Controlled experiment allowed viruses to attack bacteria in space—and the results surprised scientists

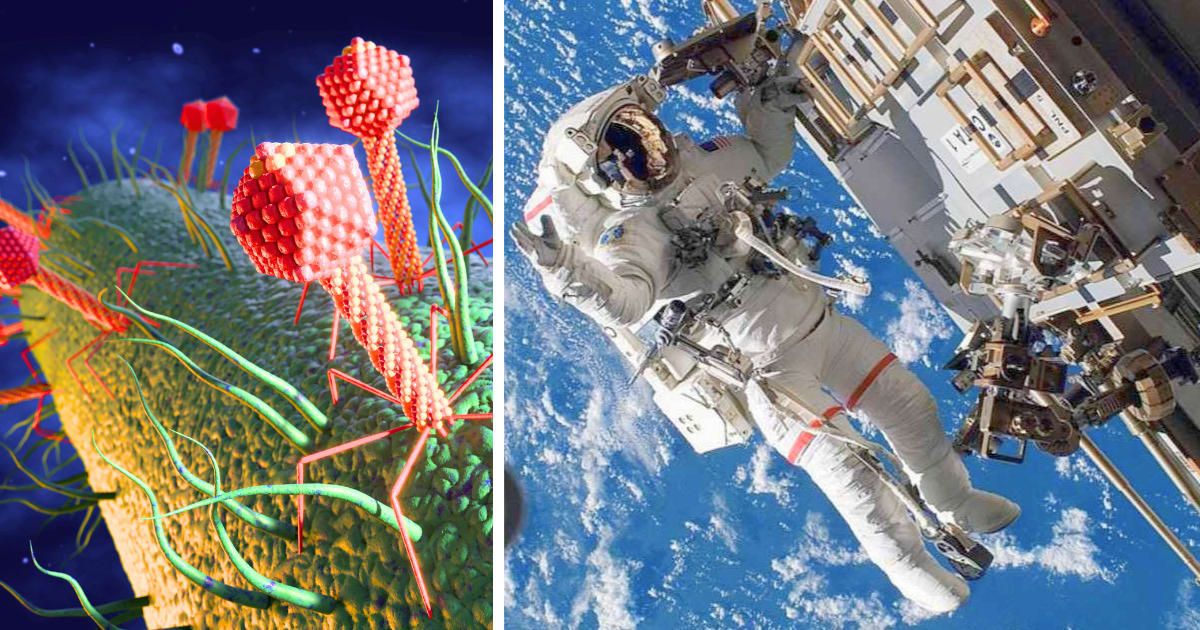

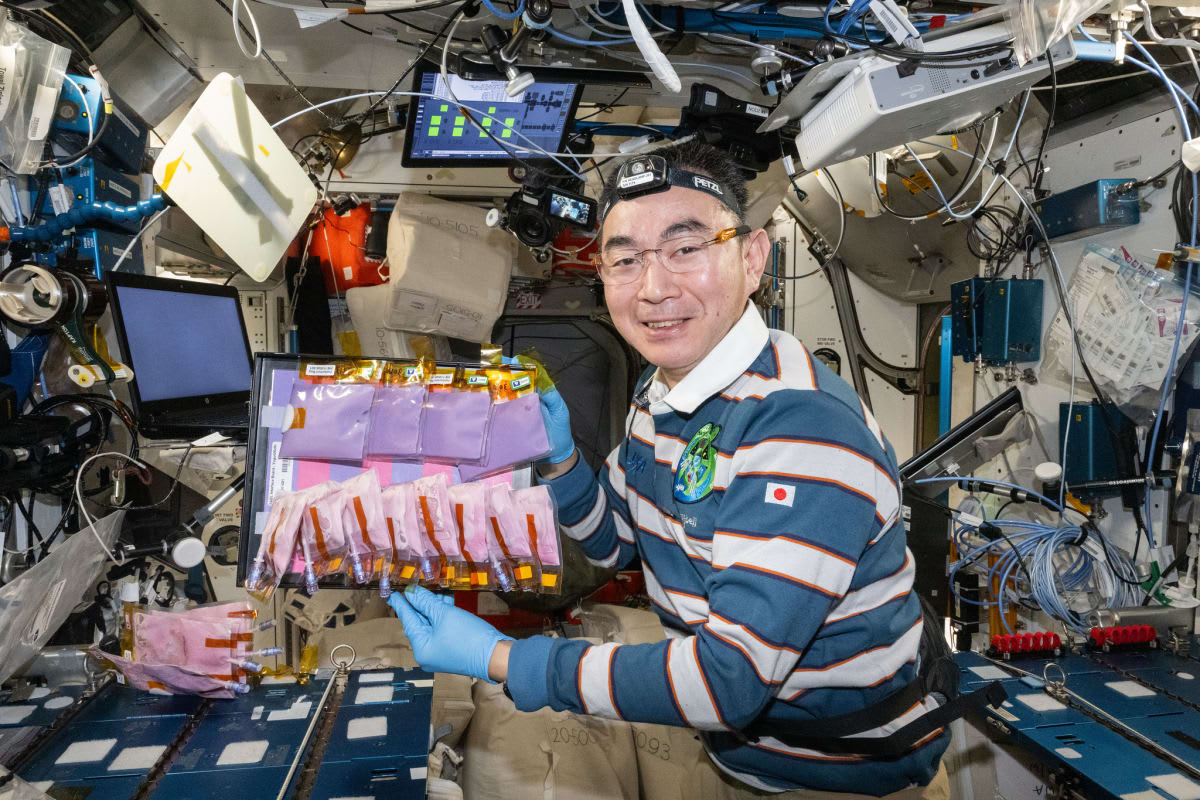

The International Space Station (ISS) hovers 250 miles above us, orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour. So far, it has welcomed nearly 300 astronauts. And now, this remote outpost also receives microbial guests from Earth. In a recent study titled 'Microgravity reshapes bacteriophage–host coevolution aboard the International Space Station,' published in the journal PLOS Biology on January 13, 2026, bacteria-infecting viruses were made to interact with their E. coli hosts on the space station. The aim was to probe how microgravity shapes the viruses and their abilities to infect and devour the bacteria.

After analyzing the space station’s samples on Earth, a research team led by Phil Huss at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has found that phages, which are bacteria-infecting viruses, were able to infect the target, but the interactions differed from those observed on Earth. Phages are eternally locked in an "arms race" with bacteria, according to EurekAlert. The viruses devise ploys to break into bacterial defenses. Bacteria, on the other hand, strengthen their defenses so that they can easily thwart viral attacks. To find out how microgravity influences these battles, the team incubated one set of the phage known as T7 and E. coli on Earth and compared it with another set grown on the ISS.

Analysis of the space station samples showed that the phage initially held back, but gradually invaded the bacterial cells. Sequencing their genomes revealed distinct changes in the genetic mutations in bacteria and viruses between the Earth samples and the microgravity samples. The space station viruses acquired specific mutations that could enhance their ability to latch onto bacterial cells. Meanwhile, the bacteria grown on the space station accumulated mutations that could protect them against the viruses.

Further differences between Earth-grown and space-grown samples were revealed when the researchers carried out a deep mutational scan to make better sense of the changes in the binding protein that helps T7 latch on to bacteria. Follow-up investigations on Earth showed that the microgravity-induced changes in the binding protein are linked to heightened activity against urinary tract infection-causing E. coli strains that are typically unaffected by T7.

“Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth," the authors were quoted as saying by EurekAlert. They added, "By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth.” This research reveals new insights into microbial adaptation that can be exploited to benefit space exploration and human health. It turns out that the arms race between phages and bacteria that began eons ago on Earth rages on even in the near-weightlessness of the space station.

More on Starlust

Astrophotographer catches the International Space Station in lunar transit