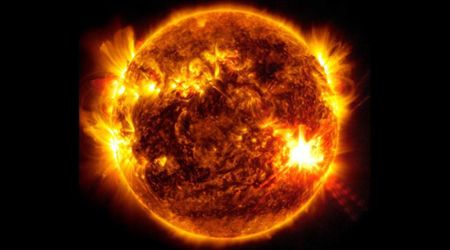

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe unveils the closest-ever images to the Sun, taken just 3.8 million miles away

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has released unprecedented images captured from within the Sun's atmosphere, marking the closest views ever recorded. These stunning visuals, acquired during a record-setting flyby in late 2024, are providing scientists with critical insights into space weather events that can impact Earth, according to NASA.

This is the view from WITHIN the Sun’s atmosphere! ☀️👀🛰️

— NASA Sun & Space (@NASASun) July 10, 2025

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe just released imagery from its closest-ever flyby of the Sun, revealing details in the solar atmosphere that scientists will be studying for years.

More: https://t.co/ZDyJ1ReiWC pic.twitter.com/fuEVAy55mk

“Parker Solar Probe has once again transported us into the dynamic atmosphere of our closest star,” stated Nicky Fox, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. “We are witnessing where space weather threats to Earth begin, with our eyes, not just with models. This new data will help us vastly improve our space weather predictions to ensure the safety of our astronauts and the protection of our technology here on Earth and throughout the solar system.”

The probe's journey, which brought it within 3.8 million miles of the solar surface on December 24, 2024, utilized the Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR) instrument to capture the intricate details of the Sun's outer atmosphere, or corona, and the solar wind. The new WISPR offers a detailed look at the heliospheric current sheet, where the Sun's magnetic field direction shifts. Furthermore, the probe captured high-resolution collisions of multiple coronal mass ejections (CMEs), large bursts of charged particles that significantly influence space weather.

Today, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will complete another close encounter with the Sun! 🚀☀️

— NASA Sun & Space (@NASASun) March 22, 2025

The close approach will equal its record-setting flyby on Dec. 24, 2024, in both speed and distance from the Sun.

More: https://t.co/u6MIDsgZXS pic.twitter.com/QXi2jiYFmE

“In these images, we’re seeing the CMEs basically piling up on top of one another,” stated Angelos Vourlidas, WISPR instrument scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Understanding how CMEs merge is vital, as these collisions can alter their trajectories and amplify their effects, posing greater risks to satellites and ground-based technology. The Parker Solar Probe's close proximity is crucial for preparing for such events.

This mission is building on the legacy of Eugene Parker, who first theorized the solar wind in 1958. Earlier findings from the probe revealed that the solar wind exhibits erratic "zig-zagging" magnetic fields or switchbacks near the Sun. Scientists have now pinpointed the origins of these switchbacks and announced that they contribute to powering the fast solar wind, helping to resolve a 50-year-old mystery. The probe continues its work to understand the generation of the slower solar wind and how these particles escape the Sun's immense gravity, as mentioned on NASA's official site.

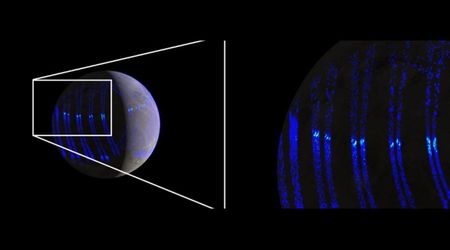

The probe is also shedding light on the slow solar wind, which is denser and more variable than its faster counterpart. Its interaction with the fast solar wind can sometimes generate solar storm conditions comparable to those caused by CMEs. Prior to the Parker Solar Probe, distant observations suggested two types of slow solar wind existed, distinguished by their magnetic field variations: Alfvénic, which features small-scale switchbacks, and non-Alfvénic, which lacks these variations. The Parker Solar Probe has now confirmed the existence of both types and is helping scientists differentiate their origins. It's theorized that non-Alfvénic wind may emerge from helmet streamers (large loops connecting active regions where particles escape), while Alfvénic wind might have originated near coronal holes or dark, cooler regions in the corona.

With its current orbit bringing it so close to the Sun, the Parker Solar Probe will continue to gather crucial data in upcoming passes, including its next on September 15, 2025, to further confirm the slow solar wind's origins. “We don’t have a final consensus yet, but we have a whole lot of new, intriguing data,” noted Adam Szabo, Parker Solar Probe mission scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.