Astronomers spot supernovas whose split light could tell us how fast the universe is expanding

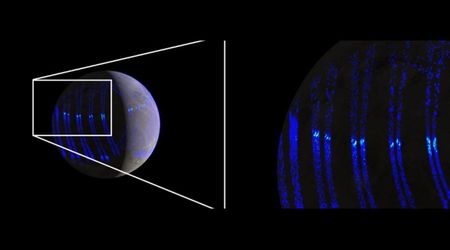

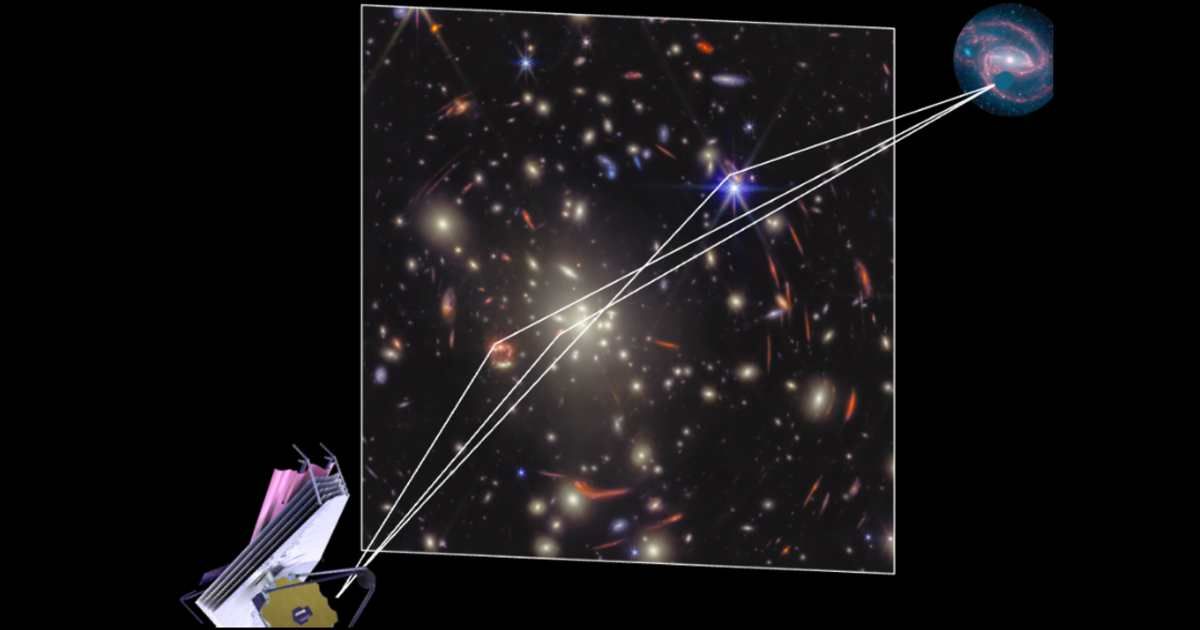

The universe is expanding. But how fast? SN Ares and SN Athena, two distant supernovas that exploded billions of years ago, may provide the answer, according to astronomers from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and the JWST Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources (Venus). Before reaching Earth, light from the supernovas was bent by gravitational lensing, which created multiple images of the dead stars, each of which will take a different path through space-time toward Earth. These supernova observations are among the first results from the VENUS treasury program. The VENUS survey uses the James Webb Space Telescope, which scans the sky and zooms in on 60 galaxy clusters and waits to capture such gravitationally lensed images of distant exploding stars. Comparing the images, researchers will be able to tell the expansion rate of the universe.

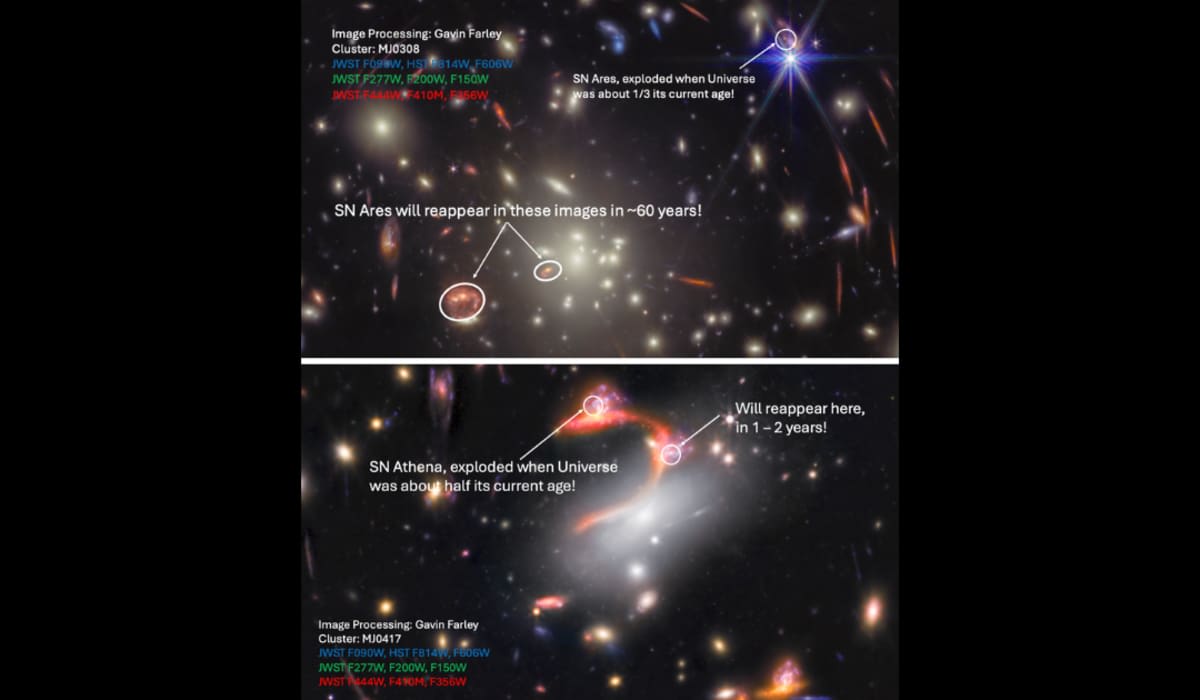

Presented at a news conference at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, the findings reveal that there is a time gap between images. SN Ares, the first supernova that the astronomers observed, exploded nearly 10 billion years ago and had its light split into three images by a galaxy cluster designated MJ0308. While one image has already arrived, the researchers predict that the other two will take another 60 years to get here. The delayed image of SN Athena, which came into existence when the universe was half its current age, on the other hand, will appear in about 1 to 2 years. "Strong gravitational lensing transforms galaxy clusters into nature's most powerful telescopes," Seiji Fujimoto, principal investigator of the VENUS program and an astrophysicist at the University of Toronto, said in a statement. "VENUS was designed to maximally find the rarest events in the distant Universe, and these lensed [supernovas] are exactly the kind of phenomena that only this approach can reveal."

"Such a long-anticipated delay between images of a strongly lensed supernova has never been seen before and could be the chance for a predictive experiment that could put unbelievably precise constraints on cosmological evolution," said Conor Larison, a postdoctoral research fellow at STScI. The images from the supernovas will also help establish better constraints on the Hubble Constant, which denotes the rate of the universe’s expansion. Currently, it shows two different values. One value, based on the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation—the oldest light in the universe, emitted when the cosmos was only 380,000 years old—yields a universal expansion rate of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. The other, calculated using "standard candles" like Cepheid stars, a type of star used to measure distances in space by how they change brightness, yields a value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

"Since VENUS started last July, we have discovered 8 new lensed supernovae over 43 observations, almost doubling the known sample in a remarkably fast time frame," Larison told LiveScience.com. "It seems that, although lensed supernovae are certainly rare, the real limitation has been in observing capabilities. It is really only with JWST that we are achieving the depth and wavelength coverage necessary to find these en masse, which is exactly what VENUS was designed to do." Lensed supernovas are very important to study how the universe has evolved and measure its rate of expansion since it was born around 13.8 billion years ago.

More on Starlust

Astronomers using JWST discover an ancient supernova from the first billion years of the universe