3I/ATLAS reveals first-ever ultraviolet clue to water in an interstellar comet in historic discovery

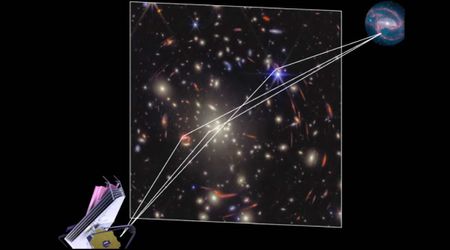

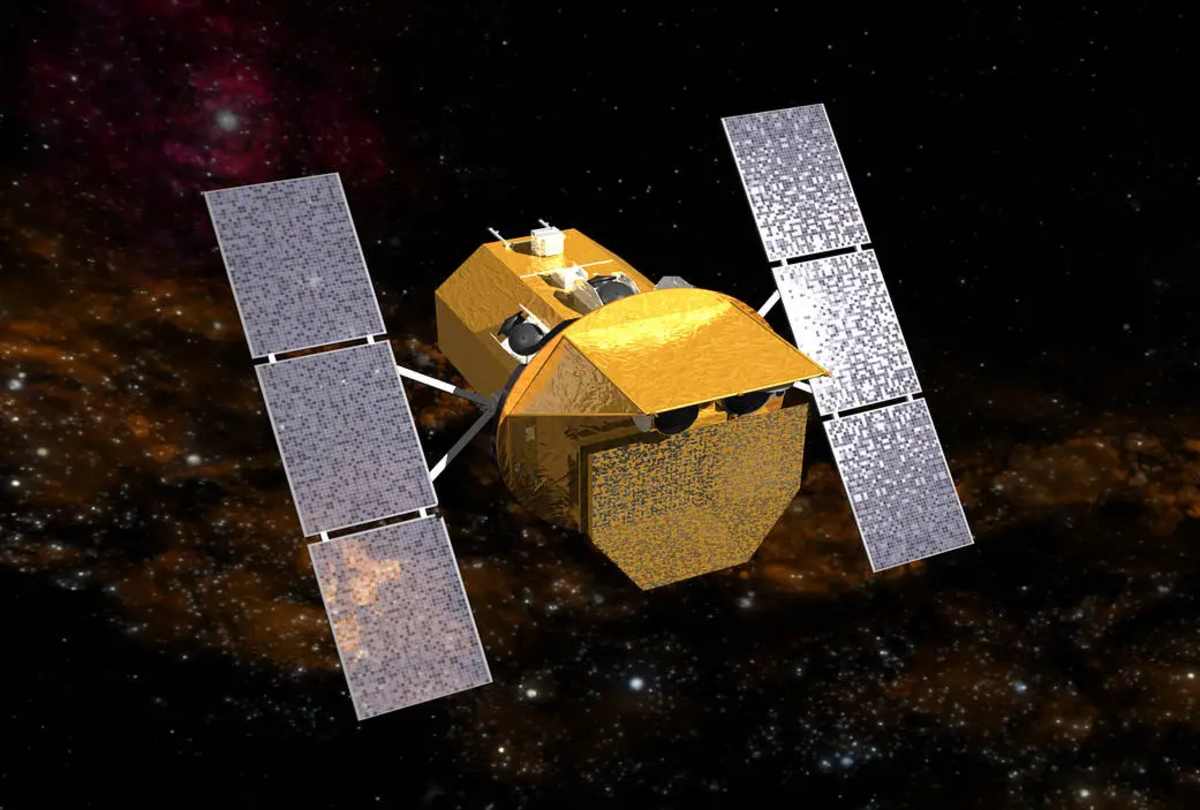

Astronomers have successfully detected the distinct ultraviolet signature of water in 3I/ATLAS, only the third interstellar comet ever observed, according to a new study from Auburn University scientists. The groundbreaking discovery, made using NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, provides the first opportunity to directly compare the volatile ice content of a visitor from deep space with comets native to our own solar system, reported Phys.org.

The Swift Observatory's space-based telescope captured the faint ultraviolet emission of hydroxyl (OH) gas, a key byproduct of water (H2O) breakdown. Crucially, this type of ultraviolet light is blocked by Earth's atmosphere, making the detection impossible for ground-based facilities. The detection of water's "chemical benchmark" in 3I/ATLAS is a significant step, allowing the study's co-authors Zexi Xing, Shawn Oset, John Noonan, and Dennis Bodewits to apply the same metrics used to gauge the overall activity and evolution of solar system comets. This moves scientists closer to comparing the planetary chemistry of star systems across the galaxy.

What makes the finding particularly remarkable is where the water was found. The Swift observations logged the OH emission when the comet was nearly three times farther from the Sun than Earth. At this distance, the solar heat is typically too weak for water ice on a comet’s surface to easily vaporize, leaving most solar system comets relatively dormant. Despite its distant location, 3I/ATLAS was found to be losing water at a prodigious rate: approximately 40 kilograms per second, an output comparable to a powerful fire hose.

This strong signal suggests a more complex mechanism is at play, possibly involving sunlight heating and vaporizing small, icy grains released from the nucleus. Such "extended sources" of water are rare and indicate the presence of deep, layered ices that preserve clues about the comet's formation. The increasing number of interstellar travelers is beginning to paint a varied picture of planetary building blocks across the cosmos.

"When we detect water—or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH—from an interstellar comet, we're reading a note from another planetary system," said Dennis Bodewits, a professor of physics at Auburn. "It tells us that the ingredients for life's chemistry are not unique to our own." The three known interstellar objects have shown dramatic chemical differences: "'Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each one is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars," said Xing, postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study, which was reported in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"Every interstellar comet so far has been a surprise," added Xing. The successful observation highlights the capability of the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory. Operating above the atmosphere, its modest telescope achieves the sensitivity for these specific wavelengths that would require a much larger ground-based instrument, enabling scientists to rapidly capture crucial data before the fast-moving celestial object faded from view.

The detection of water in 3I/ATLAS confirms that the essential chemical ingredients for life are not unique to our corner of the galaxy. As astronomers continue to study these interstellar visitors, each one offers a new clue to the diversity of planet-forming environments around distant stars.

More on Starlust

Scientist explains the stripe in the new image of 3I/ATLAS from NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover

Scientists rush to coordinate spacecraft as massive comet 3I/ATLAS approaches Mars