Dual-temperature plasma eruptions from sun-like star rewrite understanding of early Earth conditions

An international research team has achieved a pivotal breakthrough in stellar astrophysics, successfully capturing a detailed picture of the powerful plasma eruptions from a young, Sun-like star, according to the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ).

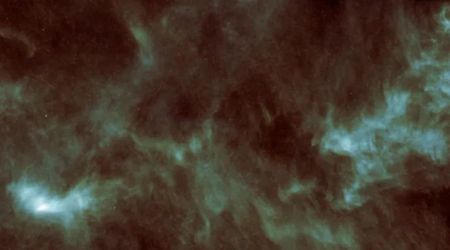

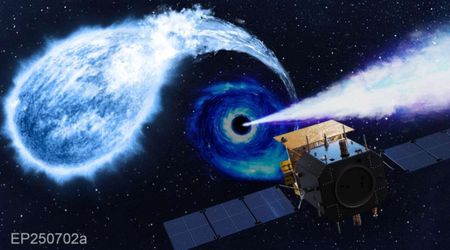

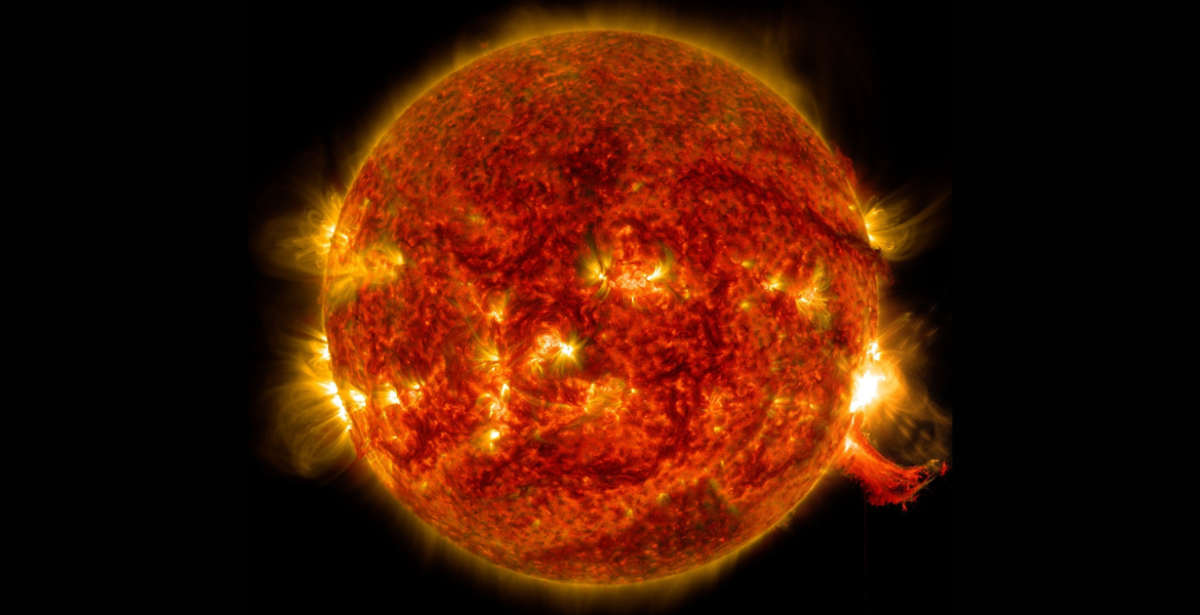

The unprecedented observations reveal that these stellar outbursts, which mimic the Sun's own Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), are composed of a two-speed, two-temperature blast, a finding that significantly impacts our understanding of conditions on early planets, including Earth. The study, led by Kosuke Namekata of Kyoto University, focused on EK Draconis, a stellar neighbor located 111 light-years away in the Draco constellation. Utilizing a coordinated campaign that combined Hubble Space Telescope's ultraviolet (UV) capabilities with simultaneous optical data from ground-based telescopes in Japan and Korea, astronomers were able to measure different plasma components of a single CME, a feat previously unattainable.

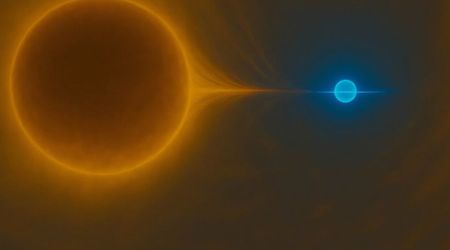

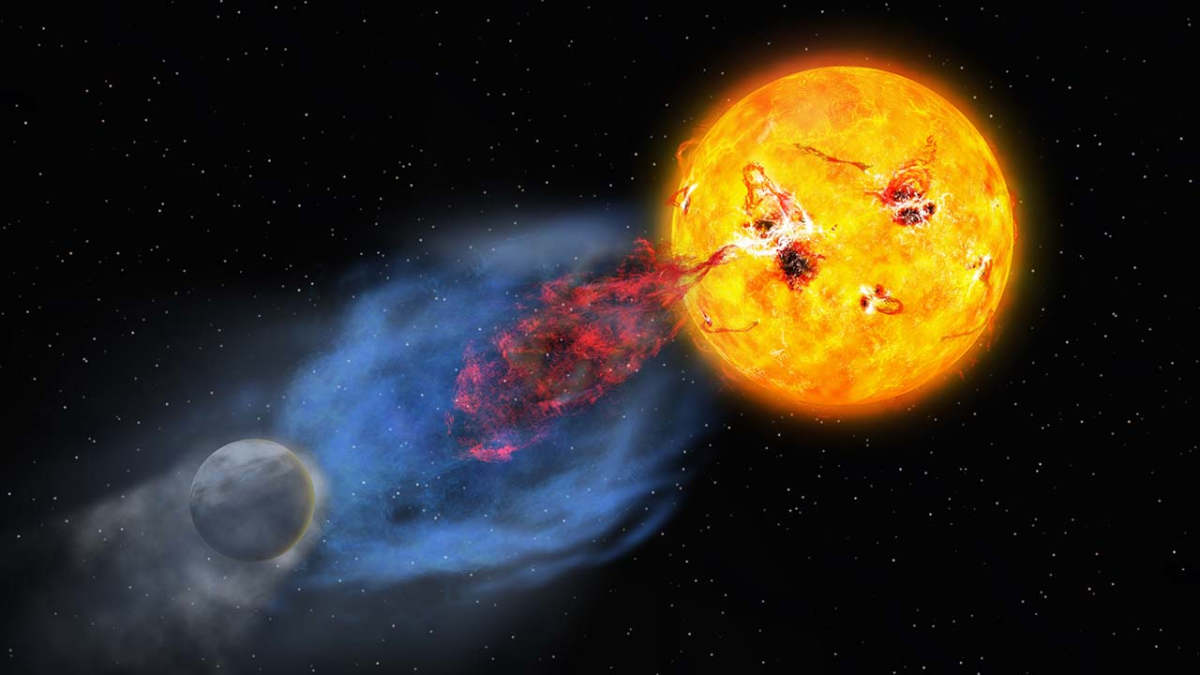

The synchronized observations confirmed that the star's eruption was not a uniform expulsion. Instead, it was a dramatic dual-stage event. A superheated component, measured at 100,000 Kelvin, was ejected first at extreme speeds ranging from 300 to 550 kilometers per second. This was followed approximately ten minutes later by a substantially cooler gas component, measured at about 10,000 Kelvin, which moved at a much slower speed of 70 kilometers per second. This discovery indicates that the hotter plasma possesses significantly higher kinetic energy than its cooler counterpart. Scientists had previously been limited to measuring only the cooler, less energetic plasma in stellar CMEs, leading to potential underestimates of their overall impact.

Modern stellar CMEs on our own Sun are known to contain various temperature components, but young, active stars are known to produce flares and CMEs that dwarf anything seen from the modern Sun. Since the young Sun is presumed to have behaved much like EK Draconis, this new data suggests that the early Solar System was frequently bombarded by far more powerful and faster plasma ejections than previously theorized.

Science Release: Young Star Cooks Surroundings with Different Temperatures

— NAOJ (@prcnaoj_en) October 28, 2025

Astronomers have used simultaneous ground-based and space-based observations to measure the temperature and velocity of gas ejected from a young Sun-like star. https://t.co/Xq70TosEPQ pic.twitter.com/HY2Xvv1dJF

Fast, energetic CMEs are considered a double-edged sword: while they pose a threat to planetary atmospheres, theoretical and experimental evidence suggests they might also play a role in synthesizing essential biomolecules and forming greenhouse gases, processes crucial for the initiation and maintenance of life. The research, therefore, has major implications for modeling planetary habitability and the environmental conditions that gave rise to life on Earth. The team plans to extend their research using X-ray and radio observations, underscoring the vital role of UV astronomy and future missions like JAXA’s LAPYUTA in unlocking the secrets of planet formation.

The research team credits the breakthrough to the success of international cooperation and the meticulous, synchronized operation of both space- and ground-based facilities, per Kyoto University. The ability to coordinate observations between the orbiting Hubble Space Telescope and optical instruments in Japan and Korea was fundamental to capturing the crucial, multi-component CME data.

"We were happy to see that, although our countries differ, we share the same goal of seeking truth through science," stated Namekata, emphasizing the collaborative spirit that drove the ambitious project.