotating jets. The period more than doubled, from P ∼20 hours to ∼53 hours, over the course of two months near perihelion,” Jewitt explains in the study. "The simplest explanation of the changing period is that the nucleus was torqued by recoil forces from anisotropic outgassing, as has been widely demonstrated in other comets." However, lack of data during post-perihelion prevented scientists from deciphering what really happened to this comet that likely originated in the Kuiper Belt, the doughnut-shaped region of icy bodies far beyond the orbit of Neptune. After perihelion, the comet vanished from view and then reappeared in December 2017 when Hubble captured its images again. Using these and other images, Jewitt did photometry to measure the comet’s nucleus size and probed the light curve to determine its rotation period. He found that the comet has a small nucleus with an effective radius of around 500 meters.

The most intriguing finding of the analysis was the evidence that the comet had changed its direction of spin in the period between the April and December observations. The rotation period of the comet had dropped drastically to 14.4 hours, which was much shorter than what had been noted earlier. This indicated that the comet's rotational speed had gone up. Jewitt explains that the comet must have slowed down to the point that it came to a complete halt around June 2017 before beginning to spin again, this time in the opposite direction, increasing its rotational speed in the process.

"Rotational changes in TGK, although dramatic by the standards of most other cometary nuclei, are a simple consequence of its small size, not of outgassing that is unusual in magnitude or angular pattern," Jewitt writes. He also predicts that the rapidly changing rotation of the comet may lead to its rotational breakup in around 25 years. 41P/TGK is likely going to reach perihelion in another two years' time, giving astronomers a shot at getting some additional insights.

More on Starlust

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS tracked again by NASA’s exoplanet hunter TESS

Comet C/2026 A1 (MAPS) is plunging directly toward the Sun—current location and trajectory