Astronomers discover smallest dark matter clump ever — yet it has a mass a million times greater than our sun's

An international astronomy team has pinpointed what may be the smallest pure concentration of dark matter ever detected, a crucial finding that strongly supports standard theories of galaxy formation, as per Universe Today.

Mysteriöses dunkles Objekt im All: Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler vom Max-Planck-Institut für #Astrophysik haben das bislang kleinste gemessene dunkle Objekt mithilfe seines Gravitationseffektes nachgewiesen. https://t.co/mRJ1A7TB4I pic.twitter.com/tf3Ck08vJf

— Max Planck Society (@maxplanckpress) October 9, 2025

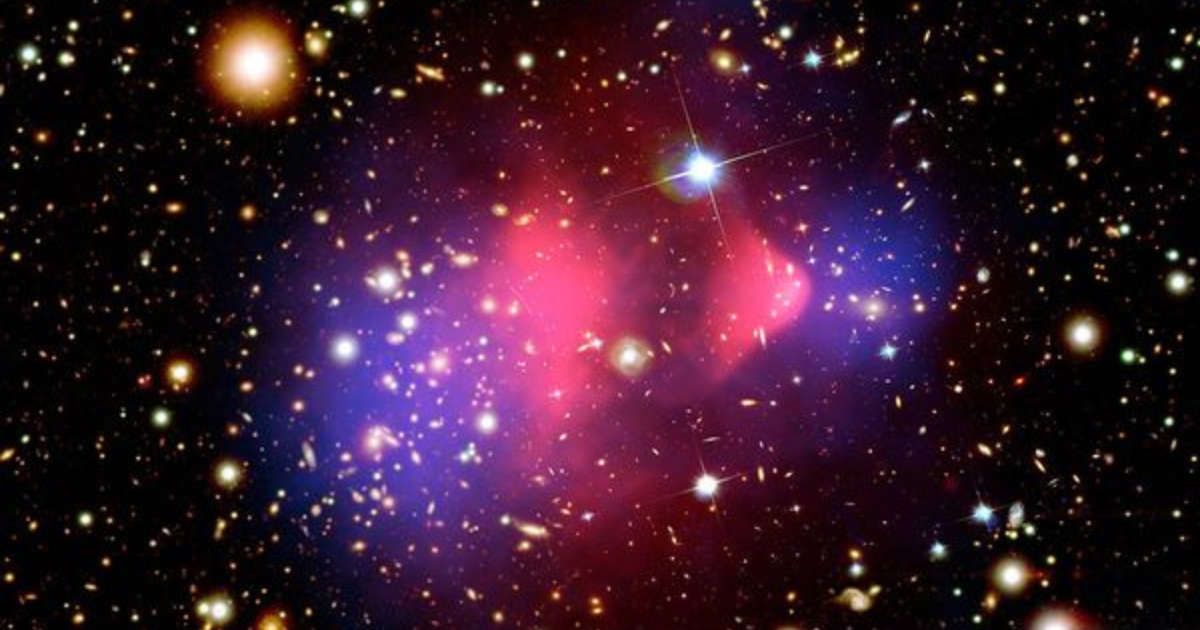

The invisible, enigmatic substance known as dark matter constitutes roughly 85% of the universe’s total matter but remains undetectable by conventional means, as it does not interact with light. Its existence is inferred solely through its powerful gravitational effects on visible cosmic structures like galaxies and galaxy clusters. A collaborative team, led by Dr. Devon Powell of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, successfully isolated a minuscule dark matter clump, weighing approximately one million times the mass of our Sun. This object is located a staggering 10 billion light-years from Earth, providing a glimpse into the universe when it was only 6.5 billion years old.

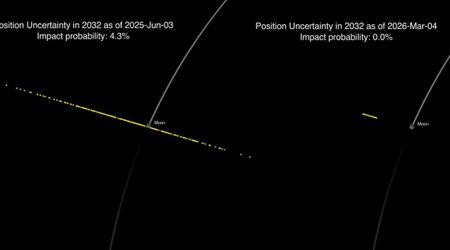

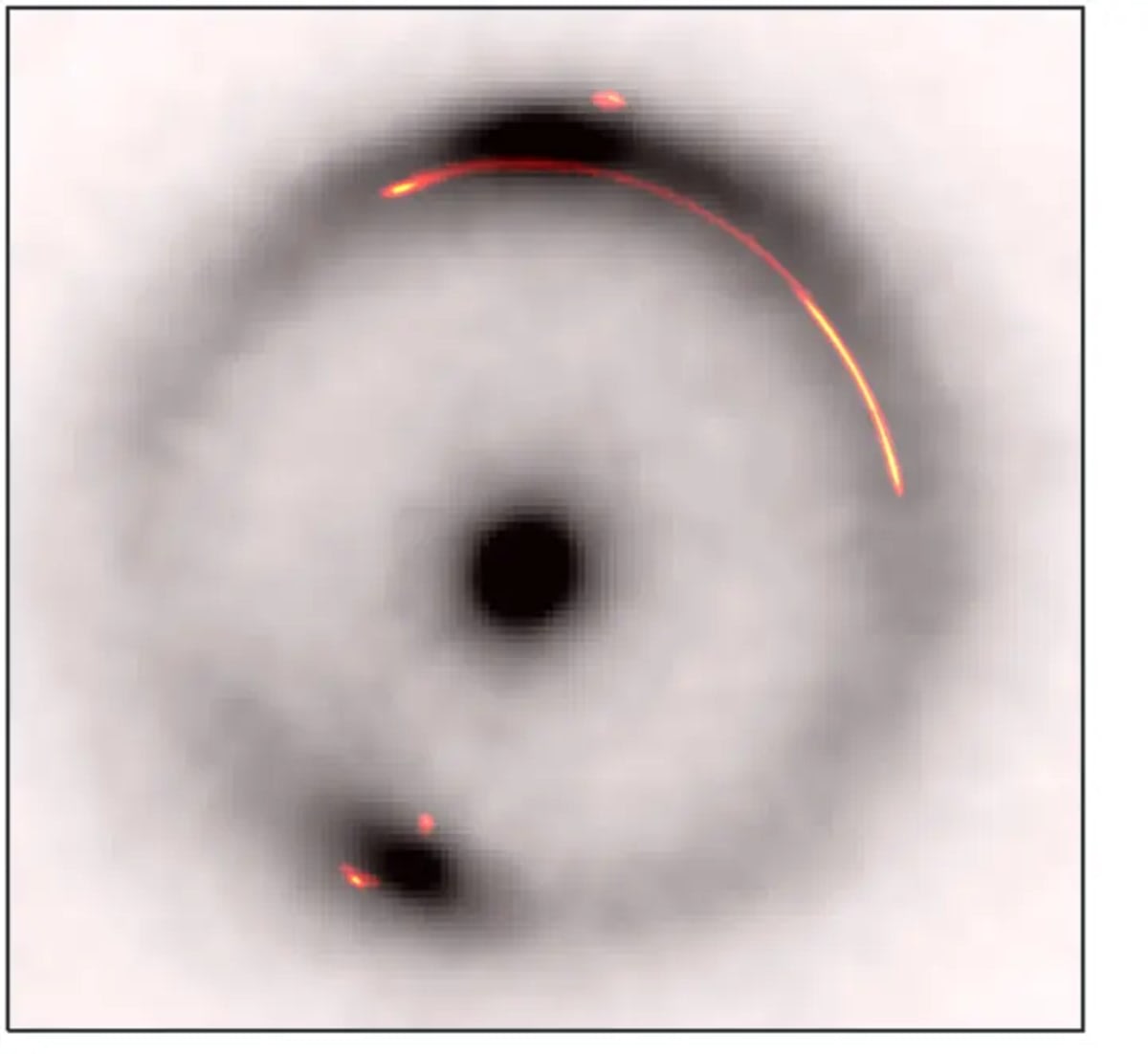

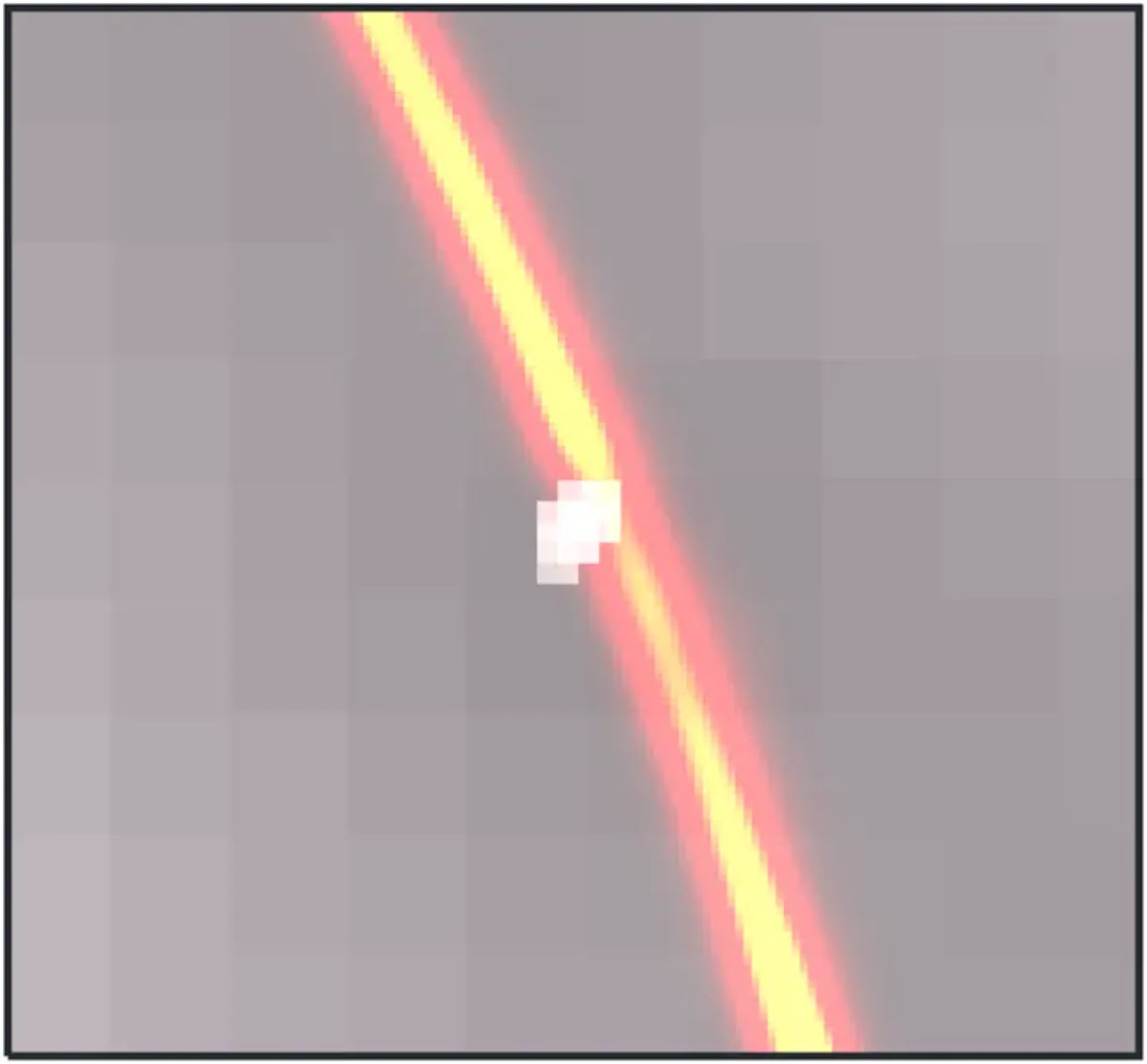

The discovery was facilitated by coordinating radio observatories across continents, from the United States to Europe, to create a virtual, Earth-sized telescope. The researchers leveraged gravitational lensing, a phenomenon predicted by Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, where a massive foreground object warps spacetime, bending the light of objects behind it. While observing a system designated B1938+666, the team identified a subtle "pinch" or distortion within the gravitational arc known as an Einstein ring. This minute deformation could only be attributed to a previously unseen concentration of mass, the dark matter clump, situated between the observatories and the background galaxy.

As Dr. Powell detailed in the journal Nature Astronomy, the methodology involved using distant galaxies as "backlights" to find the invisible mass through its gravitational "fingerprint." Analyzing the immense data requires developing new computational methods and running them on supercomputers. The team effectively photographed the invisible object using a technique termed "gravitational imaging."

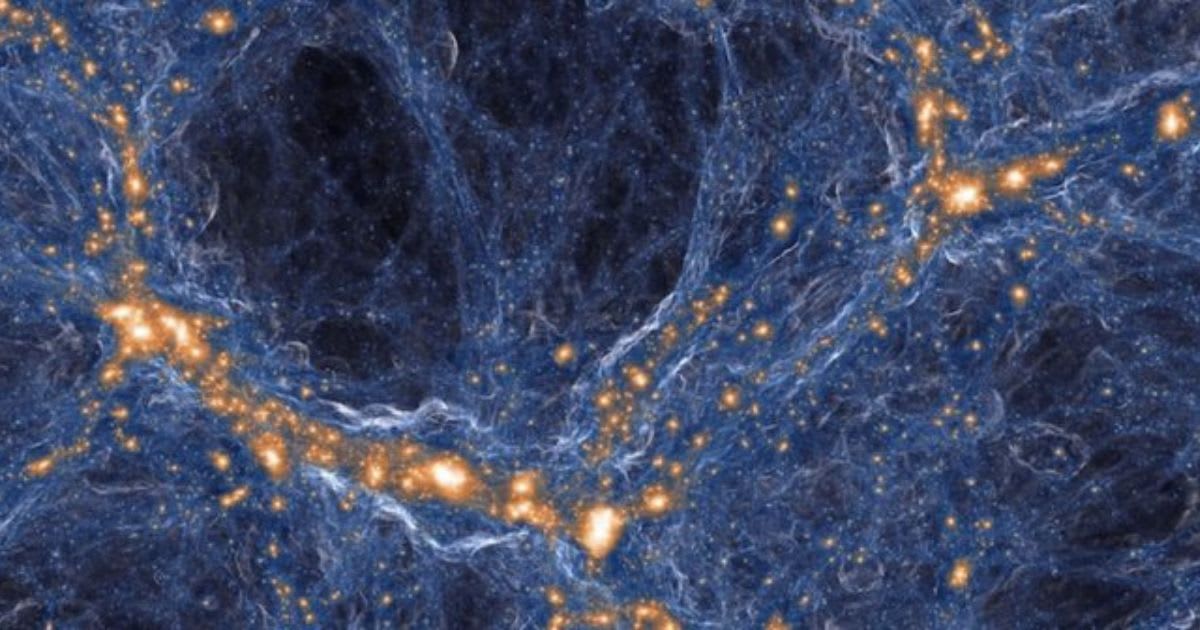

Crucially, the identification of this tiny dark concentration provides significant validation for the prevailing cold dark matter (CDM) theory of galaxy formation. This theory posits that dark matter is composed of slow-moving particles that began clumping together via gravity in the early universe, forming small structures that eventually merged into the larger galaxies and clusters observed today. The detection of such a small clump supports the prediction that dark matter is not smoothly distributed but aggregates into discrete, hierarchical structures.

Scientists expect similar dark matter clumps to be ubiquitous, filling the halos of all galaxies, including our own Milky Way. The next phase of research will focus on locating more of these structures to determine if their observed numbers continue to align with theoretical models. Future discrepancies could necessitate revisions to current theories on dark matter's fundamental nature.

The international search for smaller dark matter structures is set to receive a significant boost from NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to begin operations in 2027. The telescope is specifically designed to utilize the same technique of gravitational lensing, the distortion of light by massive cosmic objects, a phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, that led to the recent discovery. By precisely measuring how mass warps the fabric of time and space, Roman will provide critical new data, allowing astronomers to investigate the enduring mystery of dark matter's distribution and fundamental properties on an unprecedented scale.

More on Starlust

Black hole shadows could finally help detect the universe’s 'invisible' dark matter, say scientists

Black hole shadows could finally help detect the universe’s 'invisible' dark matter, say scientists