Groundbreaking supercomputer simulations explain why black holes are so bright

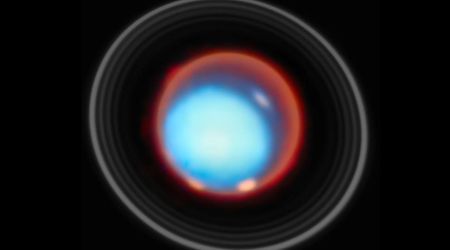

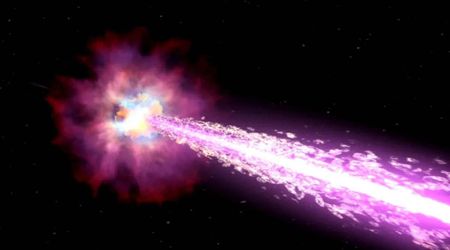

Despite what their names might suggest, black holes are some of the brightest objects in the universe. The glow comes from the gas and dust that flow around and into a blackhole. The most comprehensive simulation of how this happens has now been developed by a team of computational astrophysists. To figure out the behavior of the material present around black holes, the researchers used a full treatment of how light moves and interacts with matter within Albert Einstein's general relativity.

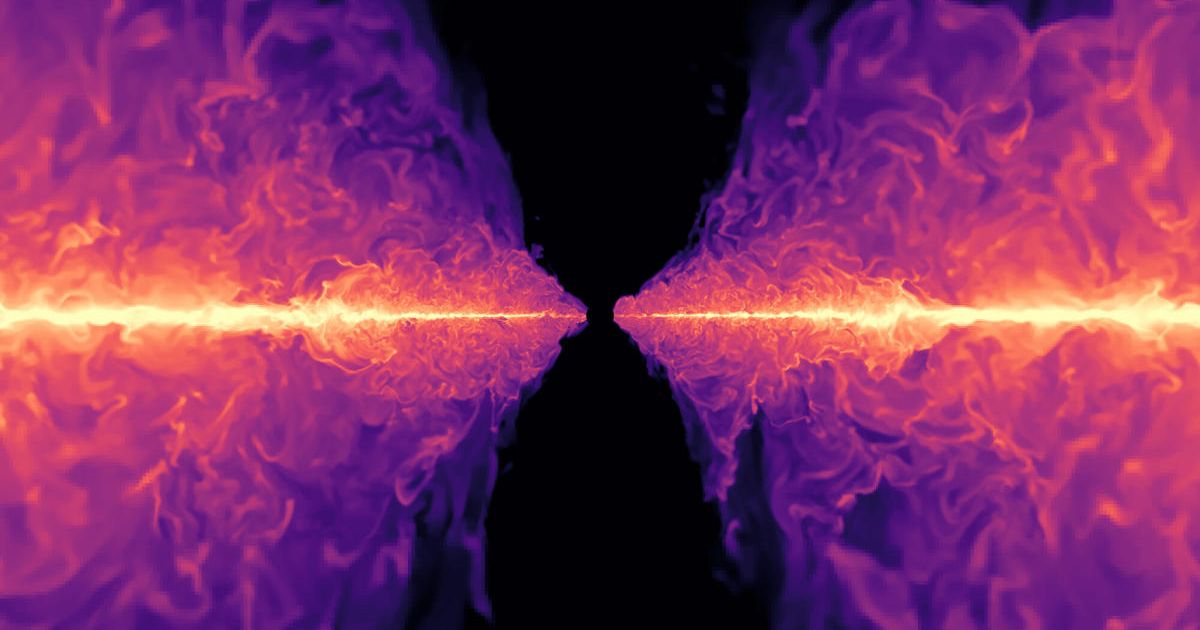

Incorporating Einstein's theory of general relativity was a non-negotiable, as a model of black holes would be incomplete without it. After all, the theory describes how the massive bodies distort space-time, which, in turn, influences how light created by the material falling in interacts with the surrounding material. "Previous methods used approximations that treat radiation as a sort of fluid, which does not reflect its actual behavior," explained lead author Lizhong Zhang, per Phys.org. Zhang, who is also a research fellow at the Simons Foundation's Flatiron Institute in New York City, then warned that oversimplifying assumptions can distort outcomes, before noting how the simulations produced by his team can replicate the behavior of black holes seen in the sky with remarkable consistency. "In a sense, we've managed to 'observe' these systems not through a telescope, but through a computer."

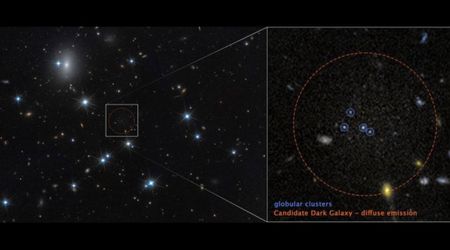

The results, published on December 3 in the Astrophysical Journal, could offer an explanation for little red dots (LRDs)—faintly luminous objects that the James Webb Space Telescope observed in the early universe. Their paper supports a leading theory that suggests that these objects are black holes that are feeding on material through a process referred to as 'super-Eddington accretion' in the middle of galaxies as old as time.

The simulation is going to be crucial for the study of stellar mass black holes as well. While supermassive black holes have been captured in high-resolution images, stellar mass ones cannot be observed that way, as they appear as pinpoints of light. So to chart how energy is distributed around these structures, scientists resort to converting light into a spectrum. Zhang and his team found that their simulation was in agreement with the spectrum provided by observational data—something that is crucial for making a better interpretation of the limited data that stellar mass black holes come with.

The simulations in question were based on an algorithm developed by Yan-Fei Jiang of the CCA. It blends an angle-sensitive method for following how radiation moves and interacts with matter with a fluid-flow model describing motion around a spinning sphere under a powerful magnetic field.

The team responsible for the simulations will work to test if their model applies to all types of blackholes. Apart from helping understand stellar mass black holes, the simulations could also help study supermassive black holes, which are the driving force behind the evolution of galaxies. Part of the team's efforts will be aimed at accounting for the various ways in which radiation and matter interact across temperatures and densities.