New Cassini data suggest Saturn’s rings are thicker than they appear

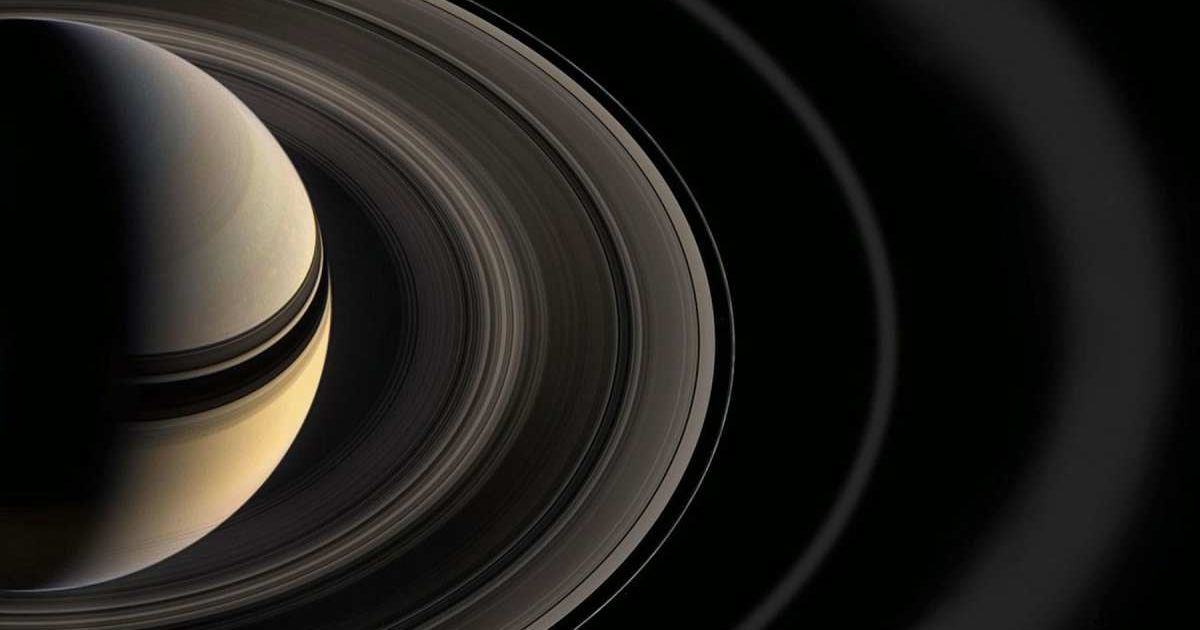

New data from the Cassini spacecraft reveal that Saturn's rings are not just the flat, thin disks they appear to be. Instead, they are shrouded in a massive, invisible "halo" of dust that extends far above and below the main ring plane. The findings were published in The Planetary Science Journal, which originated with the Cassini probe's "Grand Finale" orbits in 2017.

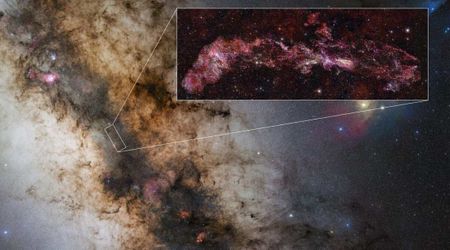

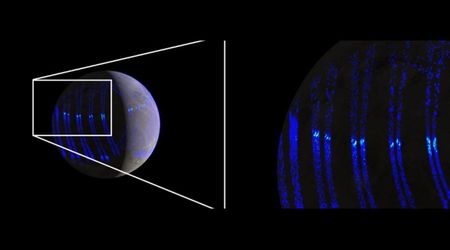

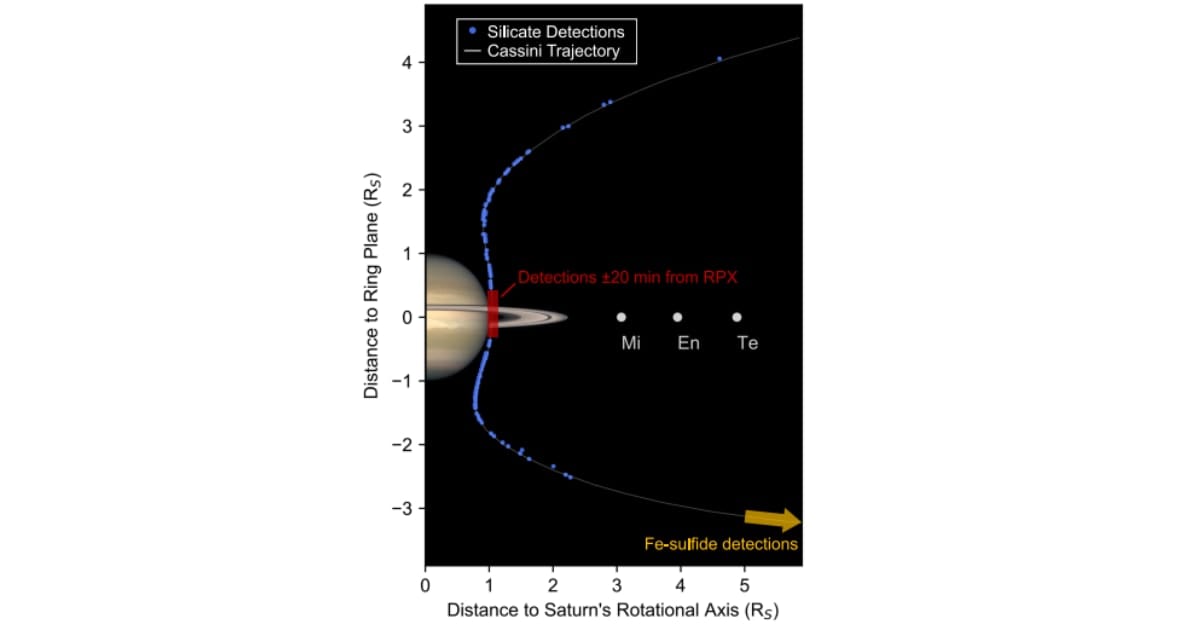

In the months leading up to its intentional plunge into Saturn's atmosphere, the spacecraft dove between the planet and its rings, capturing 1,690 dust samples using its Cosmic Dust Analyzer, per Phys.org. Scientists found that silicate-particled dust was floating at distances as far as three times the radius of Saturn above the ring plane. But despite their distance, grains that far out were made up of the same chemical composition as the material within the main rings. Both the near and far dust samples were rich in magnesium and calcium, yet noticeably low in iron. The "striking" similarity ultimately led scientists to believe that the dust isn't from deep space, but is actually material being kicked off the rings themselves.

To learn how these particles could have traveled so far, the team ran computer simulations. They found that tiny micrometeoroids, essentially space pebbles, often slam into Saturn's rings. These high-speed impacts form "vapor plumes" condensing into microscopic dust grains. If these grains are smaller than 20 nanometers and are ejected faster than 25 kilometers per second, they can be flung high into the space surrounding the planet. The majority of this dust, of course, eventually settles back into the rings or burns up in Saturn’s atmosphere, but enough remains in orbit to make a permanent, diffuse halo.

The study dismissed the idea that this dust was simply passing through the neighborhood. If particles came from outside the Saturnian system, their chemical makeup would appear far different from that of the rings. This finding proves that planetary rings are more dynamic than previously believed. The evidence has also left scientists wondering if other ringed planets, such as Jupiter and Uranus, also have these invisible dust halos created by constant meteoroid bombardment.

This discovery adds a fresh layer of mystery for stargazers looking at the "Jewel of the Solar System." Though this newly discovered dust halo is invisible to the eye, Saturn remains a premier target for amateur astronomers. Saturn presently holds the record for the most moons in our solar system, with a total of 146 known natural satellites. While most are small or hidden, seven of these moons are bright enough to be seen from Earth with a standard backyard telescope. The largest of the group, Titan, is also the easiest to spot and can often be seen as a tiny, bright point of light near the planet.

For those seeking to spot the bright planet, the best time is during its "opposition." This describes when Saturn is on the opposite side of the Sun relative to Earth. At opposition, it shines at its brightest and can be seen all through the night, rising in the sunset and setting in the morning.

More on Starlust

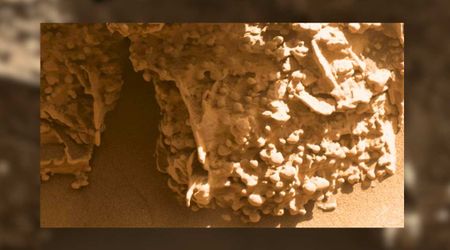

Groundbreaking data from NASA’s Cassini suggests Saturn's icy moon could support life

Organic compounds found on Enceladus suggest Saturn's moon may support alien life