Solar wind from giant coronal hole expected to hit Earth just before 3I/ATLAS' closest approach

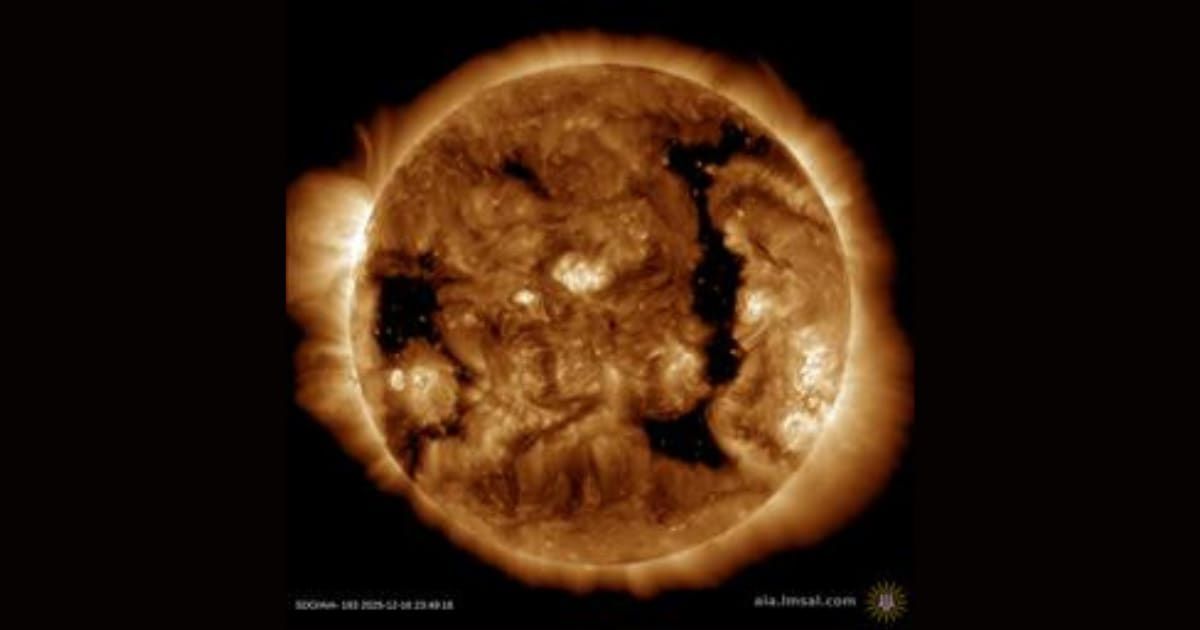

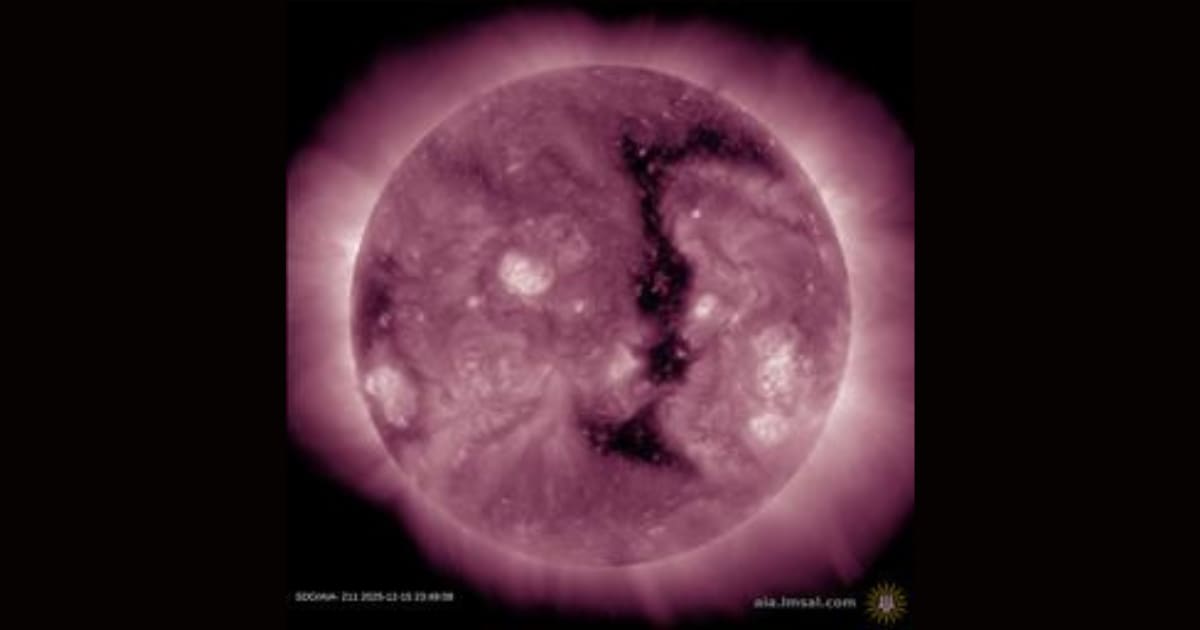

Forecasters have issued alerts for potential geomagnetic storms due to solar material hurtling toward Earth. Two coronal mass ejections—giant bursts of solar wind—were spotted on December 16 and are now racing toward our planet, according to the Space Weather Prediction Center.

The CMEs will arrive just before the close approach of Comet 3I/ATLAS, which will happen this Friday, December 19, 2025. Crucially, the comet poses no threat whatsoever to our planet, passing by at a distance of 167 million miles (1.798402 Astronomical Units), according to Sky Live. This separation is almost twice the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

The first CME should arrive late in the day on December 18, Thursday, and is forecast to produce a G1 (minor) geomagnetic storm. The second and stronger CME arrives a little later, early on December 19. That one is predicted to raise the activity to a G2 (moderate) storm level, says the Space Weather Prediction Center.

The geomagnetic disturbance may persist for some time due to the unending stream of fast solar wind; Kp could reach 5. According to Earth Sky, if this indeed happens, observers in high-latitude regions, cities like Reykjavik, and areas of northern Scotland and southern coastal Alaska may witness a short-term yet dramatic intensification of the Northern Lights, or aurora borealis, visual evidence of "space weather," a dynamic cosmic interaction involving the Sun and Earth. These colorful, often delicate light shows are visual evidence of the intricate dance between charged particles and magnetism, according to NASA.

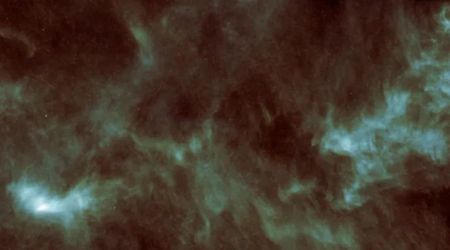

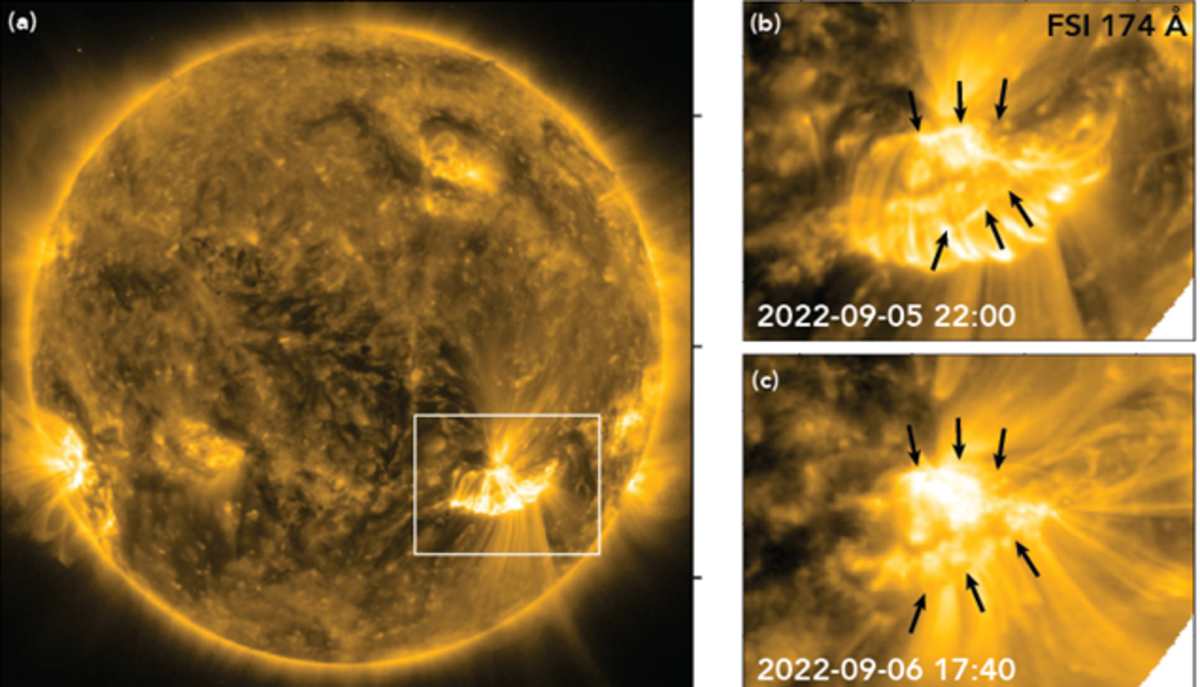

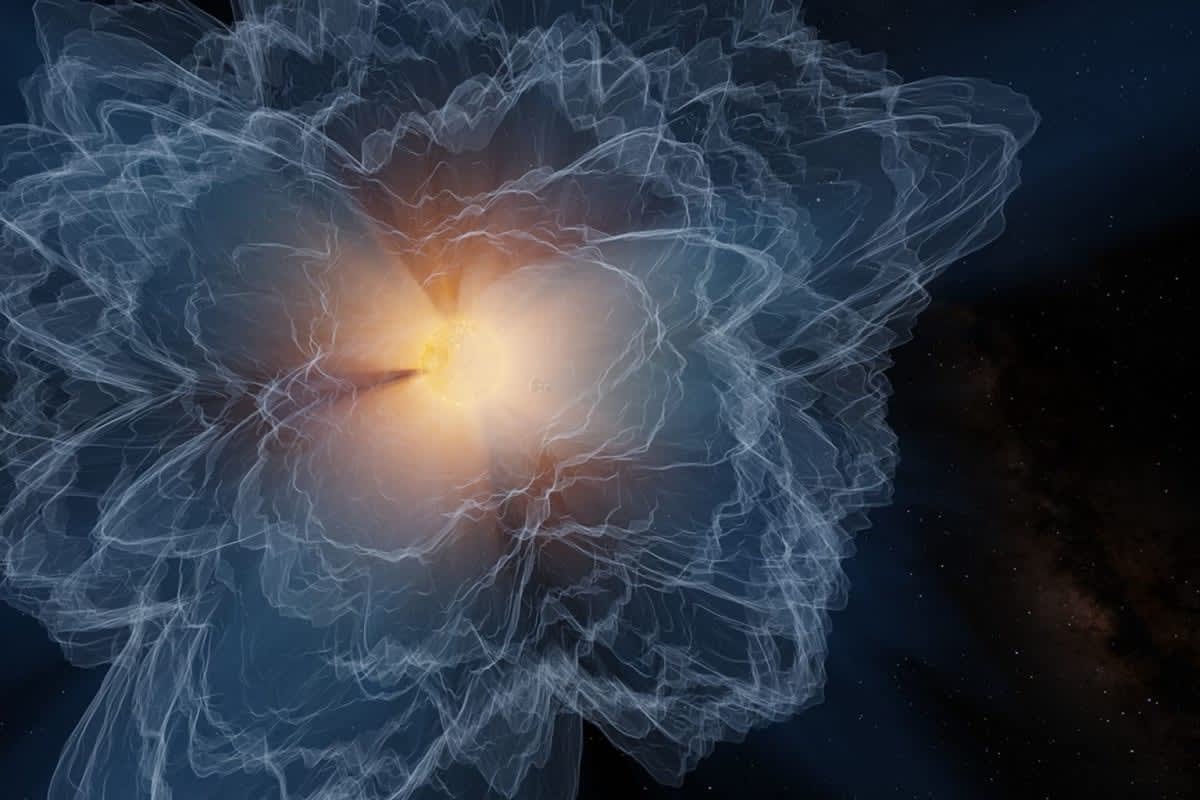

Meanwhile, in a major solar science achievement, astronomers using NASA's Parker Solar Probe have created the first continuous, 2D maps of the outer limit of the Sun's atmosphere, per NASA. This critical boundary, which researchers call the Alfvén surface, is the point where the Sun's material finally breaks free to form the solar wind, the super-fast, million-mile-per-hour stream of charged particles that permeates the solar system, affecting everything from planets to spacecraft. The new findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, rely on data from the probe's SWEAP instrument. The maps show that as the Sun progresses through its natural 11-year cycle and becomes more active, this escape boundary grows larger, becomes rougher, and develops spikier features.

While others, the Solar Orbiter and NASA's Wind, have been tracking this boundary, the Parker Solar Probe is uniquely positioned: flying closer to the Sun than any mission before it, it repeatedly crosses the Alfvén surface. This unprecedented proximity provides direct confirmation of those maps and shows precisely how the boundary shifts with solar activity. Pinpointing the exact position and nature of this boundary is crucial. This could hold the key to unraveling some of the longest-standing mysteries about the Sun's superheated outer layer, or corona, and improve our understanding of how solar activity affects technology and life throughout the solar system, including here on Earth.

More on Starlust

Triple coronal mass ejections are headed to Earth and could trigger auroras in northern skies

Dual solar wind streams from two giant coronal holes could reach Earth on October 3